Tiger Woods’ racism and bigotry battle

Last updated:

As Tiger Woods is inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame, we look back at how racism and bigotry cast a shadow over the teenage life of the world’s most famous golfer.

This story is taken from the October 2007 issue of Golf World magazine but, after Tiger Woods’ speech as he entered the World Golf Hall of Fame, we believe this story is more relevant now than ever.

The legend of Tiger Woods seems destined to end in triumph, when he one day overcomes Jack Nicklaus’ record of 18 Major victories. But when the glorious history is finally written of how the son of Earl and Tida Woods conquered the golfing world, it will take a detour along a suburban street in Cypress, a suburb of Los Angeles in southern California. It will tell the story of how racism and bigotry cast a shadow on the life of the teenager who was destined to become the greatest player the game has ever seen.

RELATED: The 100 Most Influential People In Golf

The story begins on a road that leads visitors past a fading ‘Authorised Personnel Only’ sign and into the car park at the Navy Golf Club, a course owned by the US military. It was here, a few hundred yards from Woods’ boyhood home, that he, his father Earl and his father’s friends would meet up every Saturday morning for their weekly game of golf. And it was here the boy genius developed his skills – despite the efforts of people who were determined to make his early golfing life as miserable as possible.

RELATED: How Tiger dominated the Official World Rankings

“It was only a small group, but they were in a position of power at the golf club. They had the choice to make life easy for Tiger or make life difficult. They chose the latter path,” says Joe Grohman, who was an assistant professional at Navy in the early 1990s.

“Part of the problem was some of the members didn’t want a young kid running around the place, but it was also because of the colour of his skin. There weren’t that many black families in Cypress at that time, remember,” says Scott von Eps, who worked in the pro shop.

“I used to think they treated him badly because they were idiots, but the more I think about it, they were probably racists, too,” says Roger Wells, who was one of the Saturday morning gang.

Not that you will hear any of these complaints from Woods himself. The world’s most famous athlete is also the world’s most reticent athlete when it comes to his personal life, and for a long time the Saturday morning gang was happy to follow his lead. But the death last year of Earl, who was held in the greatest respect by his friends, and the return of Grohman to Navy Golf Club as the head professional, has seen embarrassed silence turned into humble and public apology.

“It’s just a dark stain on the history of this place that I want to go away,” he says. “We want Tiger to know that we are sorry, that we love him and want him to come home.”

Grohman’s plea for forgiveness is especially poignant because, once upon a time, he was great friends with the Woods family. “I knew Earl before I knew Tiger. He was a great player and practised all the time. The golf course was never busy, so me and Earl would talk for hours in the pro shop,” he recalls.

“One day I saw Earl teaching this little kid out on the range. He would say something and the kid would just swing, and then Earl would say something else. The kid wasn’t even acknowledging Earl. This was making me mad, so I went up there and said, ‘Listen young man, you better listen to Earl here because he knows what he is talking about’. And Earl bursts out laughing. ‘Joe,’ he said, ‘don’t you know my son, Tiger?’ After that me and Tiger were great buddies.”

The pair played their first game of golf together a few days later, and like everyone else who had seen the young Tiger Woods play, Grohman could scarcely believe that someone so young could be so good. “But that impressed me most of all was his attitude and his respect for the game. On the first four greens I couldn’t see his pitch marks, but on the fifth I saw him pull out a dinner fork and fix his mark. Man, I thought that was so cool.”

There were a few years of an age difference between Grohman and the young Woods, but they spent a lot of time together, playing golf – or at least a few holes of golf – virtually every day. Away from the course, they hung out as well. Grohman has a box of memories from those days – old photographs, his invitation to Tiger’s high school graduation, a couple of old junior competition trophies won by Tiger – that would sell for a fortune on eBay, but which he would never dream of selling.

“This stuff belongs to Tiger and I would just love him to drive into that car park out there and come in and pick them up,” he says.

The chances of that happening are not good. Woods is a world-class bearer of grudges against those whom he believes have done him wrong. There is no doubt he was badly treated by some people at Navy Club. But if he has a long memory for those who did him wrong, there must be hope he will also remember those who described him as a special talent.

Bob Rogers, a retired army officer who was a close friend of Woods Snr, played with Tiger almost every weekend from when the youngster joined the club, aged 10, until he went to college seven years later. He recalls a respectful, polite kid who was mature beyond his years and could hold his own with the older men when it came to trash talking and, of course, when it came to golf.

Rogers was both a witness to Earl Woods’ unique brand of coaching and a willing sacrifie to its effectiveness. “One day I said to Tiger, ‘I’m going to match you shot for shot today’. I parred the first hole and Tiger birdied it, and as we headed towards the next tee he walked past me. He didn’t even lift his head, but I heard this little voice say, ‘You’re one down’.

“That was Tiger. He was such a competitive kid. I went home that day and I told me wife I had played golf with a kid who could become one of the all-time greats,” he laughs. “I tell people that I used to kick Tiger Woods’ butt… until he turned 12.”

RELATED: What’s in Tiger Woods’ golf bag

He was not alone. All of the Saturday morning crowd took a beating at the hands of Woods, but still they jostled to get into his fourball.

“I had played with some guys who ended up on the Tour, so I knew what a good played looked like and, believe me, this kid looked the part,” says Roger Wells. “I remember once, when he was about 11, he was whining about not being able to hit the ball as far as we could and, at the same time, two or three of us turned round and said, ‘F*** you, Tiger. Pretty soon you’ll be smacking it way past us.”

At 13, Woods got his handicap down to scratch. At 14, he won his fifth World Junior Championship and a year later became the youngest winner in the history of the US Junior Amateur Championship – impressive landmarks on the steady march to golfing greatness, all the more so because he achieved them against a backdrop of almost daily harassment from a group of club members and employees who seemingly hated having him around the place.

Just why this was so is a matter of debate between those who were there at the time. “They treated everyone badly, these people. It was that old thing – put someone in a uniform and give them a little bit of power and they turn into A-holes,” says Wells.

Bob Rogers believes that some people in positions of authority at the golf club picked on Tiger because they didn’t like his father. “Personally, I found Earl to be a great griend; generous, with a big heart. But there’s no doubt some people had no time for Earl because they thought he was pompous or something.”

Woods Snr had endured racism when he was growing up in 1950s America. He was a talented baseball player who was good enough to play for his college team in Kansas, yet when he travelled with his team-mates he was often forced to stay in different hotels because some hotel owners had a whites only policy.

It was the same story in the US Marines, where he reached the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. By day, white subordinates would salute him. After work he would be forced to sit at the back of the bus on the way home while his white subordinates sat in the whites only section at the front.

“Growing up the way he did, Earl experienced a lot of things, and he would have experienced things at the golf club that someone like me – a white guy – would never have noticed. Yet he never said a word about racism,” recalls Rogers. Even so, he was still a victim of it. Earl’s friend at the time remembers a couple of incidents where he was rebuked by former staff at the golf club for no other reason than the colour of his skin.

Tiger’s problems were more actute and more widely talked about. “There were people at the club who were always worried he was getting something for nothing,” recalls von Eps. “If I was working in the shop, they would come and ask me if Tiger had paid for this or that. Tiger never expected anything for free but, if I had anything to do with it, he was getting as much as I could give him. If he bought a $5 range token, I was giving him $15 worth of balls.

RELATED: How Tiger Woods changed the game of golf

“It was the same with golf carts. If Tiger came out to the course in the afternoon to practise and then play a few holes, I’d just give him a golf cart and let him go off on the golf course. He didn’t pay for the cart – if he wasn’t using it, it would just have been sitting there.

“One day, one of the club’s volunteers came in and said they saw Tiger on one of the fairways with a golf cart, hitting half a dozen shots to the green and asked if I knew this wasn’t allowed. The problem with guys like that was they didn’t understand what it took to be a great golfer – Tiger had probably hit a bad shot and dropped a few balls to get it right. Big deal.”

Von Eps’ only concern was that Woods would fulfil his potential. “Tiger was the best golfer of his age in history – I wanted him to have endless practice, as much as he could swallow. Do you think all those country club kids he was playing against in the national championships around the country were sweating over the price of a bucket of range balls, or whether or not they could take a golf cart and go off and hit a few balls from the middle of the fairway? I don’t think so.”

Pettiness was heaped upon pettiness. After he won his first US Junior Amateur Championship, Tida Woods, Tiger’s mother, brought a tray of Asian food over to an empty clubhouse for a small celebration party, but was turned away. The rule, even for national champions, was that all food eaten on the premises had to be purchased there.

One summer, Woods got a letter from the club informing him that he had to carry a receipt with him at all times for the use of range balls and golf carts because there “had been complaints from club members”.

“I know for a fact that no one else in the club ever got a letter like that,” says Grohman. “Tiger showed it to me and asked, ‘Why are they doing this, Joe?’. I didn’t know what to tell him. I knew for a fact that there had been no complaints from any members. The problem was with one guy in management who just didn’t want Tiger around the place. In the end I tried my best to protect him from a lot of the stuff by not telling him what was going on.”

Alas, his best wasn’t quite good enough. Shortly after he won the US Amateur Championship, Woods was approached on the driving range by a then club employee who, according to numerous sources, told him he would have to leave because there had been a complaint about a “nigger” hitting balls on the range. “There was no way Tiger was hitting balls into anyone’s back garden,” says Rogers. “He wasn’t a bad enough golfer.”

Grohman was working in the club shop when he found out what had happened. “I ran over to their house. Tiger had already told Earl, so when I walked into the front room it was like walking into a funeral,” he recalls.

“I said I knew a three-general, an African-American, and I could tell him what was going on. Earl said he didn’t want to drag a general into the whole thing and Tiger felt the same. ‘That’s just the way it is, Joe,’ he said.”

This was always Woods’ response, and when he wasn’t brushing aside the indignities, he was trying to build bridges.

One day Grohman idly mentioned to his young friend that he was embarrassed at the poor quality of the trophies he was forced to give out to the club’s junior members. That afternoon Tida Woods called and said her son had suggested to her he donate his trophies to the club for the use of the junior section. “She turned up the next day with 297 trophies,” Grohman recalls. “Can you think of a 50 year old who would want to part with his trophies, never mind a 15 year old?”

But gestures like that did nothing to thaw the chill. Roger Wells recalls a television crew coming to the club to film a story with Woods.

“They had all their equipment on a golf cart, which they had then parked on the driving range. That was against the rules, so of course they made a big deal out of that and made them take the cart off the range,” he says. “You would think a golf club like the Navy would have been delighted to get TV coverage, wouldn’t you?”

Wells argues the club didn’t realise, or didn’t want to acknowledge, it had a genius in its midst. “They really should have said to him, ‘Tiger, you are really special and we are going to make all kinds of exceptions to the rules for you because you are so special’.

“Instead, they went out of their way to make sure he didn’t get any special treatment. In fact, they went to the extreme on the other side – they treated him worse than everybody else.”

When Woods won the US Amateur Championship for the first time he offered to display the trophy in the Navy clubhouse. The offer was never acknowledged. “They just ignored him when they should have been proud to house the US Amateur trophy, especially with all the names it had on it, like Bobby Jones and Jack Nicklaus,” says Rogers. “They should have rolled out the red carpet for the kid, but instead they slammed the door in his face.”

In all, Tiger Woods won the US Amateur Championship three times. The trophy, meanwhile, ended up on display at Big Canyon Country Club, a high-end golf course in nearby Newport Beach. The management there heard about the young golfer’s problems at Navy and offered him an honorary membership.

Woods, whose family would never have been able to afford the joining fee for a place like Big Canyon, accepted. He returned to Navy for the occasional practice session late in the evening, but when he left for Stanford University the ties were cut for good.

Twelve years later, the Navy course has a brand new clubhouse and, it seems, a new attitude. Gregg Smith, a US Navy spokesman, concedes that the young Tiger Woods was treated badly by some of the people who used to work there, but that their behaviour in no way reflected the attitudes of the US military.

“Those who may have been involved in what happened back then were mostly retired military people. And with certain people like that, their views of society were formed 20 or 30 years earlier. It was as if they had travelled ahead in a time machine,” says Smith.

But if military officials are quick to acknowledge that the young Woods was mistreated at Navy Club, they have been slow to acknowledge that he spent his formative years as a golfer playing on their golf course.

For years, visitors would never have known the most famous player on the planet had spent his early years at Navy Golf Club. There were photographs of other golfers on the clubhouse walls – of Arnold Palmer and David Toms. But not Tiger.

“Some golf clubs might want to make a big deal out of the Tiger Woods connection for commercial reasons, but at Navy we don’t feel the need to do that,” says Smith.

“The golf club is owned by the US military and, as such, does not face the same commercial pressures as other clubs. It’s not that we are ignoring Tiger’s links, it’s just that we have had so many other things going on in recent years. We have just completed a new clubhouse, so maybe we can put something in there to mark the connection.”

The sooner the better, argues Grohman, who intends to put his collection of Tiger Woods memorabilia to good use.

“I’m planning to build a little shrine in the clubhouse to the memories of the old days. But only the good memories,” he says.

“The other stuff is so ugly that I’ve never wanted to talk about it before. But I realise now some good can come out of it, especially if kids in the inner cities are able to see what Tiger was able to overcome. And if it helps him to realise that he can come home any time he wants, then that’s great, too.”

READ NEXT: What would Tiger Woods’ handicap be?

-

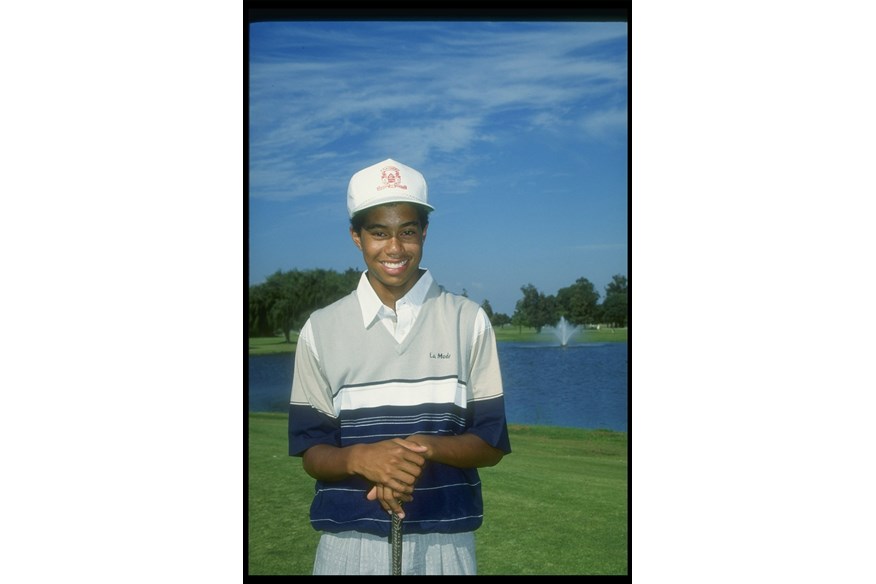

Tiger Woods experienced racism at his first golf club.

Tiger Woods experienced racism at his first golf club.

-

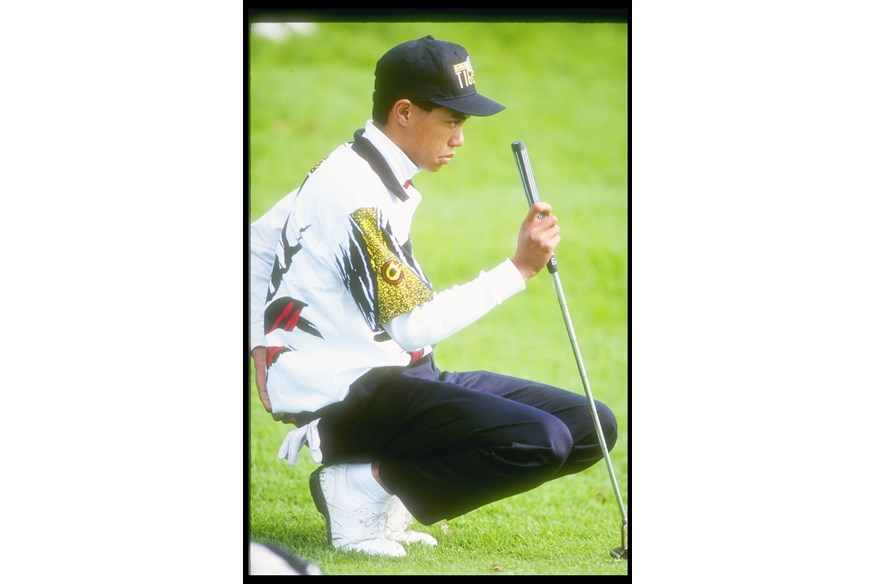

Tiger practises alongside father Earl.

Tiger practises alongside father Earl.

-

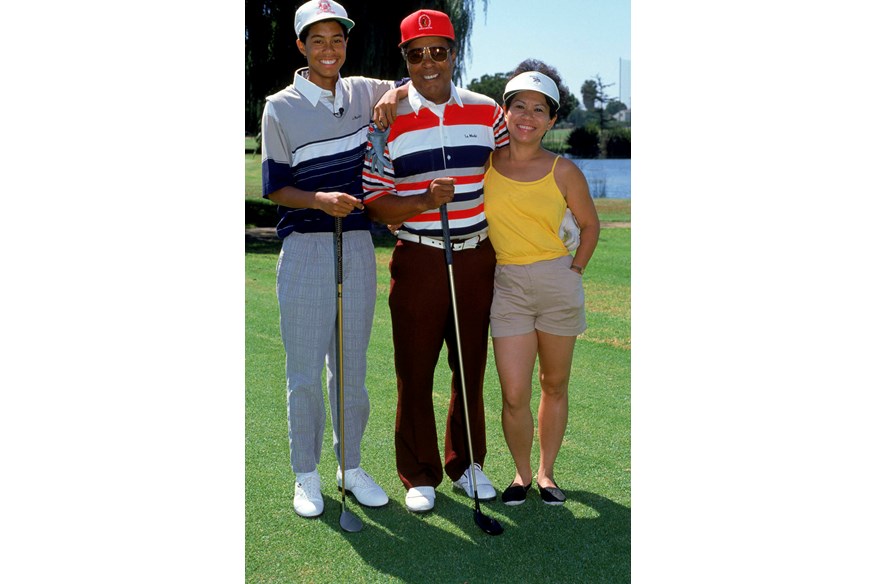

Tiger Woods, pictured with his family, was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Tiger Woods, pictured with his family, was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame.

-

Most golf clubs would have been proud to have Tiger Woods, but not Navy GC

Most golf clubs would have been proud to have Tiger Woods, but not Navy GC

-

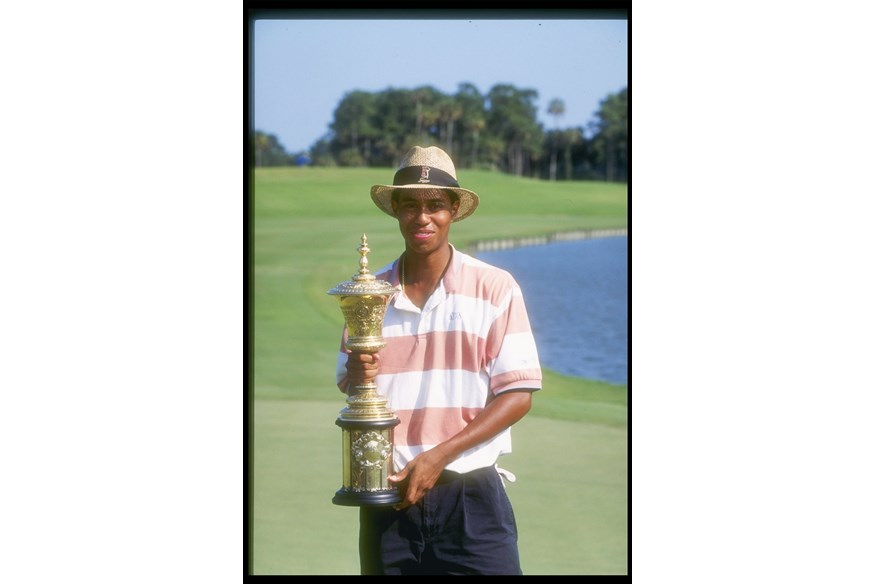

Tiger Woods' amateur success wasn't always enjoyed at Navy Golf Club

Tiger Woods' amateur success wasn't always enjoyed at Navy Golf Club

-

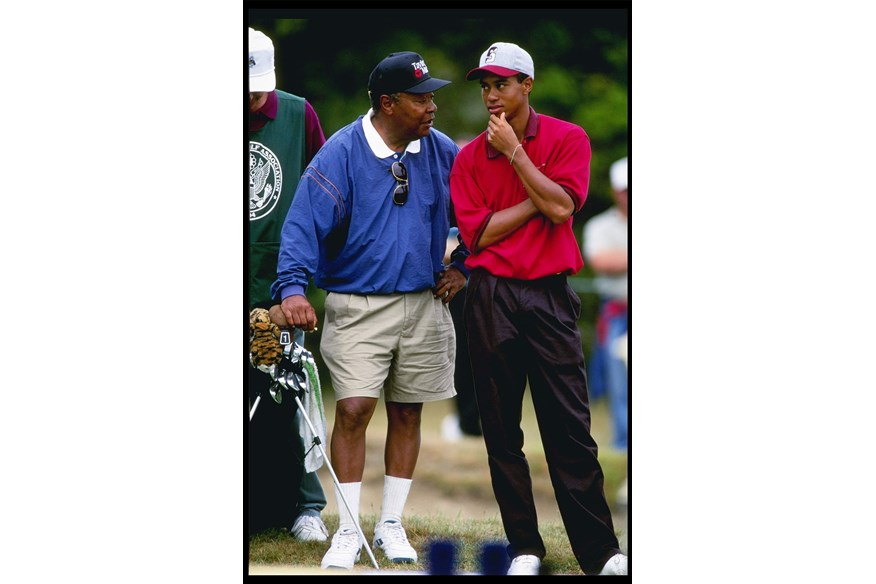

Tiger Woods and father Earl had a very close relationship.

Tiger Woods and father Earl had a very close relationship.

-

A young Tiger Woods with parents Earl and Tida.

A young Tiger Woods with parents Earl and Tida.

-

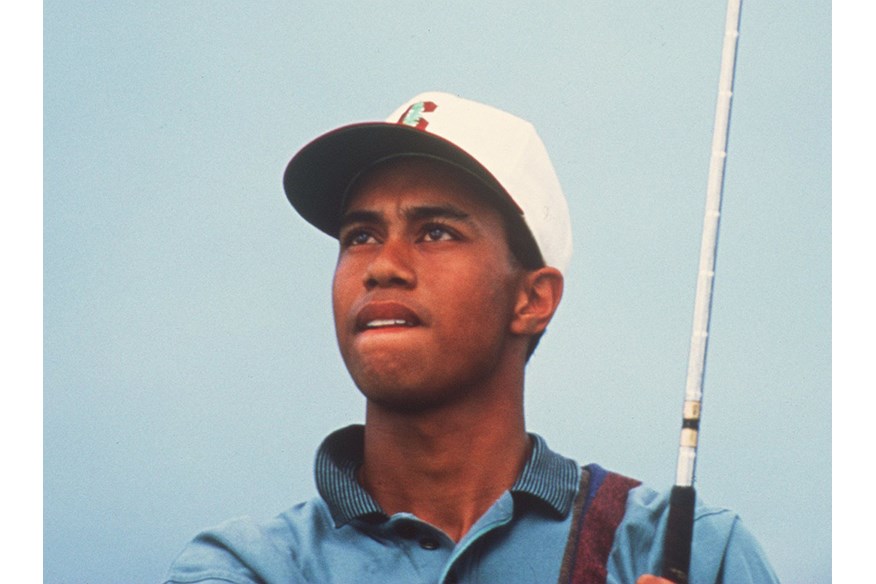

Tiger Woods was destined to become the greatest golfer on the planet.

Tiger Woods was destined to become the greatest golfer on the planet.

-

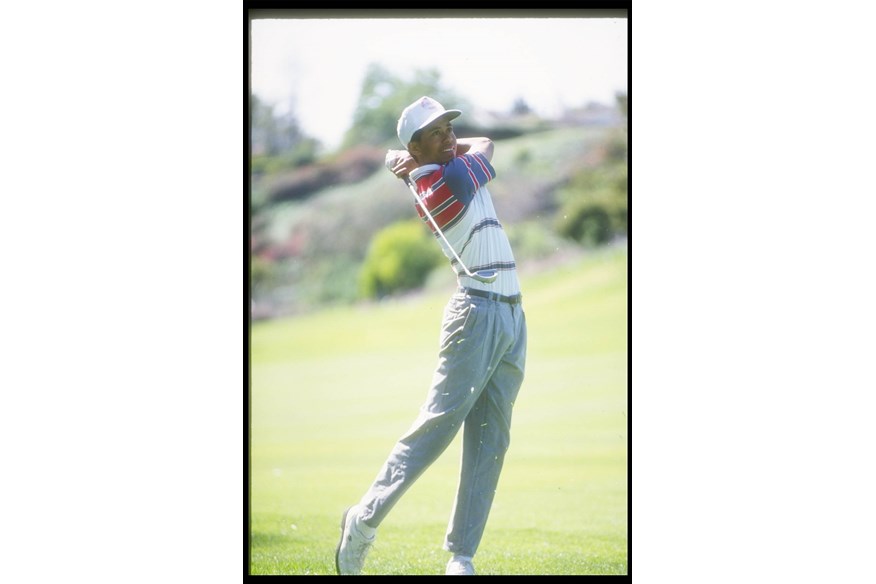

Tiger Woods has represented the USA many times.

Tiger Woods has represented the USA many times.

-

A young and explosive Tiger Woods led to golf courses lengthening to combat his distance

A young and explosive Tiger Woods led to golf courses lengthening to combat his distance

-

Tiger Woods wasn't always welcome at his first golf club.

Tiger Woods wasn't always welcome at his first golf club.

-

A young Tiger Woods had incredible golfing ability.

A young Tiger Woods had incredible golfing ability.