How Margaret Abbott won gold in golf at the Paris 1900 Olympics… and never realized

Last updated:

Margaret Abbott’s unknown glory is a crazy story highlighting just how different the Olympics used to be…

Margaret Abbott died in Greenwich, Connecticut shortly before her 77th birthday in June 1955. It was, naturally, a very sad day but the mourners were able to celebrate the fact that their relative and friend had lived an unusually rich, varied, and well-travelled life.

Abbott was the daughter of the American novelist and literary editor Mary Abbott and her husband who was a wealthy merchant. Although born in Kolkata, India in 1878, when the city was still at the heart of the British Raj, the premature death of Abbott’s father shortly after her birth prompted the family to return to the United States and settle in Chicago, Illinois.

Twenty years later, on the cusp of the 20th century, Margaret and her mother travelled to Paris where Mary wrote ‘A Woman’s Paris: A Handbook of Every-Day Living in the French Capital’ and Margaret studied art alongside the celebrated Edgar Degas and Auguste Rodin.

On returning to Chicago, Margaret married the widely-syndicated humorist and writer Finley Peter Dunne, and their son Phillip was a successful Hollywood screenwriter and producer, best known in the 1940s for ‘How Green Was My Valley’ and in the 1960s for ‘The Agony and the Ecstasy’.

Margaret’s was undoubtedly a remarkable life, one in which she encountered great artists, travelled the world, and enjoyed watching her family thrive in their chosen careers, and yet when she died she was blissfully unaware of the most extraordinary triumph of her own.

Because Margaret Abbott was not only the first American woman to win an Olympic event or the first woman to win an Olympic golf competition. Margaret Abbott also scaled these sporting heights and never, ever knew it.

The Olympics used to be very different

It sounds a little absurd that a golfer could win the greatest prize in sport and remain clueless, but, after Baron Pierre de Coubertin’s revival of the Olympic spirit in 1896, the early Games were more than a little chaotic and, in any case, sporting competitions of the time were also considerably different to today’s.

In fact, the men’s golf competition at the Paris Games of 1900 reveals many of those contrasts. The winner Charles Sands, for example, was more of a tennis player than a golfer while third place went to the Scottish rugby international David Robertson. If multi-sport athletes was one trend among participants, the other was wealthy or aristocratic enthusiasts.

That eclectic men’s field also included Frederick Winslow Taylor (an American mechanical engineer with a passion for industrial efficiency and one of the world’s first-ever management consultants), Albert Bond Lambert (President of the Lambert Pharmacal Company and an aviation pioneer in the US) and Count Alexandros Merkati (a Greek Royal Court Chamberlain).

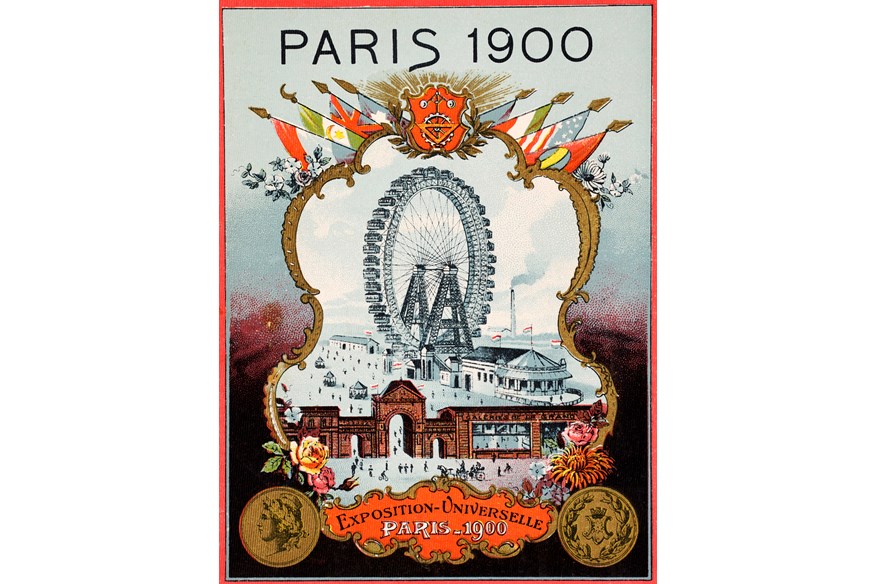

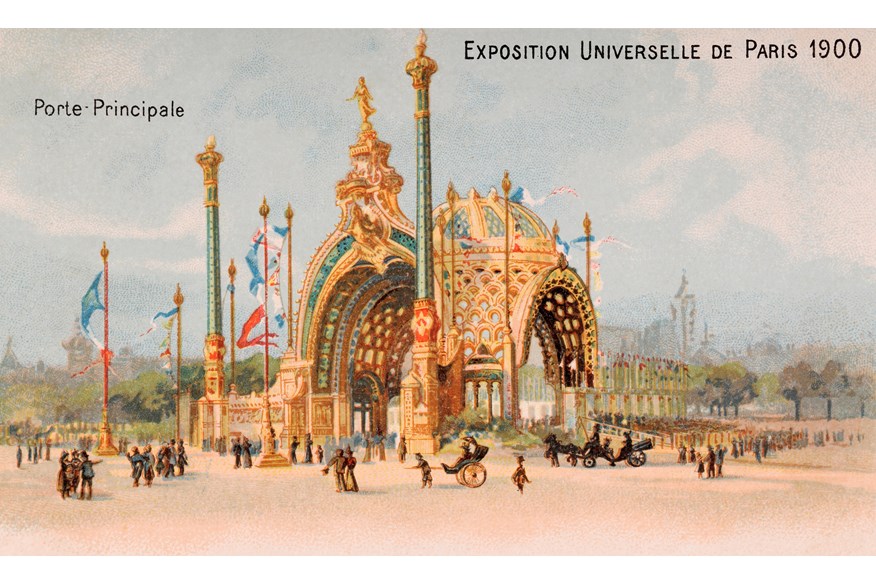

Of the chaos, it is essential to understand that the Olympics of 1900 was stretched across the calendar from May to October and that it coincided with the Paris Exposition (also known as the World Fair). Many events that summer were assumed to be part of the Exposition when actually in the Olympics, and vice versa. Yet other events, including pigeon racing and firefighting, were unofficial Olympic events.

There were also many more straightforward and self-inflicted problems. The swimming was contested in the River Seine which was as fast-flowing and dirty then as it is now. The athletics venue was among the gardens of the Bois de Boulogne which meant the track events were run on a bumpy field and the throwing events were impeded by trees which locals refused to cut down or even trim (javelins got stuck in those trees, while the discus arena was too short and spectators were in the firing line).

De Coubertin himself later said (and you can imagine him doing so with his head in his hands): “It is a miracle the Olympic movement survived these Games.”

Survive it did, but the women’s event lasted just one Games before its return in 2016 and that might have something to do with the bizarre nature of that inaugural competition.

Which takes us back to the Abbotts ladies, enjoying their time in the City of Light like characters out of a novel by Henry James or Edith Wharton. They spotted a newspaper notice of a golf event called the ‘Prix de la ville de Compiègne’ or, in English, ‘The Prize of the town of Compiègne’ and, being keen golfers, in addition to budding artists and socialites, entered.

The nine-hole event took place at Compiègne GC in early October, a day after the men’s event was completed, and reports suggest that there were large and enthusiastic galleries. Grainy photographs of the action show caddies in raffish hats (was an artist friend persuaded to carry a bag?) and competitors in enormous headgear, intricate blouses, and wide skirts.

Mary completed the course in 65 strokes to tie the Baroness Lucile de Fain in seventh while Count Merkati’s mother-in-law Abigail Pratt (later to become Daria, Princess Karageorgevich) finished third on 53 shots.

The American Pauline Whittier, who was herself studying in the Swiss resort of St Moritz, broke 50 by one to take second, but she couldn’t match the 47 carded by Margaret whose prize hints at one of the many reasons she remained in ignorance of her feat.

Olympic winners didn’t always receive medals

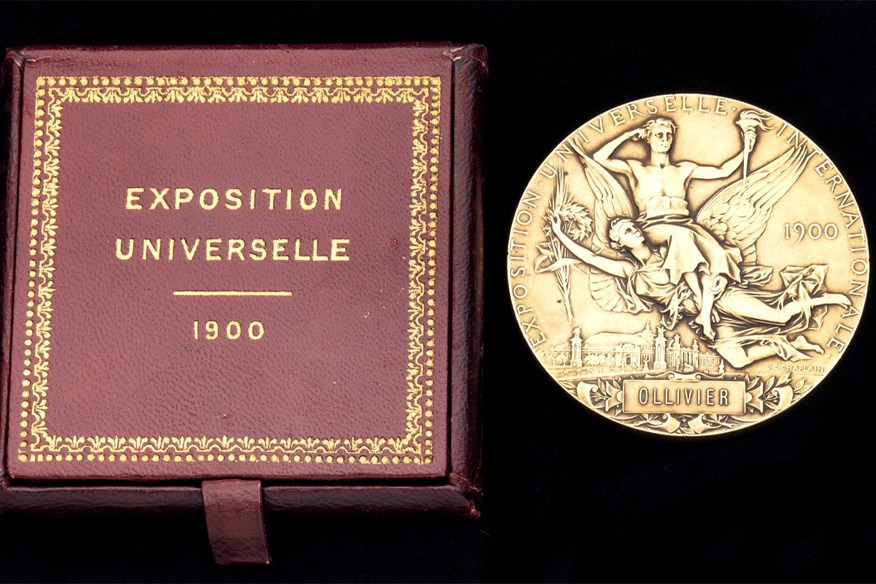

At the 1896 Games, winners received a silver medal and olive branch with the runner-up gifted a copper or bronze medal and laurel branch. It was only at the St. Louis Games of 1904 that the gold, silver and bronze medal tradition began.

At the Paris Games, in line with all the other confusion, some champions received rectangular medals but others were awarded all manner of cups and trophies. Margaret was handed a porcelain bowl with a gold mounting and pottered back to Paris to continue her art.

The Abbott ladies would not only never know what Margaret had won, they would also never know that they were, and remain, the only mother and daughter competitors in the same Olympic event.

It was only in the 1980s that Paula Welch, a professor at the University of Florida, revealed the astounding truth to relatives of Abbott who knew of the win but explained that Margaret herself had described it as “the golf championship of Paris”.

Golf dropped from the Olympics

Abbott could not have defended her title in St. Louis, even if she had known she had a title to defend because the women’s event was dropped and a men’s team event added.

The 1904 competitions had their own absurdity, not least a very American-heavy and international-light nature. No less than 72 of the 75 golfers in the individual event were Americans (the other three were Canadians, including the gold medal winner George Lyon). The team event was even more preposterous: all three teams were American.

Lyon travelled to London for the 1908 Games but golf was dropped when English and Scottish golfers couldn’t decide who should represent the British team. The sport had another go at Olympic competition in Antwerp in 1920 but lack of entries saw it cancelled again.

104 years later the New Zealand Olympic Committee told Ladies European Tour performer Momoka Kobori that although she had qualified for the Paris Games they would not be sending her to Paris. She offered to pay her own way and they still said no.

Nelly Korda going for gold (again)

Nelly Korda will be there, however, to defend the gold she won in Tokyo and, unlike her compatriot Abbott, she was well aware of what her victory has meant to herself and others.

“Whenever I bring it out around my friends and family they’re always amazed and really moved by it,” she said at the Evian Championship. “Just seeing that impact on people has been really cool.”

She also relished the chance to celebrate her success.

“When I stood on that podium there was a complete rush of emotion like I’ve never felt in my entire life,” she said. “Seeing my country’s flag go up – that’s when I realized that, wow, I just won an Olympic gold medal. My WHOOP (fitness tracker) said the highest heart rate I had that day was on the podium.”

And what is she most looking forward to on her return to the Olympics?

“It’s the little things,” she said. “The camaraderie between the countries and it’s really cool how everyone trades pins.”

Ah, yes. The trading of Olympic pins: the equivalent of swapping of Panini football stickers for elite-level sportsmen and sportswomen that takes place in athlete villages instead of school playgrounds.

It’s a long, long way from Margaret Abbott, her year out in Paris, and a venture to the golf course that was far, far more significant than she was ever aware of.

-

There were gold medals at the 1900 Paris Olympics, but not every winning athlete received one

There were gold medals at the 1900 Paris Olympics, but not every winning athlete received one

-

The Olympic Games were held during the Great Exposition in Paris, 1900. This contemporary illustration features a general view of the exposition including the formal entrance gates and ferris wheel.

The Olympic Games were held during the Great Exposition in Paris, 1900. This contemporary illustration features a general view of the exposition including the formal entrance gates and ferris wheel.

-

A vintage colour illustration featuring the main entrance to the Universal Exposition held in Paris which included the second modern Olympic Games, circa June 1900.

A vintage colour illustration featuring the main entrance to the Universal Exposition held in Paris which included the second modern Olympic Games, circa June 1900.