Pete Cowen: The key to a consistent short game

Last updated:

Pete Cowen, the coach of U.S Open champion Gary Woodland and PGA Champ Brooks Koepka, has built a career out of turning golfers into serial winners. Now it’s your turn…

Pete Cowen has had plenty to celebrate this year: Being the short-game coach of Brooks Koepka will do that, having picked up his fourth major and posting two runner-ups at the Masters and U.S. Open. But he is also the coach of first-time major winner Gary Woodland, totalling two majors for 2019 alone. We met up with him at the end of last year to get his insight in to how he can help your game…

What Pete Cowen doesn’t know about the golf swing isn’t worth knowing. Ask him a question and the response will arrive in double-quick time, guaranteed to elicit that ‘a-ha’ moment. Ask him to name every pro he’s currently working with, however, and his reply might take a little longer.

He settles on 14, but struggles to remember all of them. At Le Golf National, he coached Brooks Koepka, Ian Poulter and Henrik Stenson, but over the past three decades he’s mentored all but four of this year’s European Ryder Cup team. The captains and vice captains included. His business model is such that he never goes in search of finding players; the reality is they find him.

Cowen’s open-door policy on tour and at his three academies – one in Rotherham, two in Dubai – applies to all but a select few who have burned bridges, left him and tried to come back. They include a former world No.1 and a European Tour Rookie of the Year. That ruthlessness underpins his coaching philosophy, and was evident when he gave Koepka an ear-bashing at Erin Hills in 2017.

“He didn’t thank me for it at the time,” says Cowen, but he did when he left as US Open champion. Another two Majors followed in 2018 to take Cowen’s tally to five in three years, and a further two so far in 2019.

The running joke on tour is that Cowen practically lives on the range, but it’s not far from the truth. At the WGCHSBC Champions, he was the first on the range and the last off it. He reckons he clocks up 250,000 air miles a year, and only gets paid a percentage of a player’s winnings, depending on their results. It does mean he can go weeks, months even, without earning a penny in return, but having Koepka on his books means that’s rarely the case. They started working together five years ago, just after Koepka won his European Tour card. Since then, they’ve celebrated three Major titles together.

The biggest improvement has been Koepka’s short game, something he openly credits Cowen for. The man himself is more matter of fact, claiming that the American’s short game has gone from two out of 10 to four out of 10.

“That’s a 100 per cent improvement right there,” he adds.

Every golfer would settle for that, we tell him, but it doesn’t take long to realise that your typical club golfer has more in common with the world No.1 than you might think… (jump to drills)

Pete Cowen on short game…

I think a lot of players – tour pros included – fail to understand the technique behind a chip, pitch or bunker shot.

A great bunker player can spin it left to right, right to left, or flight it high or flight it low, just by applying different pressures into the sand. It’s the same with chipping, and being able to understand how you make the motion simpler by using the loft and bounce. I had to educate Brooks Koepka about that.

Most club golfers, because they are taught to keep the hands ahead through impact, don’t understand how to engage the bounce, either.

If you have 15 degrees of bounce but you lean the shaft, laterally, 16 degrees, the bounce is now -1 degrees. So, then they start sticking the leading edge into the turf, and fat it an awful lot. That comes from not getting the bottom of the arc correct, and trying to force the ball towards the target, rather than allowing the club to return to its natural position.

At the Ryder Cup, I spent a lot of time helping Brooks and Rory in the bunker.

I was actually Irish coach when Rory was 14 so I knew his bunker play from back then and he had lost it a bit. We went back to basics and that sorted it. I set up a station and made sure the mechanics were good. Players tend to forget what made them good, and often it all comes back to the basics.

When I’m on the range with a player, I might set them a challenge of hitting nine shots: A low fade, low draw, low straight, mid fade, mid draw, mid straight, high fade, high draw and high straight.

The challenge is to do them in the correct rotation. If they fail, they’ve got to start again. That’s a consequence drill. With the short game, sometimes I set a station up where they’ve got to pitch five balls to a flag. I then ask them how close they expect to hit each ball. So, if it’s a simple chip, they might say, ‘every shot within three foot.’ So, three times five is 15. Their challenge is to get all five balls inside a total distance of 15 foot, otherwise they start again.

Graeme McDowell does the par-18 drill a lot.

Kenny, his caddie, will put him in difficult positions around the green and set him the challenge of getting up and down with at least one of two balls. Any kind of consequence drill is great to replicate the pressure of competition.

I’ve had over 250 wins in the last 23 years, and ten Major wins.

All the time people come up to me, asking for help. Just recently, I helped Pep Angles in Portugal. He was struggling with his game, hadn’t made a cut in ages and then he finished 12th. Most of the time I just make them understand what they should be doing. That’s half the battle. I’m not reinventing the wheel. I see a lot of players trying to relearn the golf swing, instead of trying to do the correct thing, better.

I always say, don’t swing to stay in balance, swing in balance.

If you watch someone who hits it down the middle all the time, they swing within themselves, finish perfectly in balance and can hold that position for 20 seconds. Most golfers can’t do that because their mechanics aren’t good enough.

The swing is like a spiral movement.

If you want to create a little torque in the body, which is where the power comes from, you need to do more than just turn the shoulders. You need to use your lower body and feel like you’re turning a screw with your feet so you can wind up into the backswing. As you swing back, the weight should move like a spiral, from the left foot to the right ankle, left ankle to right shin, left shin to right knee, left knee to right thigh and left thigh to right hip. When you go from left hip to right ab, you can then start to match the positions with the hands. By that I mean when you go from left ab to right chest, your hands are at chest height. When you go from left chest to right shoulder, your hands are at shoulder height. Thinking like this will get the body working properly and create a set of reference points for different lengths of shots. It’s much easier than consciously putting your hands at nine o’clock, 10 o’clock or 11 o’clock.

Ninety per cent of players would be better playing with their feet together.

Why? Because they will turn around a more consistent centre, and so the bottom of the arc will be more consistent as well. Plus, they will only lose 10 per cent of their usual distance. Research has proved that.

You can save yourself a lot of shots if you keep things simple.

I will give you an example. When I was watching Vijay Singh at the Masters a long time ago, he was right of the green on the 15th and playing a flop to a pin just over the bunker. In the practice round, he was landing it right by the flag, no problem at all. But in the tournament, he chose to chip it to the back of the green. He didn’t even try the shot, despite the fact he had been practising it. He knew he could get himself into a lot more trouble by trying something so risky. At worst he was going to make par. A lot of the time it’s about playing the percentages.

If you want to play a release chip, use a 7-iron.

If you want a slightly flighted chip, use a 9-iron. If you want a high chip, use a lob wedge. But regardless of the club change, stick to a vertical set up. That’s why a lot of pros stand with their feet close together when they’re chipping, so they can keep the centre of the sternum over the ball a lot easier.

There’s a lot of confusion about hinging and cocking, especially when it concerns shorter shots.

You cock the wrist up and down, and hinge the wrist back and forward. You need to hinge when you chip, and then use a combination of the two when you’re pitching. If you try and cock the wrists like a hammer when you chip, that’s what throws the club miles out of plane and adds unwanted height. If you keep the shaft more vertical and have a slight hinge, the action almost resembles a brushing motion which gets the ball running on the ground a lot quicker.

If you are chipping as opposed to pitching, the goal should always be to get the ball running on the ground, as quickly as you can.

When I helped Brooks at the US Open at Pinehurst, we were talking a lot about chipping because there were so many run offs. I put him in six different spots and said ‘if your life depended on it, what shot would you play?’ He said ‘if my life depended on it, I would putt!’ He finished fourth that week and got his Tour card. Martin Kaymer won and he’s not a great chipper. What did he do? He putted most of the time. Everybody thinks that they need to chip when they’re off the green, but the short game is about getting the ball in the hole. Sometimes, we force ourselves to chip and ignore the simplest shot. I’ve seen Phil Mickelson chip so many times when he should be putting.

One of the biggest faults I see is people standing too far away from the ball, and having little control of the butt end of the club.

If the butt travels too far back or forward when chipping and pitching, it causes the bottom of the arc to change which causes inconsistencies. The more you minimise the movement, the better your consistency will be.

If you watched Todd Hamilton win the 2004 Open, you might remember that he used a hybrid almost like a chipper.

In many ways, he was eliminating two shots. When you chip with a rescue club, the thickness of the sole can almost bounce through the grass, which eliminates the fat shot. Plus, because it’s hard to get underneath the ball on a links course, it’s easy to thin a chip with a wedge. That’s why golfers who suffer from the yips, or play a lot of links golf, could benefit from using a rescue club and playing it like a putt. The little bit of loft on the face will get the ball up and over a patch of grass, and running on the ground a lot quicker.

I wouldn’t recommend playing a flop shot unless the lie is near perfect.

You need grass underneath the ball, but most people attempt it when the lie is bare. Mickelson can get away with it because he has no bounce on some of his wedges. But the timing still has to be perfect, and a lot of the time people don’t swing back far enough and then decelerate into impact. They’re scared basically, and if you’ve got no confidence, your short game will suffer.

One shot I think people should practise more is the ‘belly wedge’.

When the grass is up against the ball, trying to play a normal chip or even a flop shot is almost impossible because there’s usually so much grass between the ball and club that it just doesn’t come out. When you don’t have any control, sometimes you just need to get the ball tumbling forward, even if it doesn’t look pretty. Using your lob wedge and trying to thin it with the leading edge to cut through the grass and hit the back of the ball is far more effective.

PETE COWEN: DRILLS

Build your bunker station

Seve was the first guy to show everybody on tour how to hit a bunker shot properly, so that when it hits the green it rolls out like a putt. He would stand square to the target and release the club into the sand, rather than cutting across it. If you stand wide open and swing across the line of your feet, you’ll create an awful lot of side spin and have a long and thin divot. The ideal bunker divot should be oval, like a dinner plate. This is how you do it…

People always say how difficult the 40-yard bunker shot is, but that’s because people undercut the sand and fail to generate the speed and pressure to get it that distance. They then try and hit it harder, take too much sand and lose balance.

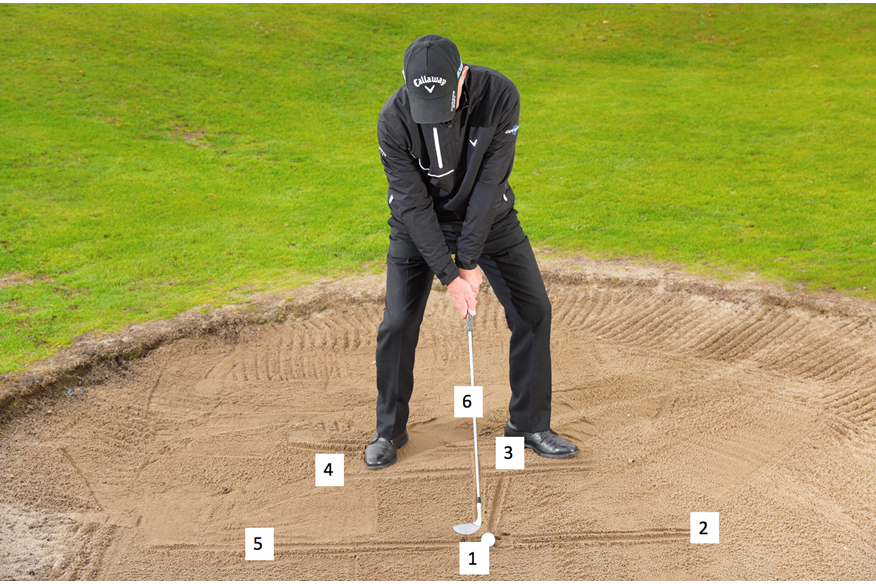

When practising, draw lines in the sand to give you a series of reference points. Start by sketching a box in the sand, two inches in diameter around the ball

(1). Next, create a right angle by drawing a target line

(2) and a ball-position line

(3). Take your stance accordingly, with your left heel resting on the ball-position line. Keeping your left knee over your toe, flare the foot out at a 60-degree angle and then draw a toe line

(4) so it points slightly left of the target line. From here, draw a swing line

(5) so it simulates a slightly outto- in path and overlaps your target line. As you take your set up again, draw a final line

(6) to create a right angle from the centre of your toe line. This acts as an important visual tool for the position of your shaft and the centre of your sternum at address.

All that’s left to do is swing back, follow the swing path line and splash the face into the box

(1). Just make sure you keep the club travelling through the sand to engage the bounce and keep the loft on the face.

The basic chipping technique

Every single golfer who is bad at chipping should try this technique. Graeme McDowell and Brooks set up like this, and it’s a foolproof way to achieve a better strike. To start with, grip down the handle – almost to the steel – and stand so the clubhead sits almost vertical at address and the arms hang naturally. Don’t worry about the heel being off the ground. The swing isn’t going quick enough for the lie angle to influence the strike. From here, slightly hinge the wrists as you take the club back and then let gravity and the weight of the club take over to return the club to its original position.

As long as you don’t push forward with the hands into impact, the butt should move only fractionally, which will ensure the bottom of the arc stays consistent.

TRY THIS: How you position your sternum in relation to the ball is key. The centre of your chest should neither be behind or in front of the ball. If I want to hit it high, I might move the ball position forward in my stance and just back of centre to hit it low. All the while my sternum is staying over the ball. That way the strike pattern is the same every time.