Paralysed PC Kris Aves: ‘I never thought I’d be able to play golf again’

Last updated:

It’s been just over two years since Kris Aves was left fighting for his life after getting caught up in a London terror attack. Doctors told him he’d never be able to move his legs again, let alone play golf. But with the help of The Golf Trust, The Shire, Mizuno and a Paragolfer, Kris is back doing the things he loves… and hitting drives further than you…

March 22, 2017. It was supposed to be a day of celebration for Kris Aves. Nine years a police officer, he was returning home to his family in East Barnet after a commendation ceremony at the Metropolitan Police Office HQ in London. Only he never made it back. At least not for another 10 months.

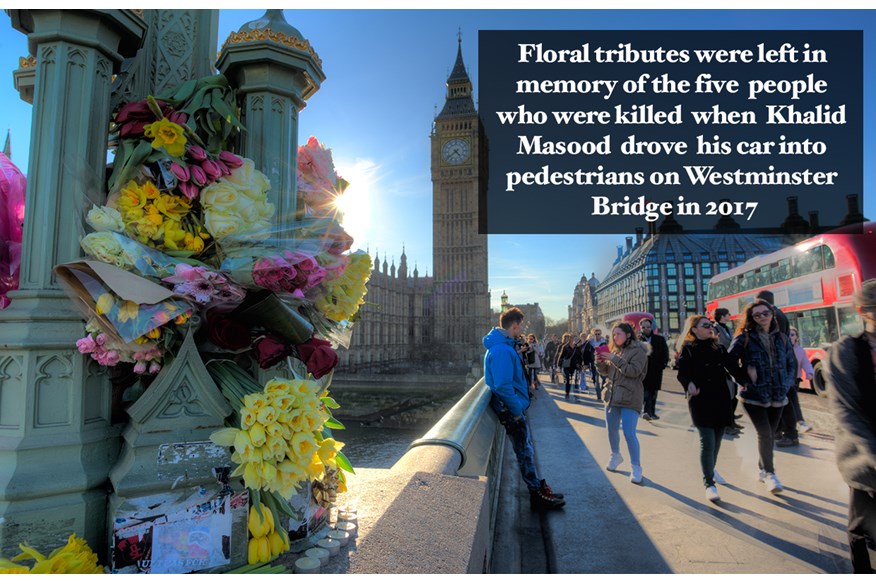

He can’t even remember collecting his award, or the events leading up to the terror attack on Westminster Bridge that left five dead and Kris fighting for his life after being run over by a 4×4.

“It started off as being one of the best days of my life to one of the worst – or the worst,” says Kris. “I was at New Scotland Yard in my tunic order, receiving a commendation and taking pictures outside of the River Thames, Big Ben etc.

“When we left, I can remember saying to a colleague, ‘I’ve left my umbrella upstairs’. He said, ‘It’s alright, we’ll get one of the other PCs to collect it for you’. That’s my last memory. My next blurry memory is waking up in Kings College hospital eight days later with a tube in my throat and my family around me.”

Unable to speak, Kris was forced to communicate through his mum, Julia, whose hand he would squeeze while she recited letters of the alphabet.

“The first word I was trying to spell was doctor, so I could get this tube out of my throat,” the 37-year-old explains. Over the next 72 hours, his partner, Marissa, and dad, Kevin, tried to fill in the blanks while doctors talked him through his life-changing injuries.

“From the chest or armpits down, there was nothing,” says Kris. “No feeling at all. My main injury which caused the loss of the feeling in my legs was between my thoracic three and thoracic seven. I’ve now got metal clippings in there because I dislocated my T4 and T5. By dislocating them, that squeezed my spinal cord.

“The main surgery was to release the pressure. Twenty four hours later, I went back in to repair fractures to both my tibia and fibula on both legs, and a compound fracture on my right leg.”

In the same way a policeman might reel off a list of suspects, Kris proceeds to document every injury he suffered, which included a fractured shoulder and sternum, a lacerated elbow and a torn right ear which, he hastens to add, was simply “sewn back on, good as new”.

“I also have three scars on my head,” he says, pointing to the affected areas in the clubhouse of The Shire. “But all the while, I was sitting in hospital, thinking about the three things I wanted to get back in my life. The first? My family, so my wife and two kids. The second, of course, was my love for Tottenham Hotspur and going to watch football. And then the third was being able to play golf. That was the one I knew was probably taken away from me for good.”

Kris’ fears were confirmed when doctors revealed he would never have any movement or feeling in his legs again.

“After hearing that…” he says, shaking his head, “I really thought, what’s the point? Before the accident, I had been playing golf once, maybe twice, a month for the best part of 10 years, and I loved it. I never joined a golf club or got an official handicap, but I started a society for the Camden Borough of Met police officers and actually had a golf day booked here [at The Shire] two or three days after the accident. Knowing I had to give stuff like that up was hard to accept. But, you know, life goes on.”

Over the next 10 months, Kris spent his weekdays rehabilitating at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Buckinghamshire, and his weekends living in a Travelodge.

“That’s because I couldn’t get into my house,” he adds, throwing his arm up incredulously. “My wheelchair wouldn’t fit.” The hardest part, he says, was being away from his family and only seeing his son, aged seven, and daughter, aged six, at weekends and during school holidays.

“A lot of the time I was saying goodnight to them over FaceTime, which isn’t right,” he says. “I wanted to give them a kiss goodnight.” Despite the tears and sacrifices, Kris kept fighting and would spend up to six hours a day doing hydrotherapy, physiotherapy and occupational therapy, hoping and praying he could prove the doctors wrong.

“It was tough, really tough,” he admits. “But slowly, I started seeing progression. I remember getting a little twitch in my left big toe for the first time since the accident. The day that happened, I also got a little bit of movement in my left ankle and started crying with joy. I was howling and the nurses came running over, thinking something was wrong. From that day, little movements started coming back and I got to the point where I could stand up, using a standing frame, and put some weight through my legs.”

Encouraged by his recovery, a group of physios arranged a trip to a local driving range, providing Kris with the opportunity to swing a golf club for the first time since the attack.

“I turned my standing frame around so my back was resting against it and made some one-handed hits,” recalls Kris. “That was my first time doing it like that but… it wasn’t right. I enjoyed it a little bit, but when there’s 15 guys on the other bays, smacking pitching wedges further than I was hitting a driver, it’s a little bit soul-destroying.”

Kris didn’t pick up a golf club for another six months after that and were it not for the intervention of The Golf Trust – a charity which works with disabled golfers in removing barriers to participation – he might have given up altogether.

“I was extremely lucky because a friend and colleague in the Met police put me in touch with Cae [Menai-Davis, one of the founders of The Golf Trust], who told me all about the charity and something called a Paragolfer,” says Kris.

“I didn’t know what it was so I Googled it, and saw this big wheelchair, kind of like a three-wheeler, which could move me from a seated position and into a standing position. A gentleman who lives up in Cambridge had one, so Cae got in touch and told him I wanted to try it.”

“That’s one of the best things about the disabled golf community,” explains Cae, who has spent the last nine months coaching Kris. “Everyone helps one another.”

“Do you remember when I got strapped in and I stood up in it for the first time?” Kris asks.

“Yes, because I only wanted you to hit about 20 balls,” replies Cae. “You ended up hitting about 100!”

Kris struggles to suppress his laugher, and admits his over-eagerness was born from the realisation that he would no longer need to use a wobbly frame to hit a driver 15 yards.

“The day I drove away from here with my partner, she asked whether it was my greatest day since I left hospital,” says Kris.”I was like, ‘Of course it is!’ Thinking back to when I was in hospital, I never thought I would be able to swing a golf club again.”

Keen to share Kris’ story, Cae uploaded a video of the first lesson on Twitter, which drew over 110,000 views and a message of support from Sir Nick Faldo.

“It just went crazy,” says Kris. “When Cae sent me a screenshot of Faldo’s message, asking Mizuno to get me some new clubs, I couldn’t believe it. I left that to The Golf Trust and Mizuno to sort, and sure enough they invited us down to Bearwood Lakes for a fitting. I was then given the full VIP treatment which was just amazing.”

Using the money raised from a charity golf day in his honour, Kris was also able to purchase his own Paragolfer, which he now stores behind reception at The Shire for the rest of the disabled community to use.

“He’s gone from hitting drives of 80 yards to over 200 yards in the space of a few months,” explains Cae. “He’s managed to play the academy course a couple of times, and four holes on the main course.”

“I even parred the 17th on the big boy’s course,” adds Kris, throwing his hands up in mini celebration. “The good thing is that little muscles are starting to flicker into life and because of that, my posture and power is coming back. I’m working with a private physio and am now at the stage where, using a walking frame, I can walk about 80 metres. My left leg is about 70 per cent active and then I have to use like a pace machine which sends an electric current through my muscles and tells my right leg, it’s time to move. Without that, I would probably struggle.”

The long-term goal is to be able to swap his wheelchair for a pair of walking sticks, but he accepts that the pain in his right leg may prevent that from ever happening.

“I do get severe nerve pain,” he admits. “At chest height, I get it really bad. And my legs also go into severe spasm. They either start jumping or try and stretch out, and I’m unable to bring them back in. I’m on numerous medications, but they do make me really drowsy. Normally between 4.30pm and 6.00pm I get really tired which is the most important time at home, getting kids ready for dinner and bath time. My partner probably thinks I’m having a tactical nap.”

He can make light of the travails of parenthood, since he’s now living back at his newly-renovated home, which featured as part of DIY SOS on the BBC last summer.

“They adapted everything,” says Kris, shaking his head in disbelief. “They made my bedroom and doors wider, they put a wet room in there, fitted remote-control curtains in my kids’ bedroom and built a stairlift. We got told afterwards that the BBC received their largest-ever number of applicants for one of their shows. To find that out was amazing. I still can’t quite put into words how thankful I am to the number of people who have helped me.”

In an attempt to give something back, Kris started fundraising for Stoke Mandeville hospital and raised over £7,500 after jumping out of a plane in September.

“I had to wear specially-prepared trousers, sent over from the States,” says Kris. “When I landed, they were all celebrating, saying ‘we’re so glad you landed OK’! I was like, ‘What do you mean?’ That’s when they told me it was the first time they had used the trousers. I was the guinea pig. Now, I think to myself, if I can do that, I can do anything.”

The next target, he says, is to get a golf handicap – a feat which has eluded him in his 11 years playing the game.

“Once I’ve done that, I want to play in some disabled golf opens,” says Kris. “Really, I just want to get on the course because I’ve missed not playing golf over the last two years. It might sound kind of corny, but it feels like I’ve got my life back.”

Fitting Kris for a set of Mizuno’s

Matt McIsaac, custom fit specialist at Mizuno, explains how they honed his clubs

“The beauty of Kris’ Paragolfer is that he’s able to get into a really nice, natural position at set-up. His posture mimicked your everyday golfer so apart from giving him slightly longer clubs, we didn’t have to change too much.

“As we do with all our customers, we used our DNA shaft optimiser which pinpoints the ideal weight and flex. The three recommendations we got were for two steel and one graphite. One thing I was wary of is that steel shafts can send too much vibration through the body, especially if you suffer from back pain or some kind of ailment. But the 95g steel shaft helped Kris to achieve a more centred strike than the graphite, and he didn’t suffer any discomfort which was key.

“Because Kris is still getting back into golf, and getting used to his range of motion, he was lacking in consistency, so it was a no brainer to fit him with the JPX919 Hot Metal irons since that’s our most forgiving and easiest head to hit.

“I think the only limitation now for Kris is how much golf he’s able to play. Distance isn’t an issue and if he can get into a nice groove, the only way is up because his golf swing is great.”

The Paragolfer: How Kris can Play again

• The Paragolfer allows for fast and easy adjustment of seat and lower-leg height, and raises the user from a seated to standing position in just 10 seconds.

• The stand-up functionality and unrestricted shoulder movement of the Paragolfer means Kris can play golf and do other activities including fishing, archery, and shooting.

• With a top speed of 10kmph, the wheelchair can overcome obstacles of up to 10cm in height and gradients of up to 17°. It retails at just under £20,000.

• The three-wheeled chassis and low pressure tyres on Kris’s Paragolfer are safe to use on all areas of the golf course, including greens and appropriately-designed bunkers.

What’s in his bag

Driver: Mizuno GT180 (11.5°); Tensei Orange 50 reg shaft.

3-wood: Mizuno ST180 (16°); Tensei Orange 50 reg shaft.

5-wood: Mizuno ST180 (20°); Tensei Orange 50 reg shaft.

Hybrid: Mizuno CLK (25°); Speeder 60 R2 flex shaft

Irons: Mizuno JPX919 Hot Metal (6-LW); XP 95 reg shaft