Pete Dye, TPC Sawgrass, and the incredible story behind the iconic par-3 17th

Published:

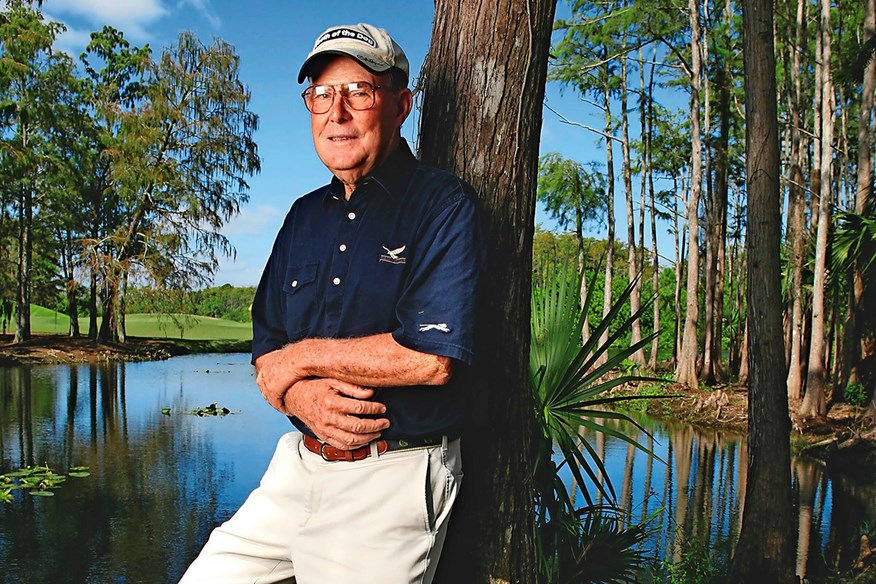

In his own words, celebrated course designer Pete Dye tells us what really influenced the famous island green at the home of The Players Championship.

Pete Dye was one of the most influential course designers of his generation. He brought us celebrated venues like TPC Sawgrass, Whistling Straits and the Ocean Course at Kiawah Island, host of this year’s PGA Championship.

Together with his wife, Alice, the Dye portfolio spanned over six decades and included more than 200 courses at the time of his death in January 2020. He was 94. The Dye legacy lives on today and can be seen in the eight original designs that feature in our Top 100 Golf Courses in the United States.

We had the pleasure of interviewing him in 2015, which gives an insight into his inspiration, his background, and why he was so in favour of rolling the ball back.

My father was in real estate and he became an avid golfer. My mother’s family had a lot of old farmland around Urbana and went out and built nine holes along with a group of people. It’s still there… and my youngest son, PB, added another nine holes 70 years later.

I qualified for the US Open in 1957 at Inverness, in Ohio. I remember checking in and looking for my locker. I found it, and saw that the next locker had been allocated to Ben Hogan. I thought “my gosh, what a thrill”. Then it turned out he couldn’t raise his arms above his chest and wasn’t able to play, so that was one experience I missed out on. It was a real shame. I missed the cut after a second-round 77 but I was in good company; I shot the same score as Arnold Palmer and was eight shots better than Jack Nicklaus.

I qualified for your Amateur Championship in 1963 and ’73 too, both at St Andrews. I used to go over early and play golf courses that people in America will never have heard of. I remember going all the way up north to Aberdeen and playing Cruden Bay, Murcar and Royal Aberdeen.

I joined the US military in 1944 and ended up in the parachute infantry in a rookie outfit called the 13th Airborne. I didn’t really do anything except jump, so when the war was over in August I still had six months to serve. I was back at Fort Bragg when the captain asked if anyone knew anything about golf – so I put my hand up. I ended up being the greenkeeper at the course! The captain used to pick me up every day and we’d go and play at Pinehurst. So I got to know Donald Ross, who also built the course at Fort Bragg.

Pinehurst stayed open during WWII and they planted Bermuda grass on the greens instead of oiled sand. But of course, everyone was used to playing sand greens in that part of the world so they kept top dressing it to keep them smooth. As a result, they raised those greens about 12 to 16 inches. Mr Ross kept telling me he was going to cut those crowns off! He died in 1948 so those crowns were never taken off. The owner told me he was going to take those crowns off, then he sold it, so those crowns have never been taken off… and those ‘dome’ greens have been copied all over the place since then.

When my wife Alice and I moved down to Indianapolis in 1950, I was made greenkeeper at the country club there. I worked as an insurance salesman, but was also doing agronomy courses – which I never passed – whenever I could. Then a farmer asked me to build him a course. I had tennis elbow that summer and couldn’t play golf so thought I’d do it. We thought we’d built Oakmont! Dr Harland Hatcher of the University of Michigan – which has 30,000 students – was driving past one day and he played it. He must’ve had the greatest round of his life because he called me and, even though I told him I didn’t know how to draw plans or anything technical like that, he hired me to build the university course. I’ve been digging dirt ever since.

Sawgrass was a swamp when I got there. But when you play the golf course and look at the tree line, you can see that none of the fairways have been raised. Somehow by luck I managed to do that, I think by using pumps and drains. You know, the lake on 18 where all that water is pumped to is six feet below sea level. So I had to do a lot of digging and when I got to 17 I found sand. I dug it all out to put it on the fairways and then had a huge hole left and no place to put a par 3. I said to Alice: “What am I going to do now?” She said: “Why not make it an island green?”

The club pro at TPC, Pete Davidson, took 100 balls out to the 17th at Sawgrass and hit 100 on the green. I don’t know why when they put that tournament there with all that money to play for, those guys make the worst swings all year. It’s only 130 yards and it’s not a small green. It’s 5,000 sq ft – it’s not a polka dot like the Postage Stamp at Royal Troon.

Tour players are hitting the ball so much further now. But then they always have. I’ve got a letter here in the house from Donald Ross. He writes that the ball was going too far… in 1923. But it is going so much further these days, and it does two things: it separates the Tour pro from the lady club golfer by 200 yards; and it escalates the cost of building (and maintaining) a course, because the owner might want to have a tournament there one day.

Some day, the R&A and the USGA have got to get a hold of that golf ball and make it so the pros can only hit it 260 yards, rather than 320. I can remember when I was playing half-decent golf; if you hit it 250 yards you knew you’d knocked it out of sight. Jack hit it 265. That’s a big difference to 320.

Golf can be about more than just the game. I went down to the Dominican Republic, where they wanted me to build a course in the capital – but I didn’t like the land. They told me they owned land out in the east. I asked how much. “550,000 acres,” they said. I said “there must be a course out there somewhere.” So I found a spot, but there wasn’t a road within 35 miles. Well, I built the Teeth of the Dog and now they have 90 holes down there. Best of all, 50,000 people work there. It’s not often you can create jobs for 50,000 people.