Maurice Flitcroft: The story of the ‘World’s Worst Golfer’

Last updated:

Maurice Flitcroft was not a golfer. But that didn’t stop him making multiple disatrous attempts to qualify for The Open. Now the ‘world’s worst golfer’ is the subject of a star-studded movie.

15 years after Maurice Flitcroft’s passing, a new British film will tell the extraordinary true story of how the chain-smoking crane driver from Barrow-on-Furness, attempted to qualify for The Open despite never having played a round of golf before. His efforts drew the ire of the golfing elite, saw him post the worst score in the tournament’s history, and ensured he became a British folk hero.

The Phantom of The Open, which has received rave reviews during previews, is an uplifting comedy drama directed by filmmaker and BAFTA Cymru Award winning actor Craig Roberts, from a screenplay by BAFTA winning writer Simon Farnaby. Farnaby, a golf lover whose father was a greenkeeper at Ganton. adapted the script from his own book “The Phantom of the Open“, which was co-written by Scott Murray.

The film stars Oscar winner Mark Rylance as Flitcroft, Golden Globe-winner Sally Hawkins as his wife, Jean, and Rhys Ifans as Keith MacKenzie, the R&A worker who became Flitcroft’s nemesis.

Here, in an extract from Farnaby and Murray’s book, is a taste of the story of Maurice Flitcroft.

Maurice Flitcroft had a dream. The chain-smoking crane driver wanted to win the Open Championship. And, despite the fact that he was a terrible golfer, he really believed that if he practised hard enough, and had a fair wind following him, the Claret Jug would one day sit on his rather dusty and shabby mantelpiece, alongside the empty tins of Golden Virginia.

Maurice had a number of different jobs during his lifetime. As well as driving a crane for eight years, he was a door-to-door salesman, an ice cream man and a stunt comedy high diver. ‘I did a season in Rhyl in Wales and my speciality was sawing myself off a diving board.’

RELATED: Mark Rylance on playing Maurice Flitcroft

But it was Flitcroft’s fixation with the Open which turned him into an icon, as well as one of the most eccentric golfers who has ever lived. He tried to enter the Championship on six occasions. Each time, officialdom eventually caught up with him, but not before he had exasperated a few, and entertained a few more. The Royal & Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews saw him as public enemy number one (they even employed a hand-writing expert to try to ensure Maurice didn’t slip through).

In later years he would reinvent himself, give himself false names and sometimes even a false moustache and a funny hat. He appeared on Breakfast TV with Nick Owen and Anne Diamond. Indeed, he was so famous, mail posted to “Maurice Flitcroft, Golfer, England” would regularly reach him at home in Barrow-in-Furness.

His disguises had to get ever more sophisticated, in order to escape the searchlights of the R&A. In 1978 and 1981 he entered as Gene Pacecki. (Ian Wooldridge, the famous sports columnist on the Daily Mail had written a piece about Maurice, stating that he was ‘a long way from making his first pay cheque; so Maurice’s irrepressible humour kicked in.)

In 1983, he posed as a Swiss professional called Gerald Hoppy (‘Gerald was my middle name, and my mother used to call me “Hoppy Johnny” when I was a youngster, because I was short as a kid, and couldn’t keep up with my parents and four brothers, so used to hop and skip a lot.’)

In 1990, he entered as a French pro who would only speak a little English, called James Beau Jolley; (‘my son is called James and I decided to call myself Beau Jolley because I had a dog named that, and my golf was as good as a fine wine’).

Maurice died in 2007 at the age of 67, having suffered from emphysema and an aneurism. This is an account of the first of six attempts he made to qualify for a Major, at Formby Golf Club, in 1976. The goal – to play in the Open at Royal Birkdale…

They eventually reached Formby Golf Club and set out to explore the course. ‘I set off to walk the course like a big-game hunter on safari,’ said Maurice, ‘with my cream shirt, fawn slacks and red jungle hat, notebook and pencil at the ready, to weigh the links up and plan my strategy for the first qualifying round the next day.’

He was accompanied by his niece Sandra, who had kindly offered to show Maurice the route to the course. She explained her directions calmly and patiently, in the sort of soothing tones these days generated by satellite navigation systems in high-end executive saloons. Her efforts were however wasted on Maurice, who was in a world of his own and heard not a single word, taking a couple of wrong turns, learning nothing.

It wasn’t long before the relentless sun took a sorry toll. Maurice began by making incredibly detailed notes of every bunker, bush, hump and hollow, making a particular effort to stride out 150 yards to each green from the fairway where he planned to employ his favoured 4-wood, creaming each and every one towards the flag. This felt good. He was acting like a pro now, formulating one hell of a watertight strategy. If he executed this to the letter, ran his train of thought, he had a real chance of making Birkdale the following week.

RELATED: Best Golf Courses in England

Alas, after two and a half holes, something snapped in Maurice’s head: ‘It wasn’t long before I began to get fed up with this lark and decided to just rely on my judgement.’ It didn’t help that it was approaching midday, the sun beating down from its most sapping position. He called off the scouting mission and retired to the clubhouse. This was of some relief to Sandra, who was beginning to feel faint with the toxic mixture of sunstroke and extreme boredom. It’s bad enough to walk the course watching someone play if you have no interest in golf; watching them pace out distances between clumps of heather and a pot bunker in a furnace was beyond the pale.

Back at the clubhouse, Maurice was about to be given a rude awakening. Incredibly, despite this being the eve of his Open debut, he had never actually stepped inside a golf clubhouse before, used as he was to hopping over fences and playing in the moonlight before scampering off into the darkness, usually with an irate member in hot pursuit. This would be his introduction to the etiquette of the golf club, a labyrinthine tradition of strange rules and illogical diktats. And it would be a baptism of fire.

Maurice was about to unwittingly lead his niece not into the family-friendly unisex lounge, but into that anachronism seemingly unique to golf clubs. They were entering the forbidden zone, the hallowed sanctum, the motherlode. They were making their way into – Wagnerian drum roll – the men-only bar. And he was still wearing his hat!

The thirsty pair innocently sauntered into the room and waited patiently to order some refreshing squash. En-route, Maurice had heard a succession of forced coughs by two ruddy-faced military types in ill-fitting blazers, one sporting waxed eyebrow turn-ups, the other a ludicrous wispy comb-over. Major Eyebrows and Captain Combover had specifically designed their hacks and splutters to galvanise the woman serving behind the bar into action, though she needed no direction. She had already spotted the two hapless rule-infringers.

‘Two pints of orange juice and soda please, love,’ Maurice ordered, oblivious to the pairs of staring eyes piercing his back.

‘Sorry, sir, but you’ll have to take your hat off before I can serve you,’ replied the bar lady, pointing at the floppy red jungle headgear Maurice had wedged on his head to stave off the intense heat.

‘Eh? Why?’

‘Because those are the rules,’ the lady elucidated calmly and clearly.

Maurice’s eyes narrowed. His natural inclination was to assess ‘whether the situation was getting heated, and whether it merited a sharp response’. His inner monologue concluded that while it might be, at this stage it probably did not. Yet. He swiped his hat off his head sharply and stuffed it in his pocket. Maurice was not constitutionally able fully to acquiesce to anything, so he appended the movement with a facial expression that unambiguously asked: ‘Satisfied now?’ He then repeated his order of two pints of orange and soda.

Another explosion of coughing erupted from Major Eyebrows and Captain Combover. Maurice wondered whether they’d caught Spanish Flu. The bar lady, finally responding to the coughs, nods and eyebrow-waggles of the retired servicemen towards the interloper from the distaff side, finally gave up wrestling her sisterly urges.

‘There is another matter, I’m afraid,’ she stammered, replicating the pointed glances towards Sandra. Maurice decided that the heat had caused some kind of collective madness to envelope the environs of the bar.

‘I’m not with you,’ he responded.

The bar lady was finally forced to state the club’s position. ‘I’m afraid the young lady will have to go outside,’ she whispered, her cheeks deepening to crimson.

‘Why?’ asked Maurice, immediately snapping into chivalry mode.

‘Because this is a men-only bar,’ came the only explanation.

‘A what?’

‘This is a men-only bar. Ladies must go outside, or use the lounge,’

Maurice was utterly perplexed. He knew, of course, of the working-men’s clubs across the north of England, but they were more often than not populated with women anyway. What was the point of this, he wondered? Yet again, Maurice displayed attitudes years ahead of his time. But he had yet to work out that, if the world was a couple of decades behind him, the golfing firmament was at least another half-century further back. He first confronted the obvious contradiction in the club’s policy.

‘What are you doing here, then?’

‘The rule doesn’t extend to employees, sir.’

‘I’ve never heard anything so ridiculous in my life. It’s a hundred degrees out there and cool in here! We’re thirsty. Please, now, we just want our drinks.’

Major Eyebrows had heard enough. He finally folded his Daily Telegraph, placed it purposefully on the table, hoisted himself out of his seat, and approached the offending duo. ‘Perhaps I can be of assistance,’ he pompously puffed. ‘She is quite correct, I’m afraid, this is, in fact, a men-only bar. Rules are rules, I’m afraid, old boy.’

Captain Combover, having advanced to the bar, placed his hand on Maurice’s shoulder and gestured to the door. The rebel from Barrow was being offered a face-saving out: meekly accept the status quo, smile politely at the misunderstanding, and quietly disappear with Sandra into an area where women were permitted to imbibe orange squash. But he was disinclined to make any sort of grab for the opportunity, preferring to embark on a Hegelian dialectic with his new military chums in search for a higher truth.

‘Listen, pal,’ Maurice spat, making sure to immediately extract any confusion from the situation, ‘this is my niece, and I am playing in the British Open here tomorrow, so if I were you I’d show a bit more respect.’ The Major was momentarily taken aback by these revelations, as he glanced up and down Maurice’s eccentric safari ensemble. ‘If Jack Nicklaus came in here with his niece,’ added the Open competitor, ‘I don’t suppose you’d be so quick to turf them out, would you?’

Aware that several of his cronies were now peering over their Telegraphs and listening intently to developments, Captain Combover stepped up a gear to save face. ‘It wouldn’t matter if old Tom Morris himself were to leap from the grave and stand before me with his wife and daughter, rules are rules and this is a men-only bar.’ It was a splendid bon mot. The quality of the quip only served to irritate Maurice even further.

‘Let’s just go, Uncle Maurice, I’d rather go outside anyway,’ pleaded Sandra, fully aware of her uncle’s appetite for confrontation. What she didn’t know was that the last time he defended a lady’s honour in front of an authority figure, said authority figure ended up sliding across the top deck of a bus on his chin.

‘We’ll leave if you’d be so kind to tell me exactly why women aren’t allowed in this bar,’ demanded Maurice.

‘Because it’s the rule of the club, one that’s been rubber-stamped by the committee,’ spluttered an exasperated Major Eyebrows, highly irked at being questioned.

‘Not good enough.’

Captain Combover tried the jauntiness angle – a staple argument of the casual bigot who has genuinely convinced himself that the men-only rule is doing the ladies a favour. ‘Well, I am all for women’s lib, old boy, but why would a woman want to be in here anyway? It’s awful, it’s full of men!’ The joke fell on deaf ears.

‘Not good enough.’

The major snapped, his manicured eyebrows vibrating like a hummingbird’s wings. ‘The reason women are not allowed in the gentlemen’s bar,’ he shuddered, ‘is because over here is the entrance to the male changing room.’ Unused to having to explain himself, he marched towards a door adjacent to the bar in order to deliver the killer blow. He flung it open. Through a chink of light at the end of a wood-panelled locker room, several overweight gentlemen could be spotted in various states of disrobe, some talc-ing up, some flossing their clefts with the sharp edge of a towel in the inimitable fashion, most staring blackly back into the bar, like wide-eyed deer staring down the barrel of a shotgun. Sandra let out a shrieking guffaw. Finally a voice from the changing room cawed for the door to be closed with immediate effect, if not sooner.

Maurice conceded defeat. Having swallowed his pride, he necked his orange juice with Sandra outside on the patio. The pair gathered themselves up and headed back to base camp at Skelmersdale.

The Wrecking Shot

After a light lunch, Maurice wandered off to some nearby fields to practise. On the way there he gave himself a pep talk. ‘I decided that there wasn’t much time left to make radical changes to my swing, so I would have to make do with what I had. I did feel, however, that a satisfactory practice session would do wonders for my confidence.’

He began by hitting some short irons. He was finding the sweet spot, so he graduated to his medium irons, then long irons. Satisfied that they too were in decent-enough shape, he took out his nemesis: the driver. ‘I knew that the ability to hit a good drive was going to be an important factor the next day,’ he recalled, ‘so it was with some misgivings that I found my driver was not what it should have been.’ The trouble was with a certain kind of shot that set off straight and powerful, yet veered horrifically to the left after sailing about 50 yards through the air. This shot is known to most golfers as the snap hook. But Maurice had never played with any other golfers, and had no shared parlance to identify it, so coined a phrase himself: ‘The Wrecking Shot’. The harder he tried to fix The Wrecking Shot, the worse it got. When the light faded, he still hadn’t found the solution. Consumed by concern, he trudged back for dinner. He had a long hot bath and thought about The Wrecking Shot. He went to bed, tossed and turned. Trying anything to take his mind off The Wrecking Shot, he eventually found the perfect solution. He pulled from his suitcase a book he’d been reading, Golf Rules Illustrated. Within seconds of opening the book Maurice fell asleep.

RELATED: Best Golf Practice Nets

He had set his alarm for 5am, but awoke an hour earlier, bright as a button. After a slurp of tea he was out in the fields again with his driver, in the hope that The Wrecking Shot had miraculously disappeared overnight. To his horror, he discovered it was still there; and resolved to use his favourite club, the 4-wood, off the tee instead.

He set off for Formby with two hours to spare, which should easily have afforded him half an hour’s practice on the range. Unfortunately, having failed to listen to Sandra en route to the club the previous day, he soon got lost, misreading a signpost with devastating consequences.

‘I found myself heading in completely the wrong direction,’ he said. ‘Not sure of the route I should be taking to rectify the error, this necessitated me driving slower than I normally would. All of which began to make me anxious. I couldn’t afford any more mistakes. I’d already used up the time I’d set aside for warming up and now I’d be hard pushed to make it to the course on time for teeing off.’

He eventually arrived at Formby with only a few minutes to spare, tearing across the gravel car park in a desperate attempt to find a parking space. First, he needed to buy some golf balls. The club pro, Jimmy Hulme, witnessed Maurice bundling into his shop, wearing a ‘shabby cap and a pair of gumboots’. Hulme told him to get out, that nobody needed a caddy. Maurice replied that he was here to play in the Open, and that he needed some balls.

‘How many will I need to get round?’ he asked. Barely stifling laughter, Hulme spotted an opportunity to make a few quid and sold him a dozen. Maurice then explained that he would require a caddy. With time tight, Hulme busied himself arranging one, telling the shabby pro that someone would arrive at the tee very shortly. There was no time to change in the locker room, so Maurice pulled his shoes on while standing by his car, a complete no-no at any self-respecting club and an act which received one or two pained looks from passing members. Were Major Eyebrows and Captain Combover to pass now, he would surely be chased down the road, Maurice surmised. He knew he had one too many clubs in his bag, so pulled his errant 2-wood out and hurled it in the boot. Then, red-faced, he scampered off to the first tee, just in time.

There he found his caddie waiting, a teenage lad who made up for his lack of years with callow enthusiasm. Anticipating a hot day, he’d already soaked some towels in iced water and handed one to Maurice. A ball had yet to be struck in anger, but on this blistering day the towel was much needed; Maurice was drenched with sweat after his hair-raising journey. He shook hands with the announcer, who checked his watch and picked up the microphone.

‘On the tee,’ the announcer trumpeted, ‘unattached, Maurice Flitcroft!’ A polite smattering of applause. Maurice turned to his caddy. ‘Four-wood please, son.’

The caddy looked confused.

‘Erm, there isn’t one. You’ve got a driver and a 2-wood.’

Maurice’s newly aligned world suddenly span off its axis again. The full horror of the situation snapped into harsh focus. In his haste to make the tee on time, Maurice had whipped his 4-wood out of the bag by mistake and left that in the boot instead of the 2-wood. He allowed his disappointment a verbal outlet: ‘S***.’

Jim Howard and Dave Roberts, Maurice’s two playing partners, shot concerned glances at each other. Then Maurice remembered where he was, and steeled himself. This was it. The British bloody Open. Time to stand up and be counted.

‘I felt everyone’s eyes on me as I stepped purposefully forward,’ recalled Maurice. ‘After lining up my target, I took up my stance, addressed the ball, checked my aim, then swung the club mightily and let fly.’ The ball sailed through the hazy summer sky.

His ball went in an almost vertical direction. Upon landing, it was clear that it had not been imparted with too much forward momentum. It had only just cleared the end of the tee, ending up 40 yards down the track. The decision to use a 2-wood instead of his potentially ‘round-wrecking’ driver had already backfired.

‘To my horror,’ said Flitcroft, ‘the tendency to hit a certain kind of shot with my driver also applied to my 2-wood. It was not a total disaster. It could have gone straight up, come down, and hit an official on the head. But it didn’t, I’m glad to say.’

The die was cast. Maurice’s next shot was shanked into a filthy patch of rough. Down the fairway, Dave Roberts and Jim Howard waited patiently. Very patiently. Maurice’s third shot came off the hosel and squirted off at an odd angle into a fairway bunker. The scruffy pro from Barrow negotiated the rest of the hole without further drama. With the burning gaze of Howard and Roberts already causing his skin cells more damage than the blistering sun, Maurice completed the hole with a triple-bogey seven. Three over par, after one hole.

Howard and Roberts, already discombobulated, had not been slow to take action. They could see – after the 1st hole, after the first couple of shots, even back on the tee – something wasn’t right. Roberts had his wife caddying for him, and she was swiftly dispatched to the clubhouse in order to inform an R&A official.

RELATED: Most Forgiving Drivers

Maurice took five at the 2nd, followed by a six at the 3rd. It was the most auspicious of beginnings to a round, never mind a professional career, but Flitcroft wasn’t the first pro golfer to begin a round 7-5-6 and he wouldn’t be the last. But while many a professional has indeed began a round 7-5-6, few follow it up with another three sixes. Fewer still follow that up with a scorecard-wrecking, legend-defining, infamy-sealing, double-figure hole.

‘The big one was the par-5 7th,’ explains Roberts. ‘It’s a long hole through sand dunes, nearly 500 yards. Because of the elements and the weather, the ball was running quite a way, and his bounded into the sand dunes.’

The ball was not quick in coming back out of them. Maurice, his exasperated playing partners up ahead, worked like a dervish to hack his ball out of trouble and back onto the fairway. It became an increasingly futile effort. By now, his idiosyncratic jazz stylings were causing hold-ups, with threeball after threeball backed up behind Flitcroft, Howard and Roberts. An Australian voice from a parallel hole was raised in protest, questioning the fisherman-hatted fiend’s ability. Maurice stood his ground as proudly as a man can while bumbling around a sand dune and repeatedly swinging a metal stick at a seemingly immovable object.

‘An Australian complained that we were holding them up, that he had gone to a lot of expense to get there, as though I hadn’t!’ said Maurice. ‘I don’t remember what else he said, but I do remember that I replied that it was an Open championship, and that I had paid my entrance fee and was perfectly entitled to be there.’ Unsettled, Flitcroft completed the hole in 12 strokes.

Even then, this was a kind reading of events. For a couple of holes later, a member of the threeball directly following the Flitcroft match, Harry Bannerman, sidled up to his friend Roberts and enquired as to what the hell was going on.

‘What did that guy take on the 7th?’ whispered Bannerman.

‘He took 12,’ answered Roberts with a thin smile that could easily have been mistaken for the tired grimace of a man weighing up the downside of a lengthy spell inside, with the cathartic joy of wrapping the business end of a 7-iron around a crane driver’s neck. ‘Twelve?’ spluttered Bannerman, with a mixture of incredulity and high amusement. ‘He took that many shots behind that sand dune!’

‘We didn’t know how many shots he played, we couldn’t see him,’ admits Howard now. ‘It was very farcical, you know.’ Roberts scribbled a question mark next to the 7th hole on Flitcroft’s card, and moved on with a heavy sigh.

Thirteen more shots over the next two holes took Maurice to the turn in 61 strokes, a massive 25 over par after nine holes that seemed like 99. ‘Formby is a course that goes all the way out, and goes all the way back, so you can’t come in at the 9th,’ sighs Roberts. ‘Because we’d have just walked in, you know.’

Just after the turn, Maurice suffered another double whammy. At the par-5 10th, he ran up a card-bothering 11, ensuring the inward half of his round would be equally as lame as the outward. It was at this point that an R&A official approached him for a quiet word, mano a mano. Exactly what was asked has gone unrecorded. All Maurice reported in his memoir was that the official wanted to ‘find out what he could about me, judging by the questions he asked’ and that the situation soon became ‘heated’.

Responding to one of the official’s whispered queries, Flitcroft replied with feeling and no little volume. ‘I was replying to one of his questions when, to my surprise, he suddenly said ‘Sh-h-h!’ which I didn’t think very polite, and to which I didn’t take kindly. I snapped back that he had asked me a question, and I was answering it.’

RELATED: Best Golf Courses in Britain and Ireland

The fact that Roberts was concurrently taking his shot just across the fairway, just within earshot, did not cross Maurice’s mind. ‘So far as I was concerned, if our conversation was distracting the player about to swing, that player would have been well advised to wait until we had finished,’ he reasoned. ‘The fact that he went ahead and played his shot would indicate we were not distracting him. On the other hand, the official could have chosen a more opportune moment to quiz me.’

After the R&A official scuttled off with his tail between his legs, tempers within the threeball became frayed. On the 12th, Maurice was surprised when a blind wedge shot from deep rough in a hollow generated cries of alarm from Howard and Roberts. ‘I could only assume it had just missed them,’ said Flitcroft. ‘My caddie confirmed this. It was a nice shot out of trouble, for all that.’

The stroke didn’t just send an increasingly pensive Jim Howard darting for cover, it also forced him to contemplate deeply existential issues. ‘What a way to make a living!’ he remarked during a lull in battle, staring straight at Maurice. An innocent aside, but one that raised the crane driver’s working-class hackles. His inner monologue ran thus: ‘I am surprised to hear a professional golfer make such a remark, not that I have known any before today. I will not reply. But if I was going to, I would say that it is preferable to working in a factory, a foundry or down a coal mine.’

Tension also crackled between Maurice and Howard as a result of the former marking the latter’s card. Already struggling to keep his own score, Maurice would invariably lose count of his opponent’s, too. ‘So, on a number of occasions,’ he explained, ‘when I wasn’t sure, rather than guess how many strokes the other player had taken, I would ask how many he had taken. It was something I was entitled to do, and he was obliged to tell me. He did so in a grudging manner, which I thought rather churlish.’

Maurice was non-plussed at the increasing opprobrium coming at him from all angles. ‘I noted their disapproval, but I did not let it bother me,’ he would write years later. ‘Why my apparent lack of ability should have bothered them, I’m at a loss to understand. One thing was for sure: I didn’t pose a threat to their chances of qualifying, which should have given them a psychological advantage.’

Nevertheless, Howard was losing all appetite for his Open challenge. A native of nearby Liverpool, he had invited several of his old friends along to their local course to watch him complete for a place in golf’s biggest championship. ‘Friends of mine had come to see me play, and I ended up with nobody watching me. However, a crowd of two or three hundred people had gathered to follow us as a curiosity.’

Word had got round the course of a singular event unfolding. The hubbub whetted Maurice’s appetite for nothing so vacuous as fame or notoriety, but old-fashioned glory, an attitude betrayed in his flight of fancy: ‘The club probably employed a runner, a fleet-footed young man or woman for such purposes, just as they did in the old days, to carry news of victories on the battlefield, or defeats, back to their waiting masters and the people at home!’

After a steady five at the 11th, a borderline-acceptable six at the 12th, and a not-crushingly-calamitous-given-what-had-gone-beforehand eight at the 13th, Maurice stood on the 14th tee gaining succor from the ever-growing gallery following his progress. He was about to play the greatest hole of his professional career to date.

What exactly happened on that par 4 – the second-longest on the course at 420 yards – will never be known. But there are two distinct reports. The first was penned by Bill Johnson, the press officer stationed at Formby by the R&A that day, with a remit to keep in contact with the central press office at Birkdale, where the Open proper would be held the following week. Johnson’s report details a drive into rough, a hack back onto the fairway, a thinned iron to three feet, and a tap-in for par.

The other report is by Maurice himself, who recollects ‘a super 3-iron off the tee’; an ‘online’ iron shot (albeit one that finished well short of the target’); a 9-iron which was ‘caught a bit thin’, landed just short of the green, bounced and rolled to four feet; and a putt sank ‘with the same pleasure I would have sunk a glass of ice-cold beer right then’. Subtle differences maybe, but any golfer will be able to spot the proud flourishes a mile off. Still, a par is a par. A hole had gone by, and Maurice hadn’t dropped a shot!

Yet, it was too little too late. Maurice might have made his first professional par at the 14th, but the enormity of that effort, and the realisation that, despite the achievement, he was still 38 shots over the norm, took the wind from his sails. That total became an even uglier 43-over after he took nine at the 15th. He contemplated walking off the course. ‘There was a moment when I wished I was miles away, but that passed. What was I doing thinking such thoughts? I had every intention of completing the round, no matter what, and if I kept trying, who knows? I might still strike some sort of form and salvage something from the wreckage!’

RELATED: Best Golf Clubs for Beginners

Many lesser men would have taken the easy option of quitting by posting a ‘no return’, but Maurice struggled on. He made subtle adjustments to his grip and major ones to his swing, hoping to achieve even a small semblance of form. But he had run out of ideas, and there was nothing left in the tank. It was not to be.

After over four hours of struggle against the elements and his own ability, Maurice G Flitcroft, virgin professional golfer, staggered over the line. He’d been a dead man swinging over the last three holes, completing his card with a miserable 5-7-5, coming back, exhausted, in 60 strokes, for a round of 121.

A sizeable crowd had gathered in front of the clubhouse. Smiling, applauding and cheering, they welcomed the returning non-conquering hero. ‘My instinct and reason told me why they were there,’ said Flitcroft. ‘They were there not so much to greet us, and give a round of applause, but to satisfy their curiosity, see with their own eyes this golfing phenomenon.’

Howard sent his caddie into the clubhouse to get some drinks for everyone. Instead of waiting under the beating sun for the thirst-quenchers to turn up, he strode off to the recorder’s tent. His playing partner Dave Roberts was already inside it, and in deep conversation with an official, who by now had worked out the man he thought had a back problem on the 1st tee early in the morning had suffered an altogether different kind of breakdown.

The official was called Sands Johnson, and his job was to check all cards as they came in and record the scores. Howard joined in the discussion. Neither player was particularly happy; Roberts had shot 82, Howard 86. Both men were fully expecting to shoot scores in the mid-to-low 70s, and both were certain of the reason they hadn’t hit their mark. They were upset and wanted to speak to an official. When asked why they said: ‘Just look at the scorecard!’ Not only did Maurice G Flitcroft (unattached)’s card have a three-figure score scrawled across the bottom of it, next to the 7th hole was the figure ‘12’ and a massive question mark.

‘I had to query it,’ says Johnson. ‘Both of them stood there and said, “Well, that’s when we lost count.” So they were obviously sick to death about what had happened. And not too happy with Mr Flitcroft. My initial problem was with the question mark, but the fact it was 121 didn’t help matters. I was in doubt as to whether it was the correct score. Looking back, chances are it wasn’t. But they’d obviously got sick of Flitcroft by the time they’d got to the 7th hole.’

The man himself had yet to make his presence felt in the recorder’s tent. He was still outside, having waited patiently for Roberts’ caddy to return with the drinks. With shades of Ice Cold in Alex, this golfing John Mills slaked his thirst – no doubt imagining he was back on the 14th green, plucking his par putt from the hole. The crowd buzzing around him, Flitcroft – momentarily disorientated – considered his next move.

He was snapped out of his reverie by an R&A official, who according to Maurice, bore ‘a resemblance to John Cleese’. The official certainly shared Cleese’s authoritarian shtick, ordering the supine ‘golfer’ into the recorder’s tent. Budging not an inch, and performing mathematical gymnastics in his head, Maurice worked out that he would probably have to shoot a round of 23 the following day to qualify for the Open proper – in other words, he would have to record a minimum of 13 holes-in-one!

READ NEXT: The Phantom of The Open reviewed

-

Maurice Flitcroft looks at the Claret Jug.

Maurice Flitcroft looks at the Claret Jug.

-

Maurice Flitcroft at home with his golf clubs.

Maurice Flitcroft at home with his golf clubs.

-

Maurice Flitcroft at home.

Maurice Flitcroft at home.

-

Maurice Flitcroft at home.

Maurice Flitcroft at home.

-

Mark Rylance plays Maurice Flitcroft in The Phantom of The Open.

Mark Rylance plays Maurice Flitcroft in The Phantom of The Open.

-

Mark Rylance plays Maurice Flitcroft in The Phantom of The Open.

Mark Rylance plays Maurice Flitcroft in The Phantom of The Open.

-

Rhys Ifans plays Keith MacKenzie, Flitcroft's nemesis from the R&A, in the film.

Rhys Ifans plays Keith MacKenzie, Flitcroft's nemesis from the R&A, in the film.

-

Maurice Flitcroft, played by Mark Rylance in The Phantom of The Open, drew a band of supporters.

Maurice Flitcroft, played by Mark Rylance in The Phantom of The Open, drew a band of supporters.

-

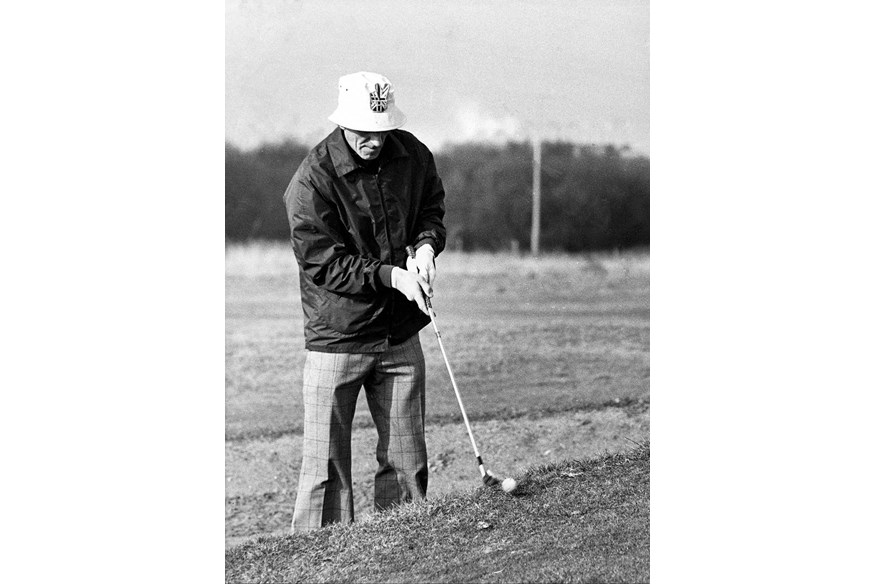

Maurice Flitcroft on the golf course.

Maurice Flitcroft on the golf course.

-

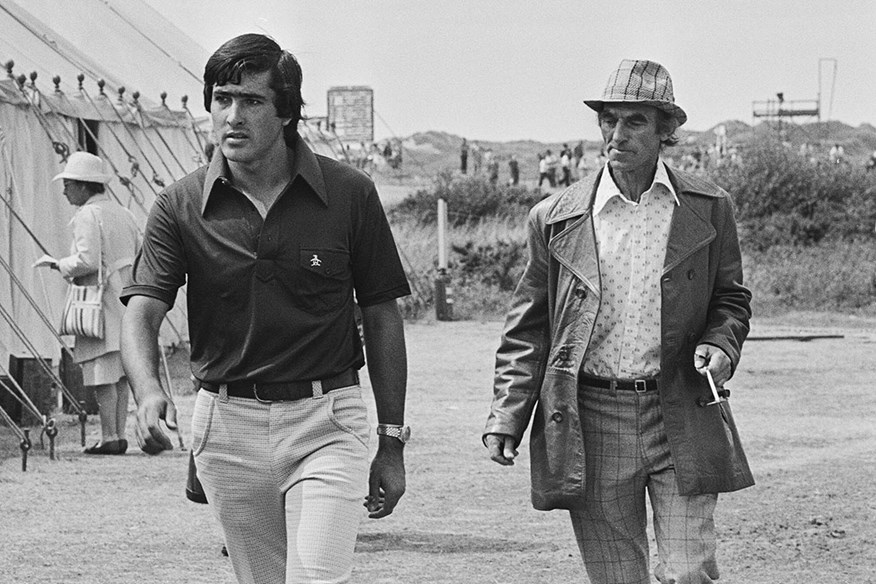

Maurice Flitcroft follows Seve Ballesteros at The Open.

Maurice Flitcroft follows Seve Ballesteros at The Open.

-

Mark Rylance (centre), plays Maurice Flitcroft in The Phantom of The Open, which was written by Simon Farnaby (left), and directed by Craig Roberts (right).

Mark Rylance (centre), plays Maurice Flitcroft in The Phantom of The Open, which was written by Simon Farnaby (left), and directed by Craig Roberts (right).

-

The Phantom of The Open tells the incredible story of Maurice Flitcroft.

The Phantom of The Open tells the incredible story of Maurice Flitcroft.