The tragic story of Augusta National course architect Dr Alister MacKenzie

Last updated:

Here, Peter Masters retells the glorious but ultimately tragic tale of Dr Alister MacKenzie.

When Bobby Jones bought a former Georgia fruit plantation with designs on creating a golf course, he called on the architectural services of a doctor of medicine from the Yorkshire Dales – and the rest is history.

Let us imagine, for a moment, flicking the clock back to July 1931 and a meeting between two ‘friends’ at an old nursery in the countryside, barely two miles from the Savannah River separating Georgia from South Carolina.

I say friends because these two are likely to have chatted a number of times over the previous few years, and this meeting, perhaps more business than pleasure, was one between two people who were now quite relaxed in each other’s company.

THE MASTERS: How Augusta will play for a November Masters

You can picture it clearly, the legendary amateur golfer Bobby Jones, all smiles and warm handshakes, welcoming Dr Alister MacKenzie to a place that was to become a lasting legacy to both men. Jones may well have known deep down what his Augusta National might become, but MacKenzie probably wasn’t aware of the significance as he turned into the drive.

For a start, it had been tricky to find, tucked away on Augusta’s north-west suburbs. Two small pillars with not much around them marked a drive so overgrown that it was like entering a car wash without any water. This was Fruitland Nurseries as it was, but it had lain dormant for the best part of 10 years.

The 365-acre plot had originally been laid out as an indigo plantation in 1854, but three years on Belgian nobleman Louis Matheiu Edouard Berckmans grew exotic fruit trees and flowering shrubs there for export around the country.

The first person to think of golf, as they stood gazing out from the white wooden veranda of the original plantation home, was Commodore J. Perry Stotz, who bought the land in 1925 with the idea of building a golf resort. But he went bankrupt before he could get started, and it was then, in 1931, that Bobby Jones, Clifford Roberts, and a group of investors purchased it for $70,000. So Augusta started blue, became multicoloured before settling on green.

THE MASTERS: What the tour caddies really think of Augusta National

It’s impossible to know what MacKenzie really thought as he first set eyes on this heavily rolling landscape. As canvases go, it could have been better. Building a good course on the side of a hill is never easy, and building a great one is asking for a touch of genius. But he also knew that Jones was a clever and creative man, and if he saw potential, then potential there must be.

It was 11 am when they met, there was probably iced tea in a jug, although you can’t be sure whether a Scotsman with English heritage or even an Englishman with Scottish heritage can ever buy into the cold tea idea. MacKenzie was born in 1870, the same year as James Braid and Harry Vardon, a year after Harry Colt, a year before JH Taylor, and two years before Donald Ross.

Alister was christened Alexander and was raised near Leeds in West Yorkshire to a mum with family roots in Glasgow and a father from the Scottish Highlands. So he was an English Scot.

Iced tea or not, Jones probably wasted little time before giving the good doctor a guided tour of the property. The eminent American writer Herbert Warren Wind tells us of the astonishment that greeted both men when they came to the foot of the long hill from the clubhouse and discovered the natural arcing amphitheatre that was to become the famous 13th hole.

Amen Corner (also a Warren Wind invention) might well have been created in reverse because Augusta was really all about the routing.

There are those who claim that Jones had quite a lot of input regarding the overall layout, but in David Owen’s book The Making of the Masters, he makes it clear that it was MacKenzie who came up with the routing, MacKenzie who positioned and created the greens and MacKenzie who then placed the bunkers. “Jones is sometimes given equal billing, or even first billing, but his role was more that of junior associate,” wrote Owen.

Augusta was also built at a time of debate about the best way to go, penal or strategic. Both MacKenzie and Jones were very clear on that. They didn’t like courses that were unnecessarily penal, preferring a design that was a fun challenge for all standards of player, hence the total absence of long grass and rough. There were fewer bunkers in the initial design as MacKenzie was moving away rather from the more flashy style that you can see at Cypress Point or Royal Melbourne, the two projects in the 1920s that really catapulted him into the architectural limelight. “He worked in a style that was appropriate to the era of depression when Augusta was built,” says Adam Lawrence, editor of Golf Course Architecture magazine. “It wasn’t about sand or water – what defined it were the contours of the land. You can take a flag stick and put it in a flat area and it’s a very easy hole; you can put it behind a little hump and it’s an almost impossible hole.”

The fact that, depending on pin placements, there are so many ‘no-go’ areas around the greens at Augusta is a testament to that. Indeed, every hole has a spot on the green where most of us would give ourselves a pat on the back for a three-putt. It is through the routing that is the most ingenious aspect of Augusta. Consider this: no two holes head in the same direction, and on the front nine, every hole has a different par from the one that preceded it. It’s only 10 and 11 along with 17 and 18 that are consecutive pars.

The shot values required for ultimate success are high. By that, we mean that great shots with perfect control are rewarded more than poorer shots are overtly punished. He who dares often wins at Augusta, but you do have to be good enough to take the risks to reap the rewards. Each of the par 5s, with the possible exception of the 8th, tempts the golfer to take on high-risk approaches when they know that a more conservative game plan can still pay dividends. It’s a course that asks questions at every turn, where no single strategy is necessarily the right one. A strategist’s dream.

The greatest of them all

A doctor of medicine who served in the Boer War, quite how MacKenzie got the Augusta commission is unclear. As is the question of how he first met Bobby Jones.

On the second of those points, the wise money seems to be on St Andrews – where else? Jones first played there in 1921, and didn’t much like it, but he returned for the Walker Cup in 1926, and there’s a suggestion that he probably chatted with MacKenzie about Augusta then.

Certainly, three weeks later, as he played in the Open at Lytham, the doctor was in the gallery, walking with OB Keeler, a golf writer and close friend of Jones.

Indeed, 1926 was a big year for MacKenzie. He travelled to New York in January and was commissioned to build Cypress Point in February. He returned home in March but then sailed to Australia in September, where he drew out plans for Royal Melbourne’s West Course.

You can probably see how this is coming together. Melbourne and Cypress Point were to become iconic landmarks in elite golf course design, featuring, along with Augusta, in the top 10 of most of the world’s top course listings.

When Jones played Cypress Point, having suffered a shock defeat in the matchplay section of the US Amateur down the road at Pebble, he was immediately besotted by the design. Soon afterwards, he played at Pasatiempo, another MacKenzie creation getting rave reviews, and was hugely impressed again.

In 1927, Jones defended his Open title at St Andrews, under the watchful eye of his new ‘friend’, and MacKenzie then sent him a signed copy of his book Golf Architecture, published in 1920. The pair discovered that they shared the same design philosophies, so it’s pretty safe to assume that as far as Augusta was concerned, the groundwork had pretty much been done.

From Medicine to Moortown

Alister MacKenzie had been a man of medicine in his 20s, partly because he was following a family tradition, but the interruption of wars helped him realise that his future lay elsewhere.

His interest in course architecture had really been sparked by the formation of the Alwoodley club near Leeds in 1907. His plans for the layout were admired by consultant Harry Colt, and the pair worked on the project together with MacKenzie taking the lead role.

His first solo creation was Moortown, which opened in 1910, and between then and the start of the Great War, MacKenzie became prolific around this corner of Yorkshire. He designed and dabbled at Harrogate, Headingley, Halifax, Horsford, Scarborough South Cliff, Darlington, Wakefield, Roundhay Park, Saddleworth, Reddish Vale, Leeds, Garforth, Dore & Totley, and Oakdale, which was opened three days before the country went to war.

His reputation was then expanded to a wider audience thanks to County Life magazine, which, in 1914, carried a ‘design a hole’ competition which MacKenzie won. He drew up an imaginary 420-yard par 4 that could be played in five different ways depending on the skill of the golfer and the weather conditions of the day.

So what makes a MacKenzie course? Most will refer to large undulating greens, while some talk about ornate bunker shapes with tongues of turf breaking up the symmetry of the sand, but in truth, it’s quite hard to grasp one thread and say ‘that’s classic MacKenzie’. That’s because he tends to work with what’s put before him – the land dictating the style.

He was one of the first designers to refrain from ‘ironing out’ large mounds on greens which is probably where the ‘MacKenzie greens’ reference comes from. He was on a train once and overheard a golfer from Hoylake tell his friends, “I think we’ve got some of those infernal MacKenzie greens.”

He quizzed him about it before adding: “Well, I’m Dr MacKenzie and I’ve never seen or even heard of your blasted course, so how I can be responsible for your greens I don’t know.”

Eddie Birchenough, the former club pro at Royal Lytham and a member at Cavendish, which was designed by MacKenzie in 1926, said this in defence of MacKenzie greens. “His designs are based on his green complexes. Some are built with severe slopes and borrows, others are flat. They are usually defended by mounds or slopes or bunkers with just one narrow entrance from a particular part of the fairway. To make this feature from the tee, he built his fairways 40 or 50 yards wide, knowing full well that only 10 of those yards simplified the approach. For years, Augusta was criticised for the lack of roughness, but only by those who did not understand the subtlety of the design. Even today, the edges of the fairway are cut slightly less short, just long enough to take some spin off the ball.”

Every architect seems to have a list of rules or principles that govern their approach, and MacKenzie is no different, listing 13 guidelines in his book. We can dispatch a lot of them as being predictable – not too hilly, minimum of blind shots, as good in the winter as summer, every hole its own character, making everything look nature-made.

More interesting perhaps was his assertion that the next tee should be a slight walk forward from the previous green so that there may be room for lengthening if required. Impressive forward thinking. He abhorred searching for a lost ball, so kept rough to a minimum, and would have been apoplectic if he’d seen Carnoustie in 1999.

MacKenzie liked the ‘two loops of nine’ routing scenario, felt that the majority of holes should be two-shooters, and that there should always be at least four par-3 holes.

Then there was this: “The course should so be arranged that the high handicap player should be able to enjoy his round in spite of the fact that he is piling up a big score. In other words, the beginner should not be continually harassed by losing strokes from playing out of sand bunkers. The layout should be so arranged that he loses strokes because he is making wide detours to avoid hazards.”

In this way, the less skilled golfer is playing to his handicap rather than being humiliated. MacKenzie expected you to tackle a course with a game plan and felt that many amateurs viewed the challenge before them in the wrong way. “Most golfers,” he said, “have an entirely erroneous view of the real object of hazards. The majority simply look upon hazards as a means of punishing a bad shot, when their real object is to make the game more interesting.”

Mackenzie created a home for himself just off the 6th green at Pasatiempo in 1931. It was said that he wanted somewhere he could go out and play in his pyjamas. But he barely had the chance to try golf’s equivalent of skinny dipping. For a man who rose over the course of a decade from little known to world-renowned, the end might be considered as shocking as it was quick and unexpected.

The end

The doctor died following a heart attack during Hogmanay celebrations to see in 1934. He lasted until January 6, when it’s said that his second wife, Hilda, brought him his lunch and sat chatting. As she was tidying his room, he suddenly gasped and died.

MacKenzie’s demise was met with shock and dismay, but it did provide Augusta with a solution to a problem that was proving hard for them to solve. They hadn’t paid MacKenzie his $10,000 fee for the work that he’d done. The club had been opened shortly after the Great Depression had set in during 1929, and there were moments in the early ’30s when it faced financial ruin.

Augusta took just 76 days to shape and contour, and the formal opening took place in January 1933. Jones had planned that the inaugural Masters would take place the following year.

The thought that the Masters would be preparing for the 83rd holding of the year’s first Major would, at the beginning, have been laughed at. Augusta barely had the resources to cover the $200 weekly wage bill of its staff, let alone the more handsome sum invoiced by its designer.

When his letters got no response, MacKenzie sliced his bill in half and then wrote these distraught words to the Georgia club.

“I am at the end of my tether, no one has paid me a cent since last June, and we have mortgaged everything. Can you possibly let me have five hundred dollars to keep us out of the poor house?”

It is thought that MacKenzie did eventually recover around $2,000 before he died, but that doesn’t seem much when you consider the recognition that Augusta National receives today.

It is arguably the most revered place where golf is played across the world, with the possible exception of St Andrews, and who designed that? Nature with a few digs from Old Tom Morris’ spade.

So it’s MacKenzie versus Nature, although many would say that nature was the greatest weapon in the medical man from the Yorkshire Dales’ armoury. He might have died unexpectedly and destitute, but his footprints in the world of golf have left the kind of indelible mark that will ensure that he’ll never be forgotten.

MORE FROM THE MASTERS

– The story of the Green Jacket… and how it was nearly peach!

– Augusta Icons: The story of Amen Corner

– With anonymity guaranteed, the caddies reveal all about Augusta

-

The tragic story of Augusta National Golf Course designer Alister MacKenzie

The tragic story of Augusta National Golf Course designer Alister MacKenzie

-

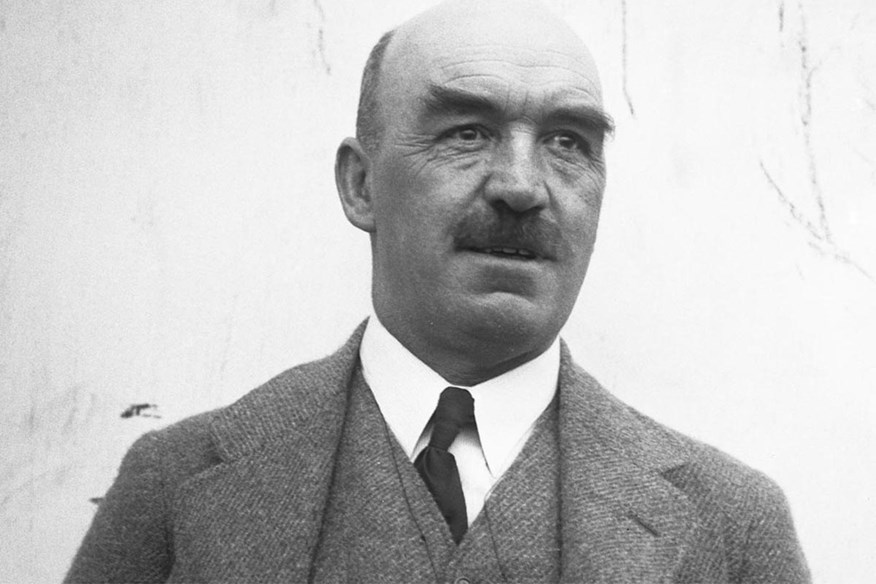

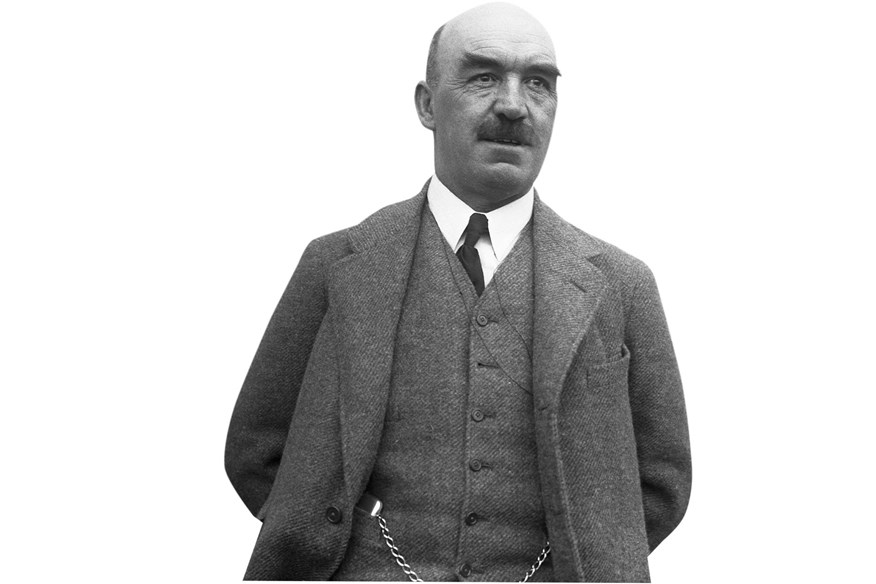

Alister MacKenzie was the architect of Augusta National.

Alister MacKenzie was the architect of Augusta National.

-

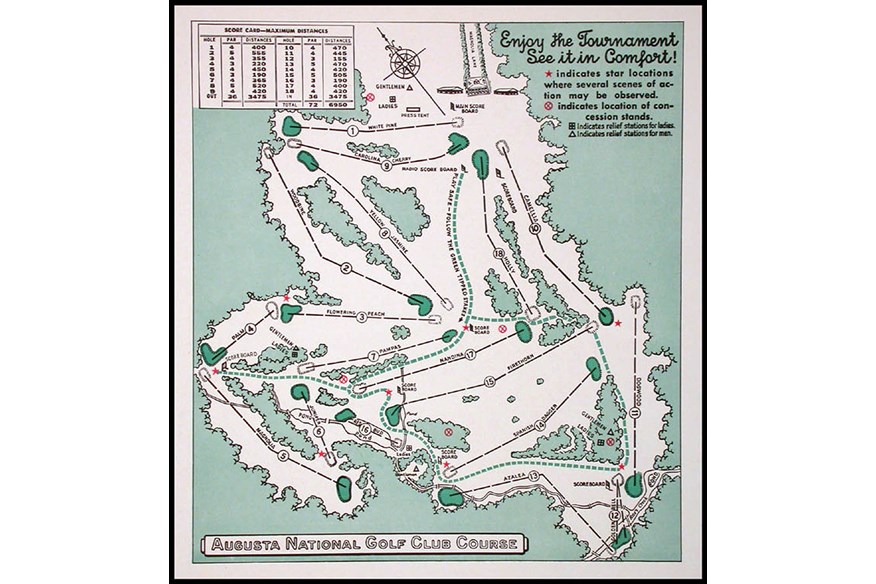

Augusta National golf course map

Augusta National golf course map

-

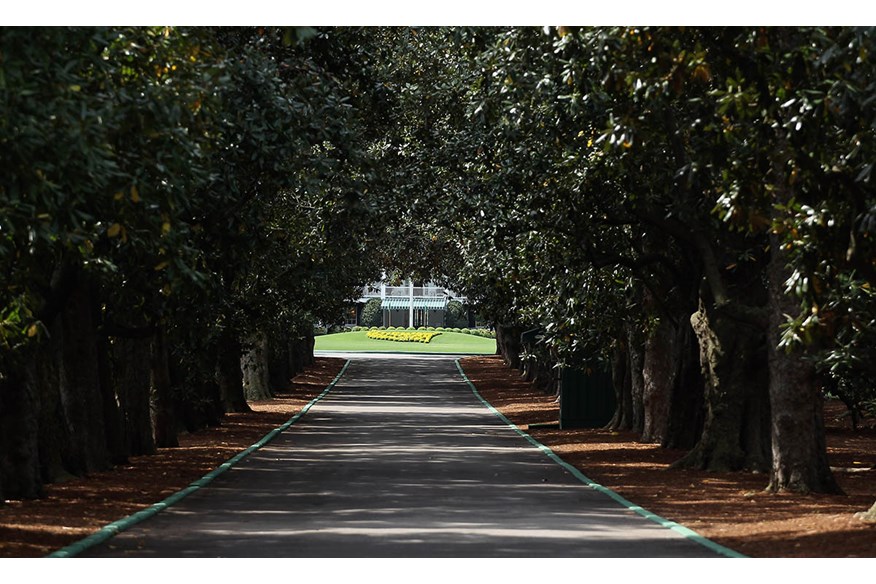

Augusta National's driveway didn't always look like this

Augusta National's driveway didn't always look like this

-

Augusta is probably the world's most recognisable golf course

Augusta is probably the world's most recognisable golf course

-

Augusta still undoes the world's best golfers to this day

Augusta still undoes the world's best golfers to this day

-

Augusta National has changed since the 1930s

Augusta National has changed since the 1930s

-

Alister MacKenzie designed dozens of top golf courses

Alister MacKenzie designed dozens of top golf courses