Imagine not winning the Masters just because you made a mistake on your scorecard…

Published:

In 1968, Augusta National Golf Club witnessed one of the saddest episodes in the Masters history when, but for a wrong number signed on a scorecard, Roberto de Vicenzo might have won. But to remember him solely for this is to do the Argentinian a great disservice…

One of the Masters’ stranger quirks is that the tournament leaders get to watch the drama unfold, right along with you and me. A fateful fusion of muscular topography, long waits on reachable par 5s, switchback routing, and pine-amplified roars ensures that on golf’s most dramatic back nine, the players become acutely aware of what’s going on around them.

Creating its own pressure and intensity, it’s a phenomenon that can make even champions self-destruct; consider Seve Ballesteros, in charge of the 1986 Masters, undone purely by his unobstructed view of Jack Nicklaus’ eagle-birdie-birdie salvo from 15-17.

THE MASTERS: We’ve ranked EVERY player in the field at Augusta

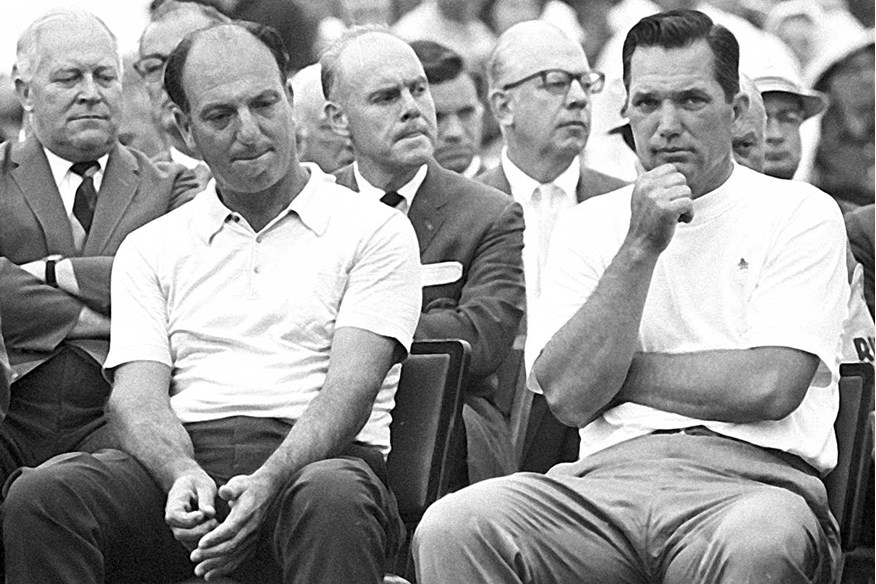

But 50 years ago, on April 14, 1968, it was two veterans – 39-year-old American Bob Goalby and Argentinian Roberto de Vicenzo, celebrating his 45th birthday – who were cast in this harrowing role of spectator-competitor. On Sunday afternoon, the two rivals were barely 30 yards apart – de Vicenzo on the par-4 17th fairway and Goalby on the par-5 15th. After holing his approach to the 1st, de Vicenzo had been holding off Goalby all day and by 17 still clung to a one-shot lead.

Pitching magnificently to 4ft, he looked across to see the shaft of Goalby’s 3-iron flashing in the evening sun. Even from the 17th fairway, the roars were thunderous; Goalby had rifled his second to within 8ft for eagle. If both players holed, they would be tied.

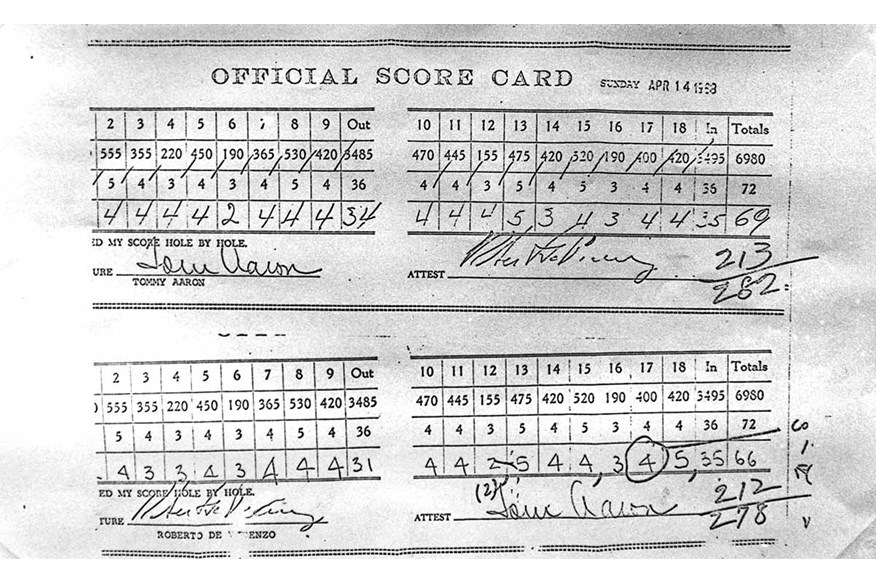

Showing great courage – short putting had been his nemesis – de Vicenzo secured his birdie to hold a fleeting two-shot lead. As he waited for partner, Tommy Aaron, to putt out, the explosion 500 yards down the hill told him he had been caught. Goalby had bagged his eagle.

On the 18th, for the first time that day, de Vicenzo blinked. A long, pulled approach led to his only bogey. He’d still shot a superb 65, but knew he had lost the lead. Devastated, he sat at the scorer’s table by the 18th green – an open and public spot just two club lengths from the gallery – and gazed blankly at his unsigned card. “I can’t forget what I do on first hole and last hole,” he said that evening.

“But to tell the truth, I don’t see any numbers.”

Aaron, also at the table, later recalled seeing de Vicenzo staring into space. Meanwhile, Goalby was nervously three-putting from range on 17. The two were tied again… but this time de Vicenzo hadn’t observed it. At this fateful moment, a press secretary beckoned de Vicenzo for an interview. He signed his card, left it on the table, and walked to the clubhouse. Glancing at it, Aaron’s blood went cold: he’d marked down a four for de Vicenzo at 17. The Argentinian had signed for a 66, not the 65 he actually shot. Even as he raised the error with Ike Grainger, co-chairman of the rules committee, Aaron knew the result.

THE MASTERS: The story of Augusta National’s iconic caddies

De Vicenzo had fallen foul of Rule 38-3, which stated ‘A score higher than actually played must stand as returned’. Informed of his mistake, he could only watch as Goalby, coming up the last, made a regulation par to tie his 72-hole score… and beat him by one.

In the half-hour of chaos that followed, Bobby Jones himself was consulted on the situation. But de Vicenzo knew that while Augusta National may be a law unto itself, that didn’t extend to rewriting the game’s rules. In the immediate aftermath – and indeed for decades to come – many asked why golf remains the only major sport where players are responsible for keeping their own score. But perhaps the finest answer to that lies in the instinctive acceptance of responsibility that illuminated this lifelong golfer’s memorable response.

After apologizing to Grainger for causing him so much trouble, and to Goalby for landing him with a victory potentially marked with an asterisk, he said: “I want to congratulate Bob. He plays so good, maybe he gave me so much pressure that I lose my brain. “This is my fault – nobody else’s. I have played golf for many, many years. I have signed many cards and none of them wrong. All I can say is what a stupid I am to be wrong in this wonderful tournament.”

Serial winner

It is one of golf’s ironies that one of its most successful players ever is best known for a failure. Put the 1968 Masters to one side and in de Vicenzo you have a golfer who claimed 231 professional victories worldwide, including the 1967 Open, six PGA Tour wins, and 48 national open championships in 17 different countries. De Vicenzo came second a further 127 times, and overall finished inside the top five on 490 occasions.

Though he spent most of his career avoiding ponds, de Vicenzo’s first experience of golf was diving into them – aged eight he became a ball-retriever at his local club, El Club Deportivo Mitre de Migueletes, in the Buenos Aires suburbs. Quickly he became a caddie, and began learning the game. “I taught myself with a branch of a tree and a cork ball,” he once recalled.

“It was just using my imagination. I’d compete with other caddies for the 10 cents it cost to go to the cinema. It was never easy because the cork ball would blow around in the wind.” De Vicenzo became infatuated with controlling the ball. Natural strength and talent meant rapid progress. At 15 he left school to become an assistant at Ranelagh GC, 12 miles south of Buenos Aires. Four years later he claimed his first victory, at the Litoral Open in Rosario.

THE MASTERS: Ben Crenshaw “There’s not much strategy left at Augusta”

Throughout the 1940s de Vicenzo established himself as Argentina’s nest golfer. He won 18 times in 26 starts in 1946, and with World War II over he began what proved an awkward international career.

Mark Lawrie, Royal & Ancient director of Latin America and the Caribbean, got to know de Vicenzo well during 15 years as chief executive of the Argentine Golf Association. “Roberto was never a full-time player on any tour,” he says. “Travelling from Argentina was prohibitive in terms of time and money; a journey to the Open meant three weeks on a ship with no practice… unless you count hitting apples off the deck. Roberto travelled until the money ran out… then he came home to teach and make more money to play.”

Nevertheless, de Vicenzo made his Open debut in 1948, impressively finishing 3rd, and played nine events on the PGA Tour that year. Travelling again in 1950, he claimed the Dutch, Belgian and French Opens and won twice the following year on the PGA Tour.

Then, discovering it cost $1,000 to fly to Miami from Buenos Aires but only $100 from Mexico, he decided to move. It should have kick-started his career, instead it rather stalled it. De Vicenzo would not win again in America until 1957, and in Europe until 1960.

He attributed his dip in form to his excessive teaching commitments, but perhaps a wider truth is that the role of a globe-trotting, cash-accumulating golfer never suited him. His talent and power made him a photo fit of today’s superstars. But his instinctively humble, non- acquisitive, home-loving character was anything but.

“I work for the money I need,” he said, “but the other money I no care much about. I’m more happy at home.” Nevertheless, de Vicenzo continued to collect minor American victories and gain admirers – not least Jack Nicklaus.

“At the 1957 US Open I watched him punch up a little tuft of grass with his brassie, then rip this shot that just seemed extra solid,” the Golden Bear recalled. “I always got that sensation watching Roberto.”

De Vicenzo’s lack of formal coaching showed in his fluent, natural action. His set-up was an object lesson in ready relaxation; hands placed gently on the club and plenty of room. A wide and full coil set up a smooth, rhythmical and powerful release, in the mold of a Sam Snead. In 1967, John Jacobs labelled him “as good a striker as anyone in the world today”.

THE MASTERS: Inside Augusta National’s clubhouse

Indian Summer

By 1967 de Vicenzo had won 160 events worldwide, but a major eluded him. His best chance appeared to be the Open, an event he cherished and that rewarded his innate creativity and imagination. Yet despite a superb record that saw eight top-10 finishes in 10 appearances, he seemed doomed to miss out. His best chance had been in 1960 where, having blitzed the eld with two 67s, he almost holed his second to the first… only to miss the putt.

“I miss that tiny putt, I can play no more,” he recalled. I no forget it all day. My blood, it boil over.”

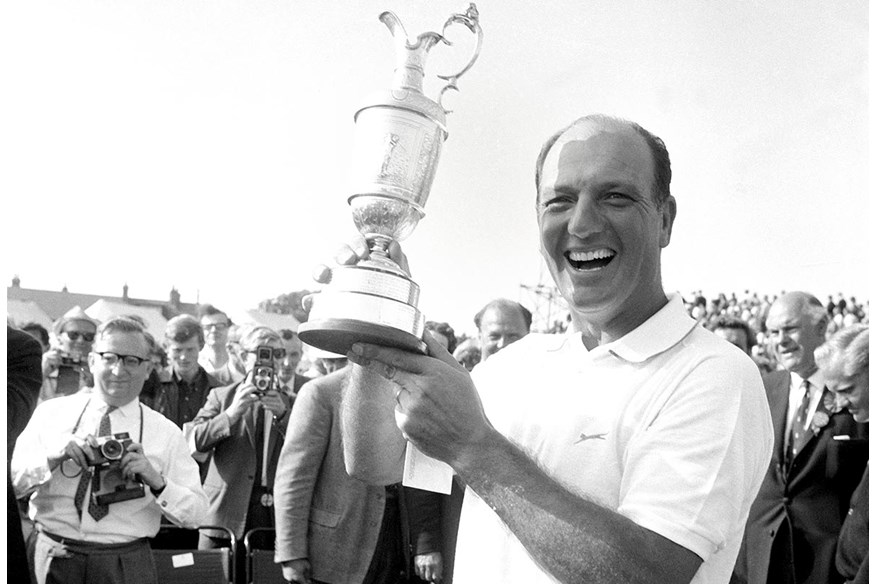

So when a 44-year-old de Vicenzo turned up at Hoylake – as ever in the old Bedford van he used when in the UK, painted pink and grey by his caddie, Willie Aitchison – the world saw him as an also-ran. Even the bookies gave him odds of 70-1. Publicly, de Vicenzo didn’t dispel the impression, suggesting he had returned to Hoylake “to play a little, but mostly to see friends.”

Privately though, he was buoyed by an exhibition match victory over Nicklaus and a recent win in the Roosevelt Memorial Nine Nations Trophy. He put £100 on himself. Playing beautifully, he began the final day two ahead of partner Gary Player and three ahead of Nicklaus. At the 16th, and still with a narrow lead, he pulled off the nest shot of his career, a 3-wood to 20ft.

“On the 18th tee Player turned and said congratulations, you’ve won,” de Vicenzo later recalled. “But there was still a hole to go. I played it with so much care and dread that my legs still shake when I think about it now.”

In the event de Vicenzo found the fairway and green, before two-putting safely for victory. His £2,100 prize was dwarfed by the £7,000 he collected from the bookies. The two biggest weeks of de Vicenzo’s career happened as it was starting to wind down. Had he signed for the right score nine months later and beaten Goalby in a play-off, he would have become the oldest player, barring Old Tom Morris, to win both events.

THE MASTERS: With anonymity guaranteed, the caddies reveal all about Augusta

While de Vicenzo would win tournaments right through to 1986, including the inaugural US Seniors Open in 1980, the ’67 Open marked his final victory in Europe, the following year’s Houston International his last on the PGA Tour. In 2000, playing the exhibition of champions at St Andrews, he announced to Nicklaus and Tom Watson

“This is my last drive in competition,” before smoking one 350 yards green-high up the 18th. “Part of me would’ve liked to have won more majors and been more famous,” De Vicenzo said in 2006.

“But my character is more comfortable where I have no obligation. I was not like Palmer, Nicklaus or Player. I wouldn’t like to be Tiger Woods. Their life has been one of work, of sacrifice. Yes, I played all over the world. But more in my own time.”

Don’t cry for me

Roberto de Vicenzo remained vibrant and competitive well into old age. He had always considered health his prime asset and rarely got a cold. He never felt so much as a twinge in his back, despite slugging the ball more than 260 yards well into his 80s.

In 2010, aged 87, he was dismayed that bad weather had cancelled St Andrews’ four-hole exhibition of champions. “I’ve got waterproofs,” he’d said. “Come on, let’s go and play.”

But early last year, the man who had become known as El Maestro suffered a fall and fractured his hip. He failed to recover and passed away on June 1, aged 94. At a memorial service, his life and contribution to golf was celebrated by an illustrious gathering, with Nicklaus leading the tributes.

THE MASTERS: What happened when our eight-handicapper played Augusta?

“Roberto de Vicenzo was not only a great golfer, but he was a great friend. He represented his country. He represented the game of golf. He was one of the really good guys.”

“In Argentina, Roberto is considered one of sport’s Big Five alongside Maradona, Fangio, Vilas and Monzon,” says Mark Lawrie. “Given golf remains a small sport in Argentina, that speaks volumes about the man.

“Quite apart from winning Argentina’s first major, he was rightly perceived as a fine gentleman.” Lawrie believes de Vicenzo’s legacy is two-fold. “He was one of the first to practise professionally. At his peak he’d hit 800 balls a day, then play afterwards. Today this is the norm, but then it was exceptional; other pros were at the bar, he was on the range.

“His second big legacy was to Argentinian golf. Vicente Fernandez, Eduardo Romero, Angel Cabrera, will all tell you when they went into the world of golf and told people they were from Argentina, they would be greeted with ‘Ah yes, Roberto! He played here. Come in, have lunch!’ Roberto opened doors for young players. Every Argentine pro is grateful for that.”

But despite de Vicenzo’s achievements, it appears his moment of tragedy behind Augusta’s 18th will be his legacy. However, in keeping with his glass-half-full attitude, even this would not have displeased him.

“All that I lose at the Masters is the jacket,” he once said. “The prestige? No. It’s many years in the past and yet we are still talking about the Masters. My name is in the Masters forever.”

MORE FROM THE MASTERS

– 2008 champion Trevor Immelman on beating Tiger and his injury heartbreak

– How you can play Augusta

– Everything the champion wins

– With anonymity guaranteed, the caddies reveal all about Augusta

-

A scorecard error cost Roberto de Vicenzo victory at the Masters.

A scorecard error cost Roberto de Vicenzo victory at the Masters.

-

A scorecard error cost Roberto De Vicenzo victory at The Masters.

A scorecard error cost Roberto De Vicenzo victory at The Masters.

-

Roberto de Vicenzo became Argentina's first Major winner at the 1967 Open.

Roberto de Vicenzo became Argentina's first Major winner at the 1967 Open.

-

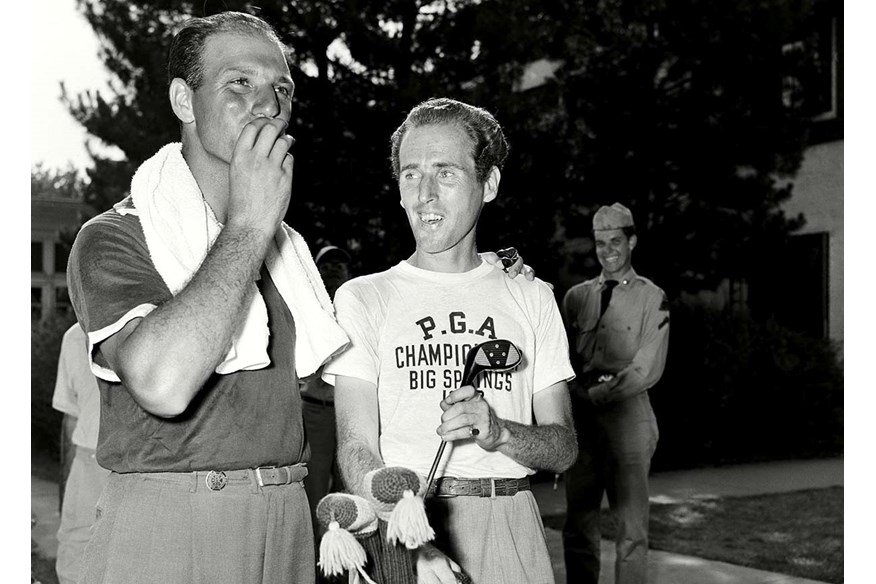

Another of Roberto de Vicenzo's 231 victories, this time on the PGA Tour in Louisville.

Another of Roberto de Vicenzo's 231 victories, this time on the PGA Tour in Louisville.

-

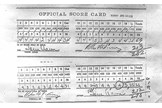

Roberto de Vicenzo's Masters scorecard, with the 17th hole error circled.

Roberto de Vicenzo's Masters scorecard, with the 17th hole error circled.

-

Roberto de Vicenzo reflects on the mistake that might have cost him the Masters.

Roberto de Vicenzo reflects on the mistake that might have cost him the Masters.