The Open 2022: The secret life of the Swilcan Burn

Last updated:

There are more formidable water hazards in golf, but none can claim to be as famous as the stream that crosses the 1st and 18th fairways of the Old Course at St Andrews.

Today’s Golfer’s 2022 Major coverage is brought to you in association with TaylorMade.

The great golf writer Bernard Darwin may have described the Swilcan Burn as “a paltry little streamlet” and even “an inglorious little thing”, but because it’s the first and final major obstacle on the Old Course, there are few hazards anywhere in the world with such a rich history.

There are a couple of bridges over the Swilcan Burn (which, by the way, has a plethora of alternative spellings – Swilken and Swilkin being the most popular), but only one of the bridges is really known as the Swilcan Bridge.

This is the simple, Roman arch bridge in front of the 18th tee, which some say has been there for more than 700 years and was originally built so that shepherds could bring their sheep and cattle down to the beach.

“There is only one hill to climb at St Andrews,” said that famous mountaineer Colin Montgomerie, “and that’s to cross the Swilcan Bridge”.

Everyone who is anyone in golfing history has had their photograph taken on this bridge, from Young and Old Tom Morris, Harry Vardon, J.H. Taylor, Henry Cotton, Gene Sarazen and Bobby Jones to Sam Snead, Byron Nelson, Arnold Palmer, Gary Player, Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods and Rory McIlroy.

RELATED: St Andrews Old Course – hole-by-hole guide

Snead tap danced across it wearing his trademark straw fedora and Paula Creamer celebrated the fact

that the Women’s British Open was being played at St Andrews by doing a cartwheel just in front of the bridge. Palmer decided to announce his retirement from the game from this spot, as many have done, waving farewell with tears in his eyes.

The day was Friday, July 20, 1984, and it would have been a unique and unforgettable moment, except that he was back on the bridge, six years later, doing it all over again. And then, in 1995, he did it all a third time!

And, it’s not just golfers who’ve had pictures on the famous bridge, which boasts a life-size stone replica at the World Golf Hall of Fame in Florida. Bill Murray, Hugh Grant, Michael Douglas and Kevin Costner among many other A-list celebrities have posed with the R&A clubhouse and town’s skyline as a backdrop.

There used to be a YouTube video of a woman scattering the ashes of her husband under the bridge, with a moving tribute to the man who had introduced her to the game. And an old St Andrews starter, James Johnstone, actually got engaged on the bridge.

Even hen, stag, wedding and birthday parties pause and pose on it. Walker Cup, Curtis Cup, rugby and football teams giggle and smile for the iconic shot.

RELATED: Who’s playing in the 150th Open?

Before 1880, the burn meandered across the links in various haphazard channels, depending on the tides and floods of the day. Historically, it had always marked the boundary between the property of Mr Cheape of Strathtyrum and the town’s common land.

By the late 1870s, there was gossip in the town that the direction of the burn was being altered, and some suspected Mr Cheape was doing this on purpose to increase the size of his lands.

As a result, Mr J.C. Fernie (who was a member of the Royal and Ancient) took up the fight. On the night of September 9, 1879, he arrived on the Old Course with a large band of labourers and lots of spades. They dug for 12 hours to restore the Swilcan to the original course it had flowed in 1821, when Mr Cheape bought the Links.

Mr Cheape wasn’t overly impressed with Mr Fernie’s hard work. Fernie argued the burn now ran as it always used to, but sadly for him the Town Council disagreed, and Cheape won the court case. Fernie had to apologise and pay Cheape £30 in expenses. Fortunately, Cheape agreed the course of the Swilcan needn’t change again.

One hundred years ago, the burn had sloping sides and muddy banks. Spectators at The Open used to jump over it, boys would look for tadpoles in it and balls hit in there would often not be found because it was so muddy. Nowadays, the banks have concrete walls and the water is clearer. When there isn’t much water in it, it’s still possible to play out of the burn.

RELATED: Tiger’s Major wins ranked and rated

As you stand on the famous 1st tee, knees a-jangling with nerves, the bridge is the only evidence of the burn that lies surreptitiously hidden from view, ready to catch you unawares. Fred Couples didn’t know it was there when he first played the Old Course and gave his caddie a dreadful earful when his opening drive found a watery grave.

Everyone remembers when Doug Sanders missed a tiddler on the 72nd green to eventually lose the 1970 Open, but few remember he was in the Swilcan Burn en route to a six on the 1st. Countless others have hit seemingly brilliant approaches to the 1st green, only for their ball to suck back into the stream.

The Swilcan will once again be in the spotlight at this year’s Open; either giving misery to players at the very start of their rounds, or allowing others to finish in glory, waving teary-eyed from its bridge.

And although there is very little which is certain in this life, I’m happy to put my house on the fact that the winner of the 150th Open Championship will have his photograph taken with the Claret Jug, standing above the most famous water feature in golf, stood proudly on the Swilcan Bridge.

Field work: Finding the source of the Swilcan Burn

Duncan Lennard attempted to track down the source of the most famous stream in golf

Finding the Swilcan Burn with your approach shot on the Old Course’s opening hole is quite easy; unfortunately, finding the source of golf’s most famous stretch of water is less so.

When TG handed me this seemingly innocent task, I jumped at the opportunity and instantly and energetically took the lazy option, getting on the phone to call people who should know. However, they didn’t. Fife Council and other local water services had no idea, and Gordon Moir, then the Director of Greenkeeping for the Links Trust, believed it was spring-fed but could offer no further information.

RELATED: Is the Old Course really the world’s best course – or is it overrated?

And so it was that I found myself drowning in an arable sea of foliage some three miles west of St Andrews. According to the Ordnance Survey it would be somewhere around here, in the crop fields north of Strathkinness, that I would find the burn’s first oozings.

Given the dense, eye-level crops and general aridity, it seemed a hopeless task. Yet the field began to shelve downhill, eventually forming part of an immense swale.

I headed to its low point, certain of success, but it was as dusty as the rest of the field. As I followed the swale east, the crops died back and the ground became rocky. And boggy. Some 200 yards further on, the bog formed into

a man-made drainage ditch… and here was the first visible water, trickling east at the pace of a geriatric snail.

I’d like to tell you the source of the Swilcan Burn was a sudden streak of silver, arcing forth into a grotto framed by a little rainbow. Instead, it seems more likely the Swilcan Burn owes its genesis to rainwater run-off, gathering and swelling at the base of a huge swale. In a game that has its share of heroes emerging from humble beginnings, the Swilcan Burn is one more.

READ NEXT: Ranking The Open’s courses

-

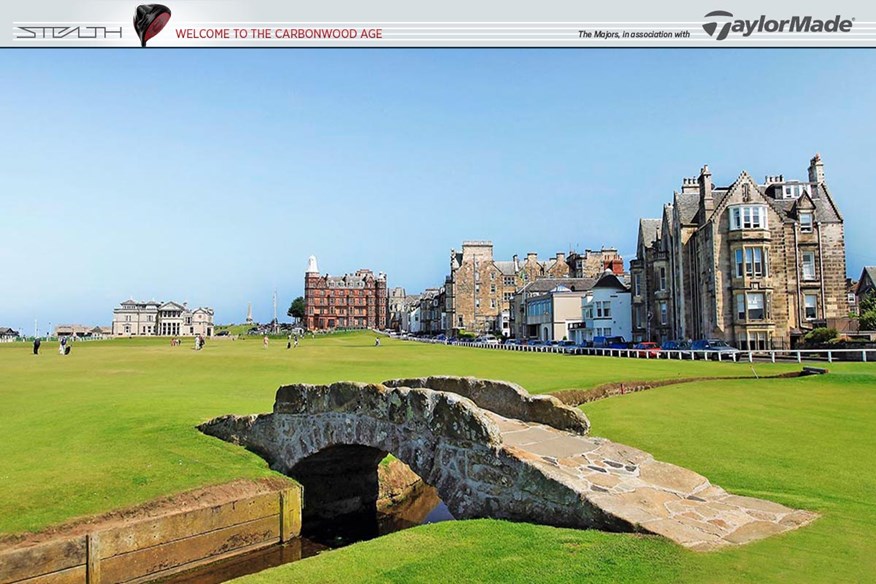

The famous Swilcan Bridge across the Swilcan Burn at St Andrews Old Course.

The famous Swilcan Bridge across the Swilcan Burn at St Andrews Old Course.

-

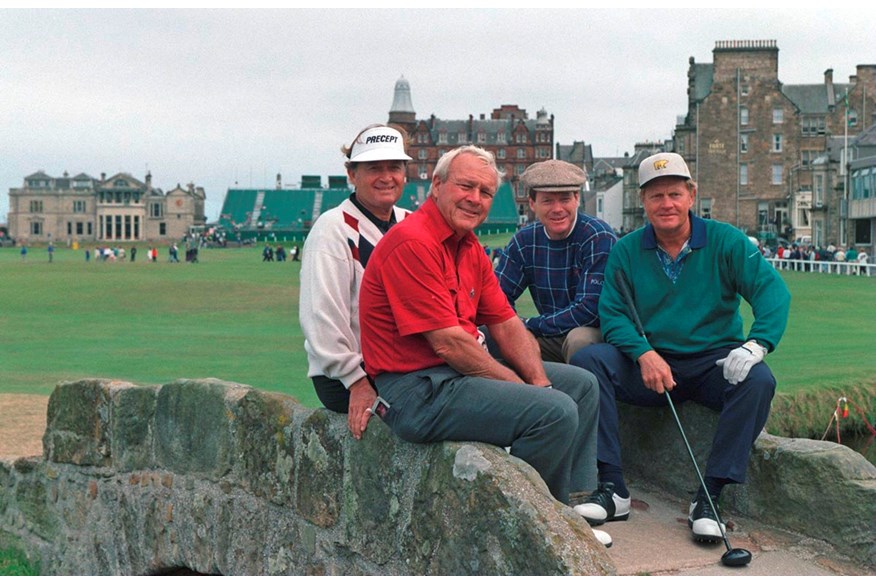

Raymond Floyd, Arnold Palmer, Tom Watson, and Jack Nicklaus pose on the Swilcan Bridge.

Raymond Floyd, Arnold Palmer, Tom Watson, and Jack Nicklaus pose on the Swilcan Bridge.

-

Jack Nicklaus waves goodbye to The Open Championship on the Swilcan Bridge in 2005.

Jack Nicklaus waves goodbye to The Open Championship on the Swilcan Bridge in 2005.

-

The Swilcan Burn and Bridge, with the Old Course Hotel in the background.

The Swilcan Burn and Bridge, with the Old Course Hotel in the background.

-

Louis Oosthuizen poses with the Claret Jug on the Swilcan Bridge after winning the 2010 Open at St Andrews.

Louis Oosthuizen poses with the Claret Jug on the Swilcan Bridge after winning the 2010 Open at St Andrews.

-

We try to track down the source of the Swilcan Burn, which crosses the 1st and 18th holes on St Andrews Old Course.

We try to track down the source of the Swilcan Burn, which crosses the 1st and 18th holes on St Andrews Old Course.