Claude Harmon: ‘Think of a swing like this: If the house is poorly built, it’ll crumble’

Last updated:

Claude Harmon III, the man who fine-tunes the swings of Dustin Johnson and Brooks Koepka, has some advice to improve your driving

As a third-generation coach, Claude Harmon has had a hard time living up to his family’s name. Much has been made of his dad coaching Tiger for 11 years and taking him to World No.1, but less has been said about Claude’s grandfather winning The Masters in 1948. Throw in his three uncles – Dick, Billy and Craig – who coached or caddied on the PGA Tour, and you can understand why the Harmon name is so revered in golfing circles.

Related: US PGA Championship 2020 Preview

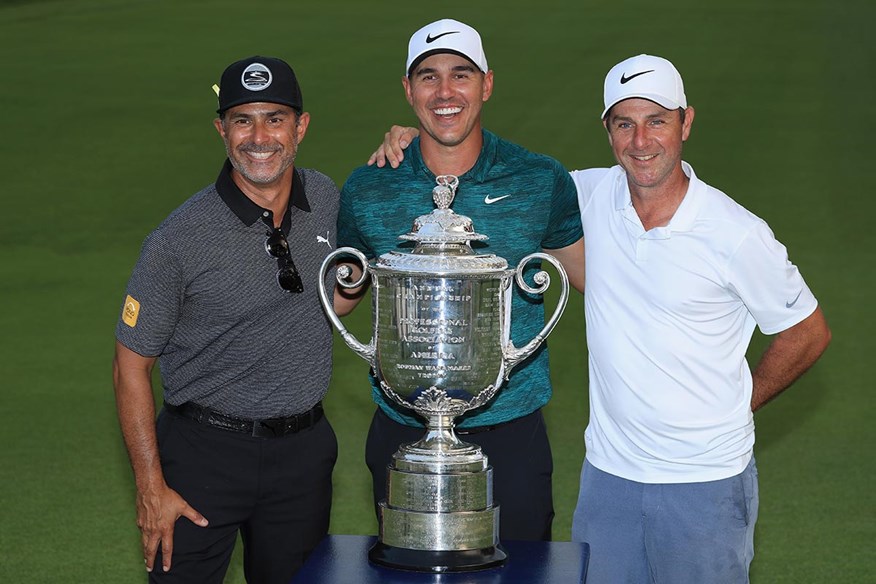

A coaching empire has been forged off the back of their success, and Claude, like his father, has now guided several players to the pinnacle of the game – including current World No.1 Brooks Koepka and the man he replaced at the top, Dustin Johnson. Ironically, his big break came at the Butch Harmon Learning Centre, under the guise of director of instruction at Floridian National, where he started working with Ernie Els and coached him to his fourth Major title – and first in eight years – at the 2012 Open.

The victories have kept flowing ever since, first with DJ and, more recently, with Koepka, including this year’s back-to-back Majors in the USA. Their success, he admits, owes a lot to their strength off their tee, which was ranked among the best on the PGA Tour last season.

Recognising as much, we flew halfway across the world to spend a day with Claude, in the hope that we could debunk some of the myths behind driving and uncover the secrets behind DJ and Koepka’s success. But first, we couldn’t resist asking about his dad’s working relationship with Tiger and what it was really like growing up in the Harmon household… (Jump to drills)

I was always around golf from an early age.

I didn’t really have a choice with my family. My grandfather won the Masters in the ’40s; and then my dad and my three uncles all went into coaching, and worked with people like Greg Norman, Curtis Strange, Lanny Wadkins and Ben Crenshaw. I think I was on Tour two weeks after I was born because my dad was still playing then. My uncle Billy used to be a caddie on Tour and Bill Haas was named after him. My uncle Billy’s first child was then named after Jay Haas, so you could say we’ve left a mark on the game.

Related: Ricky Elliott – Life as Brooks Koepka’s caddie

I didn’t play golf growing up, but I remember watching my dad, uncles and grandfather give lessons.

I spent a summer helping out, watching my dad teach, when I was about 16 or 17. That was my first introduction. I went to the Masters for the first time in 1987 when my grandfather was still alive. That gave me an indication as to what my family was about and what they did. I had breakfast every morning in the champions’ locker room with my grandfather and people like Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer, Gene Sarazen, Seve… the real greats.

I actually videoed the first-ever lesson my dad gave Tiger.

That was on August 23, 1993. At that time, my dad was working with Greg Norman, who had just gone back to World No.1 and won The Open at Royal St George’s, but I just remember how amazed he was. Neither of us had ever seen anyone swing a golf club as fast as Tiger.

Tiger had regular shoes on and we had to give him a glove as well.

But what stood out was how honest and open he was about his ability. My dad asked him about his philosophy and how he played, and he said: “Listen, I just hit it as hard as I can on every shot and go and find it. I don’t really know where it’s going to go every time, but I’m just so much longer than everyone I play with.” When my dad asked him to do something he couldn’t do, Tiger would admit that, but would say, “if you teach me how to do that, I’ll try.” For a 16-year-old to be that honest about his own ability was unique. Most young juniors want to tell you how good they are, but Tiger was different.

RELATED: Best Golf Podcasts

He used to stay at our house sometimes.

I would pick him up from the airport and buy him lunch because he didn’t have any money. It was my job to wake him up. I would then go take a shower, and wake him up again! This was before he had the laser surgery, so he had really thick, Urkel-type glasses. He’d always be fumbling around trying to find them. But that was when Tiger was just a normal, 16-year-old kid. I mean, you can’t become who he’s become and have any sort of life. There’s a point when fame changes that.

As Tiger got older, the circle around him closed.

I remember how going out to dinner with him in 2000 was just a grind because you couldn’t get a moment’s peace. I’ve always said Tiger feels most comfortable when he’s inside the ropes. That’s when no one can bother him and the only part of his life when he’s fully in control.

The first player I worked with on my own was Trevor Immelman.

At the time I was helping Adam Scott, but I got talking to Trevor in the gym in Dubai. We ended up going out to dinner and two weeks later I started working with him. That was at Paris National in 2002 and he shot the course record in the first round. He had a chance to win, but finished second to Malcolm MacKenzie. Within a year, Trevor won two tournaments, and broke inside the world’s top 50.

When you’re lucky enough to have a father like mine and your dad is Butch Harmon, it’s hard to **** up!

He was always there, but to have a player seek me out, on my own, was huge for me. I purposely didn’t talk to my dad about what I was working on with Trevor for about a year. I wanted to make sure everything we did was based on my own ideas. We had a great run, but in the end my kind of self-worth and success were wrapped up in Trevor’s success. I remember standing on the range at the World Cup of Golf in 2004 and quitting because I didn’t like how I had become.

I didn’t work with Tour pros from 2004 until 2010.

I just became really disillusioned with the pressure and travel. When you’re around these guys, it’s a very intense relationship. Trevor was a perfectionist, so it was tough. I only started feeling good about myself when Trevor was playing good, and would be down on myself when things weren’t going well. Golf was my only identity and I lost who I was. When I realised that, I didn’t want to do it anymore.

Related: Pete Cowen saves you shots

I got away from tour life and opened a golf school in Dubai in 2008.

I was there for three years and it helped me rediscover the joy of teaching. It was also a really good learning curve, working with amateur golfers. I almost quadrupled the size of the golf school, which just so happened to be at The Els Cub. My dad had been working with Ernie, but they went their separate ways and then Ernie asked me to watch him hit some balls at a Race to Dubai tournament. He played well and, off the back of that, I became his full-time coach. It was around the same time I moved back to the US to start at Floridian, so it worked well in that sense. Ernie was really down in the doldrums and had reached the time in his career when he was wondering how long he could keep playing golf for, so to help him win a fourth Major just a year later was pretty amazing. To then follow that success with DJ and Brooks, who’ve also won Majors, has been really special.

For Brooks to do what he’s done over this year, and even the last two years, has been amazing.

Given how bad his injury was, in February this year we literally didn’t know if he would ever be able to play golf again. We didn’t know if we were going to have to change his grip, change his golf swing or change everything. For golfers, necks, backs and wrists are what breaking your leg or blowing out your ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) is to footballers. You just don’t know if you’re able to come back. For somebody like Brooks, whose game is based on speed and power, to have an injury to your left wrist is career threatening and catastrophic. For him to come back, win three times including two Majors, be named Player of the Year and get to No.1 in the world is just crazy. It just shows how good he is. I think the sky is the limit for him.

Brooks and DJ both want to hit fades, so the work we do is very similar.

In Brooks’ case, we try to keep the clubhead in front of his body, because he has a tendency to pull it too far inside on the way back. In the downswing, we try to keep the clubhead outside his hands so he can release the club freely and hit a power fade off the tee.

There are parallels between what I might coach a Tour pro and a mid-to-high handicapper.

With Brooks, we got to the US PGA and he felt like he’d hit it as well as he’d ever done the week before at the WGC at Firestone. On the Tuesday, we were walking around and he said, “I don’t need a lot this week. I’m swinging really good. Just make sure my lines are good,” meaning his basics. That’s basically what we worked on that week. He went on to win his second Major of the year and my job was purely down to making sure his grip, stance, posture and alignment were good.

Very few golfers pay enough attention to the set-up.

It really takes no athletic ability – or even golf ability – to get into a good set-up. But most golfers are in such a bad position to begin with that they really struggle as the golf swing gets into motion. If you look at the great drivers of a golf ball – people like DJ, Brooks, Rory and Jason Day – they look like they were born with a driver in their hands. It’s very difficult to hit consistent golf shots if the fundamentals aren’t right. Think of it this way: If the house is poorly built, it will crumble.

In my experience, most golfers do slice the ball, and try to fix it with an anti-slice set-up.

They’ve probably read that you need a closed stance to hit a draw, but because their ball position is too far forward, their feet are then pointing right of the target and their shoulders are pointing to the left. That encourages an out-to-in swing, which then causes a slice.

Related: Most forgiving drivers 2020

The average golfer has an iron swing with their driver, and a driver swing with their irons.

Meaning, when they hit irons, they don’t take divots because their angle of attack is up and they are trying to help the ball into the air. If you go to most golf clubs in the UK, look at the tee box on a par 5 and you will see divot marks. Go to a 625-yard par 5 at a PGA Tour event, and there will be no divots on the tee. The average golfer tends to hit down, get steep with their driver and sky it. What you really want is to swap your driver swing for your iron swing, where you’re hitting up on it and not taking a divot.

When you go out on the golf course, play golf, not golf swing.

Only work on your swing when you’re on the driving range. Most people go out to play and try stuff, as opposed to allowing for their shot shape and working with what they’ve got. So, if you do suffer from a slice, aim down the left side of the fairway to give yourself more room.

If you’re suffering from a two-way miss off the tee, get on the driving range, work on hitting one shape, and try to feel comfortable doing it.

Whether it’s a slice, hook, draw or fade, you’ve got to be able to do something consistently. If you have to play a 15 or 20-yard slice or hook, stand up and do it so you know where to aim when you’re on the golf course.

Most of the technology we use, like launch monitors and 3D, is all range based.

That’s why I’m such a big fan of Cobra Connect. Having sensors in your golf club takes away that guesswork and tells you the shapes you’re hitting, how far you’re hitting and where your miss pattern tends to be. A lot of people hit it great on the range, but that doesn’t really translate on the course. Cobra Connect is the first piece of technology which can be used when you’re playing the game, not when you’re practising. As a coach, I’m far more worried about what players are doing when they play, not what they are doing in their practice.

If you’re a 15 handicapper, you’re crazy if you don’t have Cobra Connect in your golf clubs.

I don’t work with any juniors who don’t have it. It’s just a prerequisite, so I can see what they are doing when they play. If a player is trying to get better, it’s an easy way to track your progress. If you’ve got a smartphone, download the Arccos Driver app and it will tell you where you can improve and what you need to improve. You might think you’re a bad driver, but the technology could say otherwise and highlight that you’ve got a bad iron game or short game. That makes your practice sessions far more valuable because most peoplepractise their strengths, but ignore their weaknesses.

Related: Best Drivers for Beginners and High Handicappers

Claude Harmon: Drills

Drill No.1: DOMINATE YOUR DRIVER

The slice is easily one of the most destructive shots in golf, and the problems nearly always start at set-up. Most golfers think they need to angle their shoulders left to hit a draw, when actually they need to do the opposite. They also tend to get left-side dominant, thinking that it will help to release the club more, when actually all they are doing is limiting their shoulder turn and promoting a steep angle of attack.

For some reason, most golfers always set up with the ball position too far forward in their stance. This then sets the shoulders open at address, which encourages a slice. The optimum position is in line with the left heel – pop an alignment stick or a club on the ground to make sure.

To straighten your ball flight and achieve a centred strike, you need to set up in straight lines – so the feet, hips and shoulders point in the same direction. When hitting a driver, the weight should favour the right side more – 60/40 – and the right shoulder (for right-handers) should tilt down slightly, which gets the club swinging on the up into impact.

TRY THIS: If you struggle to get through the golf ball and have some rotational issues in the hip, try flaring your left foot out. If you find there’s a restriction in your backswing as well, flaring the right foot out can also be beneficial.

DRILL No.2: CURE YOUR SLICE

Like Brooks, the average golfer takes the club too far inside on the way back, and then comes over the top into the downswing. Most problems I see stem from an incorrect weight transfer, which starts in the backswing and with the weight favouring the left side. As they transition into the downswing, their brain tells them at the last minute to swing left, and the more they do so, the more the weight shifts to the back leg and causes a weak slice. Practising the two moves below will help to solve both problems.

1. THE TAKEAWAY

To keep the club on plane, practise taking the club back straighter, so it stays in line with your feet. Try pausing at this point – just like Rickie Fowler does – to make sure you’re not rolling the wrists back and taking the club massively on the inside.

2. THE DOWNSWING

Make a conscious effort to move your weight on to your front foot as you begin your downswing. This will drop your arms to the inside, allow the body to rotate fully and keep the clubhead behind your hands into impact. That one move is key to unlocking power.

DRILL NO.3: SAY GOODBYE TO THE REVERSE PIVOT

The power Brooks and DJ generate comes from loading the backswing, or coiling into their right side. You can’t unwind if you don’t wind up. Most golfers stay static and never make any kind of turn. This drill encourages dynamic movement and stops a reverse pivot.

Standing with your feet close together, step back with your trail leg as you take your backswing. With your weight planted in your right instep, the transition into the downswing will naturally engage the core and drive that weight towards the target, unloading all the power that you’ve stored.

DRILL NO.4: ADD EXTRA OOMPH TO YOUR SWING

This is another easy drill which will add some extra speed to your swing and help you gain a few extra yards. You may have seen videos of Padraig Harrington trying something similar on the range; I liken it to Happy Gilmore because you’re basically stepping into the shot.

Again, you start with your feet close together, but this time take a step forward as the arms take the club back. Doing so creates some separation between your backswing and downswing, and makes it easier to feel how the weight shifts during the swing. That sensation is key to getting the whole body swinging the club, not just the arms.

DRILL NO.5: SWING WITH CONTROL

The single most important thing I work on with players is contact. I don’t care whether they are hitting a fade or draw.

The average golfer is obsessed with the direction the ball is going, and uninterested in contact. But if your path is out-to-in and you hit it solid, you will hit a fade. Whereas, if your path is out-to-in and the contact is bad, you will hit a weak, pop-up slice. The easiest way to improve is to focus on the quality of strike first, and the direction second.

Understanding the fundamentals and what makes the golf ball launch with a driver is key, which is why making a series of waist-high back, and waist-high through swings is so beneficial. By stripping the golf swing back, you’ll quickly learn what works and what doesn’t, and find it easier to hit the centre of the clubface when you graduate back into a full swing.

Imagine a clockface with your head at 12 o’clock and your hands at six. As you swing back, stop at nine o’clock, swing down and finish the follow through at three o’clock.

TRY THIS: If you tend to hit down on your driver and spin it a lot, try teeing it higher so you hit up on the ball. It may sound counter-intuitive, but it works.