The inside story of Royal St George’s Golf Club

Last updated:

What is so special about Royal St George’s, host of the 149th Open Championship?

Today’s Golfer’s 2021 Major coverage is brought to you in association with TaylorMade.

A year later than expected – and despite the best efforts of a global pandemic – The Open finally arrives back at Royal St George’s where 32,000 fans will be in attendance each day. We paid a visit to a true jewel on The Open rota and Golf World’s No.1 course in England to get the inside story.

THE OPEN 2021: Royal St George’s 18-hole course guide

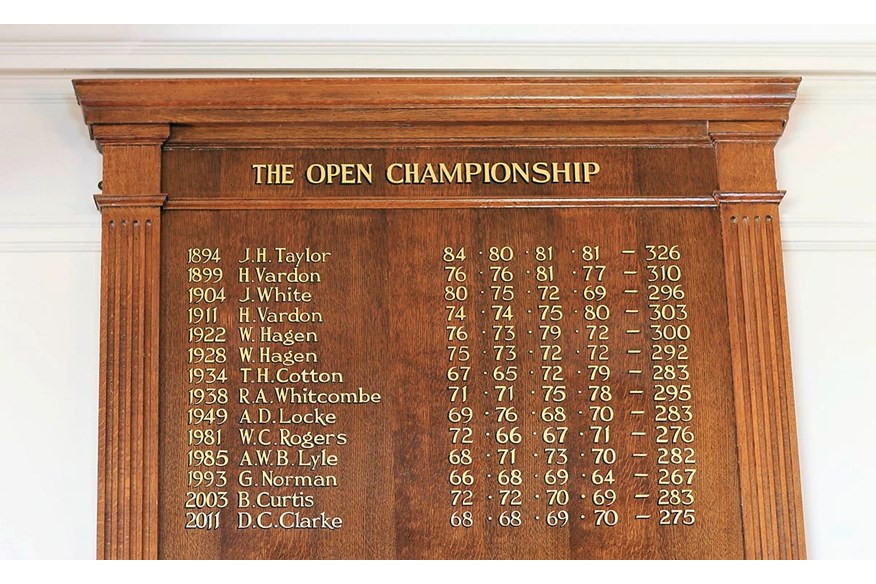

If there existed a flicker book on the history of Royal St George’s, one of those stiff-leafed affairs that you can run your thumb across the pages to see moving pictures, then the images would be captivating indeed. The club cow; a tramway taking costume-clad members to the bay for a swim; JH Taylor winning Sandwich’s first Open in 1894; a horse and cart collecting members from the station; a landmine creating a bunker on 13; tanks and artillery doing training exercises; Bobby Locke practising and winning in 1948; the arrival of the club backgammon board; Tony Jacklin getting the first televised hole-in-one (16th); unbelievable carvery lunches; Darren Clarke making Britain proud…

It would be a flicker book too big to pick up, so rich, so varied and so plentiful are the stories and legends of Sandwich’s past. A London club by the sea, the St Andrews of England and a place where time doesn’t so much stand still as sit back in the clubhouse garden admiring the herbaceous border.

What is it that makes this links golf club in Sandwich so special? It’s the tranquility, it’s the space, it’s the freshness of the sea breeze, it’s the course, it’s so many things that, with an air of inadvertent charm, Royal St George’s just seems to get right.

Speak to its members and they mention words like ‘understated’, ‘civilised’ and ‘low key’. They look around, desperate to capture the one indefinable thing that makes them so attached to this small corner of south-eastern England.

Few of them can sum it up, but all of them can feel it. It’s a club where egos are left, not so much at the door, but somewhere on the A257 from Canterbury before you angle your way through the quaint little streets of Sandwich.

If this was a club in America, there’d be a big, bold sign informing passers-by that they were on the doorstep of sporting grandeur. ‘Royal St George’s’, it’d say, ‘First English course to host The Open Championship’. Instead, there’s just a small, unpretentious sign directing eagle-eyed visitors down a country lane between two fields.

THE OPEN 2021: The 156-man field and how they qualified

Back in AD 43, there weren’t dunes here at all, just an expanse of water. By medieval times, Sandwich was the principal port of England – unbelievable when you look at it today. But, even then, sand spits and sand bars were building up as nature was busy fashioning one of the finest dune systems in the UK, creating the home of three superb links in Cinque Ports, Prince’s and Royal St George’s.

The latter was opened in 1887 and saw its first Open in 1894, won by JH Taylor, who took home the £30 first prize. But the impact on the community was little more than a nice story for the East Kent Mercury and nice pocket money for JH.

This time around it’s different. The R&A announced a £100,000 windfall from The Open Legacy Fund for the redevelopment, among other things, of the market square in the town centre, while Sandwich Station has received a £4m refit to allow more passengers to dismount from the 12-carriage trains. Thankfully, with Covid-19 restrictions gradually easing, the train station will be bustling with 32,000 fans in attendance on each of the tournament days.

While the attendance may not quite as big a number as everyone had hoped, whoever hoists the Claret Jug on July 18 will walk away with an impressive figure (and significantly more than JH Taylor) with the winner’s cheque is around just under £1.5m ($2.07m).

Kitchen to the Grave

You can have stories of Opens past (of which there’ve been 14) and of lusty blows, miraculous saves, triumphs and disasters; on a course that has also been central to the greatest golfing showdown in British fiction.

Author Ian Fleming was captain elect at St George’s at the time of his sudden death in 1964, and it was here that he chose to set the scene for his encounter between James Bond and Goldfinger.

In the film, the backdrop was Stoke Park, possibly for its more grandiose clubhouse or the fact that it was nearer London; but in the book there is no mistaking the course on which “Royal St Marks” is based.

“Bond strolled out across the five hundred yards of shaven seaside turf that led to the first tee. Goldfinger was practising on the putting green,” it says in the novel.

How many courses do you know where you cross such a wide expanse of ground? The tunnel at Wembley is not as long as this, but the feelings of excitement and trepidation are the same as you arrive on the hallowed turf of the arena itself.

At St George’s you start in the Kitchen – where most good parties do – a strange, sunken portion of ground that sits 240 yards up the first fairway from the back tee. Ahead you cross the Sahara and the Himalayas, tread the Elysian Fields, court a Maiden, squeeze between Corsets, gain passage through Suez and hope to avoid Duncan’s Hollow. That’s not to mention talk of Nancy’s Parlour, Marmalade bunkers and Kite’s Grave, the Table Mountain of a 10th green where challenges (notably Tom’s) and scorecards are regularly ruined.

Indeed, in Goldfinger, Fleming mentions a golfer by the name of Philip Scrutton, twice a Brabazon Trophy winner, who once took 14 on this hole in the Gold Bowl, a genuine club event – a moment where fiction met with non fiction.

The club’s history book is entitled A Course for Heroes and it’s evident very early and very often. The most obvious highlights include a towering bunker that used to be shored up by railway sleepers, which cuts into a huge dune known as Himalayas. It stares at you from the 4th tee like the open mouth of a shark and is famous for many moments of meltdown. One saw Reg Glading plug his ball in the top during a playoff in the quarter-finals of the English Amateur. Having climbed up, he attempted a pass at the ball, only to fall, somersaulting twice into a heap at the bottom. The ball then struck him and it was lights out, figuratively speaking.

THE OPEN 2021: How to watch all the action from Royal St George’s

It could be for that reason the fairway beyond is named Elysian Fields, which, in Greek mythology, is the land at the end of the Earth where certain favoured heroes were saved from death.

The left-curving par-4 5th is the hole where architect Martin Ebert has made his most discernible design tweak. It’s a fantastic hole for precision driving, setting up an approach that is blind over the dunes unless you land your ball in the perfect spot. To the left there used to be a fairly untidy expanse of rough and the odd bunker, but now, St George’s has its first ‘waste area’.

There are still some bunkers, but they are now set in an area of hardpan sand that is littered with tufts of brittle reed. Could this happen at St Andrews?

When you consider the link, through St George’s founder Laidlaw Purves and its Scottish inspiration, it’s not surprising that many of the names, such as Elysian Fields, can be found at both haunts. The Old Course has Hell bunker, while Sandwich used to have Hades on the right of the 8th. Ginger Beer is the 4th at the Home of Golf, while there is evidence that the 12th at St George’s has the same name. On a huge map in the locker room depicting the 1887 layout, the word Ginger Beer is etched here, possibly because a concession stand might have been set up on the bay road, just the other side of the fence from the tee.

THE OPEN 2021: 10 things you need to know about Royal St George’s

Harry Vardon, who took £50 as the Open winner here in 1899, wrote six years later: “I am constantly asked which, in my opinion, is the best course in the world. Many considerations enter into such a reckoning, but, after making it carefully, and with full knowledge that my answer is at variance with many of the best authorities in the game, I say Sandwich.”

Reach the 13th tee and you begin a loop known as Trinity, because the next three fairways form an almost perfect equilateral triangle. The 14th is Suez, with out of bounds hugging the right from tee to green and 15 has the Marmalade bunkers on the right, originally placed there to catch the Hartley brothers, Rex and Lister, who used to fade their drives.

The 16th is where Thomas Bjorn waved goodbye to his Open hopes in 2003 as his deft bunker shot from the trap on the right proved too deft and rolled back into the sand.

For two years, pot bunkers on the left edge of the 17th green were trialled, but have since been replaced by a grassy swale – something the pros will be a lot less keen on. And they might now blink when they look at 18, which has undergone a sandy revamp. Bunkers used to cross the centre, but a gap has now been created for the fearless drive.

THE OPEN 2021: The inside story of Ben Curtis’ incredible 2003 win

A strange incident took place on this final hole some years back, when a ball hit something hard in a bunker and ricocheted sideways. Bones were discovered and, after forensic analysis in Dover, the remains were confirmed as that of a large cow. St George’s has had a whole gaggle of animals through its past, including geese, sheep, horses and cows – the latter being burned in a fire. Could it have been buried on the course?

Such history, so many stories, such a culture, the like of which some people still fail to fathom. “It’s so badly signposted, I got lost trying to find it,” complained one visitor recently. “Driving into the venue, signage at the entrance was shabby,” added another. But they both miss the point.

The thing about St George’s is that not everyone ‘gets it’. Part of the absolute joy is that the signpost on the country road that leads to the clubhouse is so understated that even a passing snail might miss it. You just need to know and, when you do, you become part of the fabric. And it’s a very fine fabric, warm and cosy.

THE OPEN 2021: Champions on what it takes to win at Royal St George’s

A jacket and tie

It’s 11 o’clock in the morning and just as the club president is about to regale a story of a memorable moment at the Maiden, there’s a tapping on my shoulder. Perhaps it’s being in the presence of a man of distinction – though I think that unlikely – but the manner is discretion personified. At 11 O’clock gentlemen need to wear a jacket and the reminder isn’t unsavoury, but open and friendly. If you haven’t got a jacket borrow one of ours, he’s saying.

There doesn’t seem to be a member who doesn’t fall over themselves in singing the praises of the staff. “They always remember your name and even the names of your guests,” says one. “Nothing is ever too much trouble. They pick you up from town and drop you back,” says another.

One gentleman is also a member of a highly respected club closer to London. “Back there, they treat members better than they do guests, which I think is bananas.”

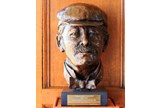

It’s impossible to overstate the understated nature of a clubhouse that manages to maintain the air of a private residence.

There is a small porch leading into a hallway and as you walk in down a corridor you’re inspected by a platoon of past captains who cast their eye over you as you head towards “The Smoking Room”.

There are no visitors’ changing rooms here because the philosophy is much the same as it would be in your own home. You wouldn’t send a guest to the outside loo if you happened to have one. “When you arrive you leave your other life behind,” they say. For half of its members, St George’s is a second club. In hard times you’d expect some of them to be giving it up, but nobody does. While there are long established rules here, they are pretty much guidelines and you can get away with a lot of things if the occasion seems right.”

If you have to ask, “Why a jacket and tie?”, you probably don’t belong. If you want a regular tee time with your usual fourball, you could be in the wrong place. And if you want your name to be emblazoned on the walls for winning the Prince of Wales Challenge Cup, then you’re not going to be in luck either. Only Open Championship winners have their names on an honours board. The members here are too modest to boast of past glories.

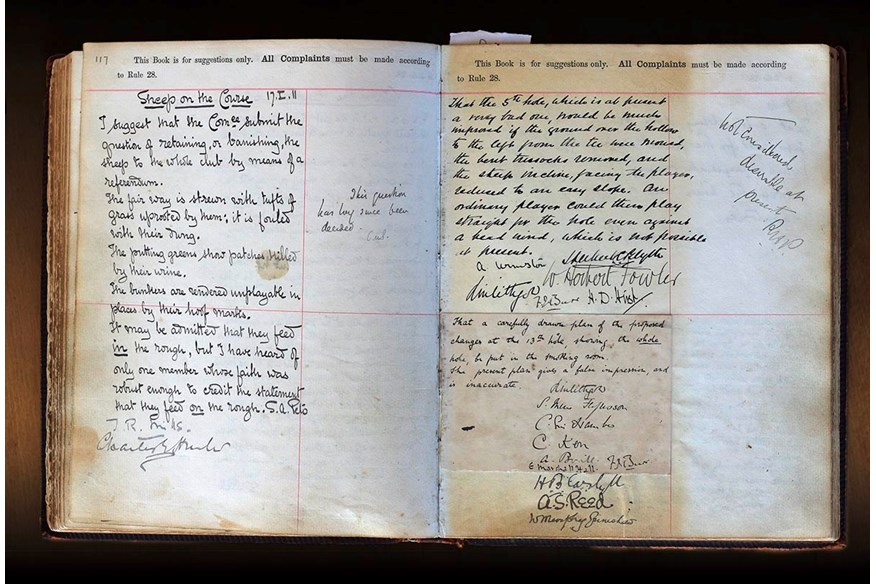

In 1968 there was an entry in the suggestion book that the club might consider buying a fruit machine. If you think that was a good idea then you just don’t get it. It would be like importing the flashing lights of Las Vegas into the Sistine Chapel.

“I’m in my eighth year and it’s been wonderful,” says club steward David Peregrine. “It’s like a really big family and the members make the club, they really do. I love everything about it. For a person my age, it’s just the best way to end my working life. I’m 65 now and they’ve extended my stay; so I hope to be here until I retire at 70.”

THE OPEN 2021: Win the ultimate Open Championship prize package

The large spacious bar, or Smoking Room as it’s labelled on the door, is classic St George’s, with its metal tankards for ale, leather seats and spacious feel. A first edition of Goldfinger, signed by Fleming, sits in the bookcase and a Lutine Bell is on the mantelpiece, a reminder of the visits of Lloyds of London, one of many societies with a deep history at Sandwich.

“If you’re on your own and you sit yourself down, it won’t be long before another member joins you,” explains the club president John Bragg. Then, as we admire a table that has a large metal, three dimensional map of the 6th hole, he recounts a story of a hole-in-one achieved by the late Brian Pope, who died last year aged 101. “He was in his 90s and needed a driver to cover the 150 yards. He asked me where it’d gone and I said ‘In the hole’, to which he replied, ‘About bloody time, my last one was in 1935’.”

Step out of a side door and you are in the sort of garden that would be the envy of a suburban household. A hedge acts as a border, but even the fields beyond are all owned by the club. “Cordon sanitaire,” mutters Bragg, “You keep a healthy space around yourself.”

The garden is uniquely St George’s. It’s tended to seven days a week and is useful ammunition in the rivalry that exists between the top clubs of the land.

When it was mentioned to one Muirfield visitor that a weakness of the home of the Honourable Company was their lack of a garden, he was heard to retort, “Garden? We’re a bloody golf club.”

THE OPEN 2021: Where The Open courses rank among Britain and Ireland’s links

The importance of lunch

A sign is positioned by the door of the dining room reminding those who are on their way out that they need to settle up. “Members are requested to discharge their bills at the desk before leaving the room,” it says. But it’s the date at the bottom that catches your attention, ‘March 26, 1890’.

“We haven’t changed the policy for 122 years,” says Bragg in a matter of fact tone.

The St George’s dining experience has been enjoyed by thousands for over a hundred years. At official functions, place names are used to encourage a mix of old and young, and there is a tradition of linen napkins. It is no coincidence that it is here that a giant portrait of Laidlaw Purves hangs, looking down with great satisfaction on the sound of chattering voices and clinking cutlery. The engine room of the club.

“Oh, the importance of lunch,” declares the secretary Colonel Tim Checkett. “People come down for the weekend and work in their golf around two good lunches. And it’s always traditional fare. There can be five or six huge roast joints on at any one time.”

Suggest a Mexican themed evening and you fall into the fruit machine category, and the hooks holding Dr Purves to the wall might just shudder and give way. George Chadwick is the chef and responsible for the menu. “I pinch myself sometimes that I work here. St George’s is special. It’s the members, the staff and the conditions we work in, plus we get to play a bit.”

The caddies

Jai Spicer is a wind and yardage consultant of the highest order. Forget your GPS or your adjustable driver, he’s a caddie who promises to save you shots. “That’s what the Americans call us,” he says, “wind, yardage consultants. I like that.”

St George’s has 130 caddies on its books, but today there are no more than a handful milling about. A conversation breaks out about the course, they are discussing every hole, shot by shot. “You must know about the 3rd?” says Spicer. “It’s the only Open Championship hole without any bunkers.”

THE OPEN 2021: Which golf courses host The Open and why?

Lots of nodding ensues amongst the other caddies. But, hang on, one of their number is staring at the ground with a furrowed brow. “What about the 18th at St Andrews?” says Andy Smallman. It’s decided that Sahara, somewhat ironically, is the only par-3 hole that doesn’t have a bunker. Spicer’s enthusiasm is such that it takes longer to talk about the first six holes than it would have taken to play them.

The Caddiemaster is Grant Leggate. He’s an ex-tank commander and he treats his men with the warmth of battles shared. They are his team. “I’ve been here two years now and it’s a dream,” he smiles. “I have a Wednesday off and my wife says I’m miserable on Wednesdays.”

He’s well aware that the caddies play a wider role than helping golfers to get the best out of their game. Spotting balls and maintaining a good pace of play are fundamental, not to mention ensuring that no visitors get lost. Two years ago some Koreans booked lunch, but when they reached the 13th green they wandered across onto Prince’s next door. “We got a call asking if we’d lost any Koreans. We told them ‘Yes, and their dinner’s ready’.”

St George’s doesn’t have a set rule on the cost of hiring a caddie. It’s a private agreement entered into by caddie and golfer. One of Leggate’s skills is to match personality with player. But if chatty is what you’re looking for then Jai Spicer might be your man.

On June 26, 1904, an entry was recorded in the club suggestion book that ‘Lady visitors should have the same privileges of the green and be subject to the same conditions, restrictions and payments as gentlemen visitors’. The committee wrote two words in the margin, ‘Certainly not!’ and the exclamation mark was not added by us.

Royal St George’s has always been a club where only men can be members. But before you write to Brussels or change your name to Pankhurst, consider a couple of things. Women can play there, do play there and have always played there. Furthermore, wives, girlfriends and daughters of members can play there for free.

THE OPEN 2021: Revealed – Who will win at Royal St George’s

Countless have chuckled at the suggestion that there was once a sign that read ‘No Dogs’ and in slightly smaller print underneath, ‘No Women’; but this seems to be nothing but urban myth. A similar sign did once exist outside the R&A clubhouse at St Andrews, but you won’t find it there now.

Royal St George’s is, you’d have to say, one of the few lasting bastions of male exclusivity, but it wouldn’t do to suggest that any such rule was demeaning to women.

There are no ladies’ tees per se because it is a men’s club, but some of the earliest photos are of women playing. The Curtis Cup was held there along with countless other ladies tournaments.

St George’s most famous dune is named after a woman and the last great spectacle at the club was instigated by a woman – one Holly Bennett – earlier this year. The Richborough Cooling Towers, three giant stacks, plus a thin chimney that, over 50 years, had become a defining landmark of the Sandwich skyline, and a perfect line to strike between Corsets on the 9th tee, were demolished.

It was Bennett who placed the fuses, while on the top of the Maiden a gathering of 50 St George’s members raised a glass of champagne. “We saw them collapse in on themselves and then there was a deep rumble that echoed like thunder,” says Checkett. Spontaneous applause broke out, not just on the dune, but amid a snaking crowd of a thousand or so along the bay road.

And as the dust settled, another chapter in Royal St George’s illustrious history was complete.

MORE OPEN PREVIEWS

What does The Open champion win?