The British Open: History of the Claret Jug

Last updated:

It’s one of the most famous prizes in sport, but why does the winner of The Open Championship receive a Claret Jug? This is the story of golf’s most coveted silverware.

The Open Championship trophy, otherwise known as the Claret Jug, has had many things drunk from it; and – oddly enough – little of that has been claret.

Some argue you can tell a lot about the ‘Champion Golfer of the Year’ from what he chooses to drink from the Jug. Tiger Woods, for instance, celebrated the first of his three Open victories, in 2000, with Dom Perignon Champagne. In 1995, John Daly drank Diet Coke out of it on the night of his victory. 2002 winner Ernie Els opted for rum and blackcurrant.

And while the Jug has put up with all this imbibing with the minimum of fuss or complaint, even its placid and imperturbable nature must have been tested when Stewart Cink (Champion at Turnberry in 2009) decided to put tangy barbecue sauce in it…

This somewhat eccentric behavior took place during the Cink family’s Fourth of July Celebrations in 2010. “It made a great condiment holder,” he said. “Then I noticed that some of the sauce was still in the Jug when I was about to hand it back. A panic ensued as we scrubbed it hard to get it all out!”

The Claret Jug stands 20 inches tall and weighs approximately 5.4lb. Most Champions have kissed, hugged, and/or cradled it. Padraig Harrington, encouraged by his young son Patrick, even tried to catch ladybirds in it.

Made from sterling silver in the style of an 18th-century drinking vessel, the legendary Jug – or to give it its correct title, ‘the Golf Champion Trophy’ – remains one of the most recognizable prizes in sport.

And yet, what few realize is that the trophy, held aloft by each year’s winner, is merely a copy of the original.

It is one of the best-kept secrets in golf, and it’s not something The Royal & Ancient Golf Club like to discuss much, but they have, in fact, commissioned five Open trophies over the years. “We have the first Claret Jug, made in 1873, a replica made in 1927, and three relatively modern versions,” says Hannah Fleming, Learning & Access Curator at the R&A.

Each one is a perfect replica, right down to the tiny hyphen in the 1991 Champion Ian Baker-Finch’s name. One of the three more recent versions resides in the British Golf Museum in St Andrews. Another is at the World Golf Hall of Fame, in Florida. The third is used for traveling exhibition purposes and is taken around the world for various qualifying events.

“The new champion receives the 1927 version,” confirms Fleming. “At least that way they get to keep the same trophy that Bobby Jones, Walter Hagen, and Gene Sarazen all won. We think that is quite a good compromise.” The Champion gets to own the trophy for a year and then gets a smaller version to keep.

For years, the replica given to winners was a 60 percent version of the original. Then, a couple of years after Daly won it in 1995 (and asked if he had drunk anything from it, apart from Diet Coke on the night of his win at St Andrews, replied: “Nope, it’s so small you can hardly get anything into it”), the R&A decided to offer the winner a 90 percent replica, which is what they now receive.

Prestwick Golf Club, home to the first 12 Open Championships, also have a replica, which is seven-eighths the size of the original. It was presented to the club by the R&A in 2010, on the 150th anniversary of the first Open, but only has the names of the winners from 1872 to 1925 – Prestwick’s final Open – on it.

Why a Claret Jug?

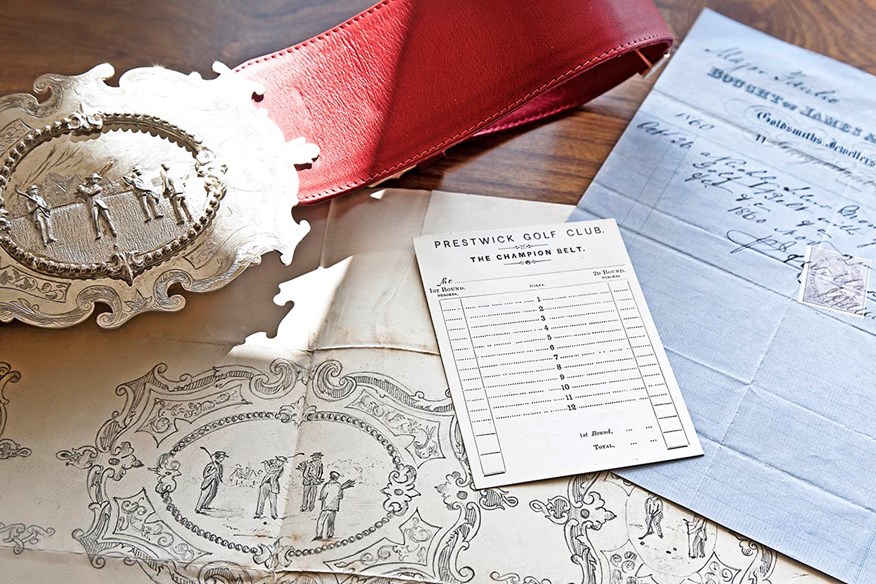

After the Challenge Belt was won outright in 1870 by Young Tom Morris (and there was no Tournament in 1871 because there was no prize), St Andrews, Musselburgh, and Prestwick golf clubs finally agreed to host The Open and agreed to donate £10 each towards the cost of a new trophy, with the R&A taking responsibility for its design.

The idea of providing another Challenge Belt (like those given out to bare-knuckle boxers of the time) was quickly dismissed. Golf was perceived as a game for gentlemen and the new trophy must reflect that. The R&A had held a ‘Grand Invitational Tournament’ in 1857, and the prize for the winning pair was an ornately decorated silver Claret Jug made by Edinburgh silversmiths Mackay, Cunningham & Co.

It seemed logical to order another for The Open and the arrival of a new trophy in 1873 secured the future of The Open Championship.

Not ready in time for the next ‘Open’ at Prestwick in October 1872, the winner, Tom Morris Jnr (for a fourth consecutive time) was compensated with an oval-shaped gold medal with the words ‘Golf Champion Trophy’ stamped on the rim, and the same three words were put on the new Open trophy when it made its first appearance a year later at St Andrews.

The first recipient of the silver Claret Jug was an illiterate local caddie named Thomas Kidd, winner at the first Open to be held at St Andrews, in 1873. And yet, his was not the first name to be engraved on it. This honor went to Tom Morris Jnr, in recognition of his victory 12 months before.

The R&A attached a ‘perpetual use’ clause to the Claret Jug in 1873, which meant that no player could win it outright (as Young Tom had done with the Belt). And so, when Jamie Anderson carved out his own slice of Open history, by winning his third consecutive Championship at St Andrews in 1879, he was somewhat unceremoniously told to hand it back after the presentation, which came as a bit of a surprise.

Controversy followed in 1890, after John Ball Jnr became the first amateur to win The Open at Prestwick. Incensed that his name had been engraved on the trophy without the prefix ‘Mr’, to distinguish him from the lowly professional winners, his home club of Royal Liverpool insisted that it be added, which it later was.

The Jug stayed in constant use for just over half a century and by the time the 1927 Open came about, the Americans Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones had established a stranglehold on the trophy, which looked like it might last a decade. This presented a headache of its own. In November 1925, the original US Amateur trophy had been turned into a lump of molten silver, after a fire at East Lake Country Club in Atlanta, where Jones had left it for safekeeping. Add to that the fact that Hagen was gaining a bit of a reputation for being slightly unreliable when it came to looking after trophies, and you can see why the R&A wanted to make a replica. (Hagen “lost” the huge Rodman Wanamaker trophy after his 1926 victory at Salisbury Golf Club in New York. Celebrating his win with friends, he paid a New York taxi cab driver to take it home for him, because he didn’t want to cut short the party. The trophy was finally recovered in 1930 in a Detroit warehouse.)

And so, after Jones’ victory at St Andrews in 1927, the R&A took the unusual (and secret) step of commissioning a replica. This was an exact copy in every way, except for the 1927 hallmark required by British law. After the 1927 Open, the original trophy was quietly retired and never used again. Today it rests in a secure glass cabinet in the front hallway of the R&A clubhouse. It is polished once a year (when it is engraved) at The Open Championship (too much polishing could damage the engraving) with silver cloth polishing – not liquid polish.

The late Alex Harvey, who was the chap entrusted to engrave it, reckons it took him up to 20 minutes to etch the name of the winner. The original trophy is on display once a year, on November 30, when the R&A clubhouse is open to the public.

Hagen won the third of his four Open titles in 1928 and was presented with the ‘new’ Claret Jug by Edward, Prince of Wales, at Royal St George’s, Sandwich. R&A records do not show whether or not the future King of England and his golfing buddy, Hagen, knew about the swap. And it wasn’t a surprise to many when Hagen returned the 1928 Claret Jug with a two-inch dent in the side, caused when he struck it with a practice swing, while drunk.

Complete nonsense

Today, the R&A suggest replacing the original Claret Jug with a later copy was simply down to five decades of “wear and tear”. “Complete nonsense!” argues golf antiquities expert Graham Rowley. “Bobby Jones had just won his second Open in succession and was challenging Walter Hagen as the dominant force in the game. Without a creditable home challenge, it must have seemed the Claret Jug would be permanently on display overseas. That’s why the R&A made the swap. They simply could not guarantee that it wouldn’t get lost or damaged.”

Hagen’s dent was certainly not the last time the Claret Jug took a battering. In 1982, Tom Watson caught the Jug flush with a 6-iron, while practice swinging at his home in Kansas City. “I heard this crashing sound as it hit the floor behind me,” he admits. “I was stunned for a moment. I picked it up and noticed the fall had bent the neck of the jug. I did feel it was repairable, so I took it downstairs to my workshop. Then, after clamping it into a vice, I somehow bent it back into place. I did a good job. Nobody knew the difference… ”

The 1996 Open Champion Tom Lehman came home one evening the following year to find his five-year-old daughter Holly had accidentally bent it about 45 degrees at the base. A rapid visit to a local silversmith helped straighten it out, but it was not the only adventure the famous trophy suffered that year. Within weeks of his victory at Royal Lytham, the Claret Jug became the subject of a police investigation when a conscientious Minneapolis tavern owner reported it stolen after he saw someone briefly visit his bar carrying it.

A 1am phone call to Lehman’s home revealed that it had been taken on a pub crawl by a member of his management company, following a charity dinner, where it had been on display. And when Martin Slumbers hands it over to ‘The Champion Golfer of the Year’, look for a bit more wear and tear. One recent Champion admitted to “bending the Claret Jug back into shape with my hands after it kept being dropped on the floor”.

MORE FROM THE OPEN

– How to watch The Open on TV

– How to get tickets to The Open

– Tee times and groups

– Where will The Open be played next?

– The incredible story of the 2003 Open

– Open Legends: Seve Ballesteros

– Rory McIlroy – ‘I’d love The Open to be at St Andrew’s every year’

– Shaun Lowry – ‘Winning The Open hasn’t changed me’

– Padraig Harrington – ‘My caddie won me my first Open‘

– Which is Tiger’s best Open win?

-

Everything you need to know about the Claret Jug, one of the most famous trophies in golf

Everything you need to know about the Claret Jug, one of the most famous trophies in golf

-

Sir Nick Faldo poses with his three replica Claret Jugs.

Sir Nick Faldo poses with his three replica Claret Jugs.

-

-

Adding the winner's name to the Claret Jug takes up to 20 minutes.

Adding the winner's name to the Claret Jug takes up to 20 minutes.

-

Thomas Kidd (left) was the first recipient of the silver Claret Jug, while Walter Hagen was the first to win the 'new' Claret Jug in 1928.

Thomas Kidd (left) was the first recipient of the silver Claret Jug, while Walter Hagen was the first to win the 'new' Claret Jug in 1928.