TPC Sawgrass: From a swamp to a spectacle

Last updated:

TPC Sawgrass today is a picture-perfect spectacle. But the land upon which The Players’ Championship course stands was originally far from ideal for golf.

TPC Sawgrass, the host of The Players Championship, is now considered one of the best golf courses in the USA, but it took a lot of work for it to achieve that status.

Immediately following the 1983 Players Championship – the second year the PGA Tour’s flagship event had been staged at its brand new TPC of Sawgrass Stadium Course in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida – the famed golf course architect Pete Dye received a brusque call from the then PGA Tour commissioner Deane Beman.

“I’ve got a near mutiny on my hands, Pete,” Beman barked into the phone. “You have to get back down here and make some changes to the golf course.”

A few days later, Dye and his right-hand man Bobby Weed, now a very successful architect in his own right, stood on the 1st tee surrounded by 10 disgruntled tour professionals. The freshly assembled ‘design committee’ included the likes of Jack Nicklaus, Ben Crenshaw and Hale Irwin.

Over the next few hours, the group walked the entire golf course. Weed took notes as the players vented their frustrations and unleashed their opinions on the Stadium Course’s design. “It turned into an 18-hole grill and roast of Pete Dye,” Weed recalls. “But in my entire career, I’ve never seen anybody conduct themselves on a more professional level than Pete that day. It was excruciatingly difficult, but Pete was polite and gracious throughout.”

No aspect of the Stadium Course layout was spared the players’ vitriol. They didn’t care for the straight lines off the tees because they didn’t have reference points in the fairways to aim at. They didn’t care for the angular nature of the holes or the steep runoffs around the greens that they claimed made the players look foolish when chipping. They disliked also the penal pot bunkers, the tight landing areas and the unkempt areas just off the fairways. But it was the greens complexes that raised their hackles the most, however.

Intentionally designed with four distinct quadrants to accommodate a different Thursday through Sunday pin position, each zone housed an almost spirit-level flat putting surface. Tour players prefer a slightly breaking putt to a dead straight one, but the real problem was that the quadrants were separated by mammoth undulations, prompting Jack Nicklaus to state, “I’ve never been good at stopping a 5-iron on the hood of a Volkswagen.”

“The greens were radical and ahead of their time,” admits Weed. “And as the speeds went up and the grass was cut shorter, it got even worse. They became a massive issue. In 1982 and ’83, TPC Sawgrass was a very unpredictable golf course. Over the next five years, we made a lot of changes. Many were justified, but some I regret to this day.”

To understand how the PGA Tour came to host its flagship tournament on such a controversial golf course, we have to consider the commercial context of its creation. When Deane Beman was appointed commissioner in 1974 – just six years after the PGA Tour had cut ties with the PGA of America – one of his first tasks was to negotiate a new TV deal.

While players like Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player were international stars who commanded big-money endorsements, the PGA Tour itself was spluttering. The annual total purse was less than $8 million and the schedule was a mishmash of events, several of which were underwritten by celebrities such as Bob Hope, Dean Martin, Andy Williams and Bing Crosby. “A couple of big-name players and a hotdog stand at the turn,” was tour player turned TV commentator Peter Jacobsen’s succinct description of the situation at the time.

To compound matters, golf’s four flagship events, the Masters, US Open, Open and US PGA, were owned and controlled – as they still are – by other organisations. Tennis was the hottest property in sport in the US at the time, while golf, in terms of TV exposure at least, ranked way down the popularity list. It even lagged behind such small-time sports as ten-pin bowling. In short, Beman had very little leverage. “We were a minor sport with major stars,” he stated.

To survive and grow, the PGA Tour needed to identify new revenue streams. In the 1970s, the major TV networks covered only a handful of golf events outside of the major championships due to the high production costs. One of Beman’s early big decisions was to replace the celebrity hosts with mainstream sponsors.

Although seen as controversial at the time, the cash injection from Corporate America boosted tournament purses and enabled the Tour to offer the networks’ pre-sold sponsor advertising packages that helped underwrite their production costs. The initiative paved the way for future year-round TV coverage of key events.

An even riskier gambit saw the Tour venture into staging its own tournaments. In 1974, the very first Tournament Players Championship was played at Atlanta Country Club in Georgia. The following year, the event moved to Colonial CC in Texas then onto Inverrary GC in south Florida before finding a temporary home for a few seasons at the windswept Sawgrass Country Club, near Jacksonville.

Several years later, Beman would further bolster the Tour’s schedule by transforming the World Series of Golf from a small four-player exhibition into a full-field international event, collaborate with Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer to launch The Memorial and Bay Hill Invitational tournaments, and create the Tour Championship – a big-money, end-of-season shootout for the top 30 players on the official Money List. “I was quite certain,” Beman said, “that the Tour had to have its own events to compete for the sports and entertainment dollar.”

RELATED: Best Golf Courses in the World

The idea that just wouldn’t go away

A decade or so earlier, when he was still playing on Tour, Beman had approached the United States Golf Association (USGA) with the idea of developing a portfolio of purpose-built, spectator-friendly golf courses that could host US Opens and other USGA-owned events, as well as double up as state-of-the-art turf science facilities.

Although the USGA elected not to pursue his proposal, the idea lingered at the back of Beman’s mind. It resurfaced during the 1975 Phoenix Open when, as the newly appointed PGA Tour commissioner, he decided to take a closer look at the fan experience. “I had to buy a periscope to see anything. No wonder we didn’t have huge galleries,” Beman said. “It became apparent that trying to compete with other sports at stadiums where fans are seeing the action in one place was a real challenge. If you walk four or five miles, you ought to be able to see what you want to see.”

Beman’s vision for the new iteration of the Tournament Players Championship was multifaceted. First, the event would need to deliver an enhanced viewing experience closer to the action. Second, it had to showcase the Tour’s best-in-class tournament-hosting capabilities. Finally, to avoid sharing revenues with third-party course owners, the event would need to be owned 100 per cent outright by the PGA Tour. To achieve all three objectives, there was only one solution. The PGA Tour would have to build or acquire its own golf course.

Since the PGA Tour didn’t have the money to fund a completely new development, the first step was to approach the owners of the current host, Sawgrass CC, with an offer to purchase the club and the land. However, the chairman of the Arvida Corporation, Charles Cobb, not only refused to sell, he bet Beman $100 he would never obtain the financing to buy the facility he needed to achieve his dream.

A win-win deal that changed everything

Just across the street from Sawgrass CC, however, was a 5,300-acre stretch of wooded wetlands owned by local property developers Jerome and Paul Fletcher. At the time, the brothers were slightly behind on their mortgage payments on the property and were being ‘encouraged’ by their bank to strengthen their collateral. Recognising that the construction of a world-class golf course would drive further leisure development in the area and, in turn, significantly increase property values in the long run, the Fletchers agreed to sell a 417-acre parcel of land to the PGA Tour for just $1. It was a classic win-win.

Sourcing the land and ironing out the financial logistics were only half the battle, though. At a policy meeting in 1978, the PGA Tour’s board agreed to fully support Beman’s initiative on the condition that the majority of the players were also on board. Gaining consensus proved easier said than done. Many of the players, including Nicklaus and Palmer, struggled to see any commercial value in the Tour owning and operating golf courses. “There were not a lot of people who were real supportive when we started,” Beman stated in an interview. “Our top players were more interested in themselves than they were in the organisation and advancing the game.”

Beman used every trick in the book to garner support from the players. He went out on Tour for eight weeks, during which time he would set meetings at inconvenient times – very early in the morning and during pro-ams – to ensure as few people as possible showed up. “I didn’t want more than five or six players at any one meeting,” Beman admitted in an interview with Golf Magazine. Beman’s final ploy was to place a notice on the bulletin board, then approach the dozen or so players he knew would be supportive and have them sign in the ‘yes’ column. The rest of the players quickly fell into line and the vote passed 100-4.

Reluctant to commit any of the PGA Tour’s own money to his pet project for political reasons, Beman ventured into the local business community for financial support. Memberships were sold to 50 investors at $20,000 apiece to contribute to the start-up costs, while bank financing covered the remaining $5 million in construction expenses for the golf course and clubhouse. “Not one nickel of the Tour’s money was spent here,” Beman told Sports Illustrated in a 2004 interview. Pete Dye, the designer of Beman’s favourite tournament course, Harbor Town in South Carolina, was hired to build the Stadium Course. Dye’s brief was simple: create a spectacular golf course with equally balanced nines and finish with three exciting risk-reward holes to encourage the pros to play aggressively.

The transition from boggy wetlands to a championship-calibre layout wasn’t seamless, however. On his first visit to Sawgrass, Dye was taken out to inspect the only dry part of the property. He would later continue his assessment of the rest of the site alone… in a rowing boat!

The land the PGA Tour acquired for its single dollar investment has often been referred to as a swamp but, alligators and all manner of dangerous creatures aside, the terrain was actually several feet above sea level and would comfortably have been able to dry out if the construction of the adjacent Highway A1A hadn’t blocked all of the natural drainage routes. “It was a man-made bog,” Weed says. “If you look close enough today, you’ll still see a lot of big oak tree snags burned black. If it dried out and a fire started from a lightning strike, it would just burn.”

For the first six months, Dye and Weed focused their efforts on building an 18,000-foot canal around the perimeter to drain the property. In doing so, they were able to install a pump and lower the water table. “When we first arrived, the water level was at the same elevation as the ground in some areas,” Weed says. “But we could pump out up to 60,000 gallons of water per minute and that allowed us to control the water level. That control was put to the test a couple of times in 1983 and 1984 when we had massive rainfall before and during the tournament.”

After the excess water was channelled away, the next step in bringing Beman’s vision of a spectator-friendly course to life was lowering the fairways. The excavated material – largely decaying organic matter – was piled high, then covered in grass and sand to create the large viewing mounds alongside the fairways. The steepest mounding was placed to the right side of fairways so that spectators would be able to see the players hit shots without looking at their backs. “Frankly, stadium golf evolved as much because of the bad material we had to get rid of as anything else,” Weed says.

RELATED: Best Golf Resorts in the World

Rattlesnakes, gators and machetes!

Throughout his career, Dye often stated that Sawgrass was one of the most challenging and, at times, precarious sites he was ever given to manage. Encounters with venomous water moccasins and rattlesnakes occurred on an almost daily basis, while it was not unusual for workers to find themselves wading through bog water armed with a machete to clear the thick Palmetto swamp grass and ward off unwelcome advances from the wildlife.

It didn’t help the stress levels that Dye’s firm was often juggling multiple projects. At one point, Dye and his construction team were staying at a condo in Hilton Head, South Carolina, while they worked on Long Cove GC.

“One night, I remember Pete coming back to the house at 1am, having driven two-and-a-half hours up from Ponte Vedra Beach,” Weed says. “He would take off his old muddy shoes and I would hear him walking up the steps. Then at 5.30am, he was beating on my bedroom door, saying, ‘Get up. You can’t build a damn golf course lying in bed!’

Eventually, the project took its toll. On one occasion, Pete came in and said, ‘I just don’t know if we can finish this course down in Ponte Vedra. I just don’t know if we can turn a swamp into a golf course. It may not have been meant to be built on that site’.”

One of the biggest construction challenges was sourcing the sand needed to provide the course’s foundations. The budget didn’t stretch to purchasing the material, so the design team had to go looking for it on the property. Eventually, they discovered a large seam adjacent to the 16th green. “When we found it, we went as deep as we could until it ran out,” Weed says. “That’s why the lakes between the 9th and 18th, and the one around 17 are as big as they are. It’s where we found the most sand.”

But solving one problem created another. By the time the construction team had exhausted the sand supply next to the 16th green, there was a huge pit where the par-3 17th hole was supposed to be. In Dye’s original plans, the hole was to play alongside a relatively small lake, but that was no longer possible. The problem perplexed Dye until his wife, Alice, suggested that they simply fill the pit with water and create an island green. Dye agreed… reluctantly.

The Stadium Course’s eye-catching features actually disguised a very low budget construction. The original greens were built using native soil, while single-row fairway irrigation meant that areas of arid ground lurked on the peripheries of the course. A flock of goats were brought into control weed growth. They were kept on the property until, one day, they learned to climb up a berm onto the clubhouse roof.

Four years after first breaking ground, Beman and Dye unveiled their creation to the world at the 1982 Tournament Players Championship. The stadium aspects were immediately well-received, but the extreme design irked many of the players.

Many, many changes would be made to the course over many years. Dye and Weed softened the contours of the greens. They widened several fairways. They eliminated a hungry pot bunker in front of the 18th green. They installed marker mounds to give golfers something to aim at from the tees.

“There’s no doubt that the initial design was compromised, but all courses evolve,” Weed says. “Pete and I would laughingly say that we should have 90 holes here because we’ve changed the design so much over the years, but I think it has constantly been shaped and moulded into a better course. I have some significant reservations and regrets about what I had to do to make some changes, but at the end of the day it’s a far superior golf course in every respect.”

THE STORY BEHIND SAWGRASS’ ISLAND GREEN

How TPC Sawgrass’ iconic par-3 17th hole really came to fruition

The generally accepted story of how TPC Sawgrass’ famous 17th hole was conceived is that Alice Dye, the wife of architect Pete Dye and an accomplished golfer in her own right, came up with the idea of creating an island green after visiting the site at the end of the first day’s construction.

While that is true, Dye had originally planned for the hole to play alongside a very small lake. It is common practice in Florida for architects to dig out sand on the property to create mounding and other course features. The deep, empty pits later become lakes and water hazards in a practice known as “cut and fill”.

The area adjoining the 16th hole was simply that. Dye had dug a huge hole to create quality landfill for the rest of the golf course and had little idea as to how he was going to finish the 17th hole.

Alice suggested he leave the pit as a lake and simply insert an island green right in the middle of it. The rest, as they say, is history.

RELATED: Why are some green fees so high?

STRENGTH, STRATEGY, SURPRISE

Pete Dye’s former right-hand man, Bobby Weed, explains what makes the Stadium Course such a great all-round test of golf

Physical and mental challenge

“Great golf courses equally test a player’s physical and mental agility. Many tour pros these days say they don’t care where the ball goes off the tee as long as it’s way out there. Well, here it matters. You can easily get into a position where your approach shot becomes extremely difficult.

“Getting up-and-down, even more so. If you can get a tour player putting his hand on several different clubs on the tee, you’ve mentally engaged him. Whatever selection he makes, if he doesn’t pull the shot off, he’ll have to put it behind him and move on.”

Perfect balance

“You can’t predict the winner very easily at Sawgrass because the course has great balance and doesn’t favour a one-shape hitter or a bomber. Overall, it has as many left-to-right holes as right-to-left.

“In several cases, you have both on the same hole. For example, the first hole calls for a fade off the tee and a draw into the green. If you’ve only got one shot shape in your armoury, you’ll get exposed here eventually.”

Hazards, hazards everywhere!

“While modern tour players can find a way to shoot lights out on any course these days, including TPC Sawgrass, you can put a ball in a penalty area on damn near every hole. Hazards lurk everywhere.

“Here, you’ll often hear players say, ‘That was a really good bogey’ because it could have been a lot worse. Although we have greatly softened the perimeter of the golf course over the years, you can still get yourself in trouble pretty quickly.”

Optical illusions

“Nobody really understands that the spectator mounds were positioned only to the sides of fairways for a reason. With the exception of the 4th hole, you won’t see any of those mounds behind the greens.

“Pete only wanted native and natural vegetation beyond the greens in order to make depth perception more difficult. As architects, we only have a few tools at our disposal to create illusions that can make the top players think twice. Messing with their depth perception is one of them.”

The Tough Holes

“Pete always had a very strong belief that if you want to toughen up a golf course, you go find the hardest holes on the golf course and you make them even harder. That’s how you strengthen any golf course. At Sawgrass, for example, you wouldn’t go to the short par-4 6th and add length because it’s a short hole to begin with.”

An incredible closing stretch

“People always talk about the famous trio of closing holes at Sawgrass, but the stretch from 14 onwards – with the exception of 16 – is an incredible run in because it’s full of risk/reward. I discount 16 because of its shortness as a par 5.

“One of our deep regrets is redesigning that green. The original green complex there would rival anything in the world. Although we need a little more length on 15 these days, it’s a left-to-right tee shot and a right-to-left shot into the green.

“And 14 was a great hole from the very outset because it was right-to-left off the tee and right-to-left into the green as well. I remember playing the course before it opened and hitting 3-iron in there. The next thing you know, Fred Couples is hitting 8-iron in. I think we’ve backed the tee up on 14 three times now.”

READ NEXT

– The Top 100 Golf Holes

-

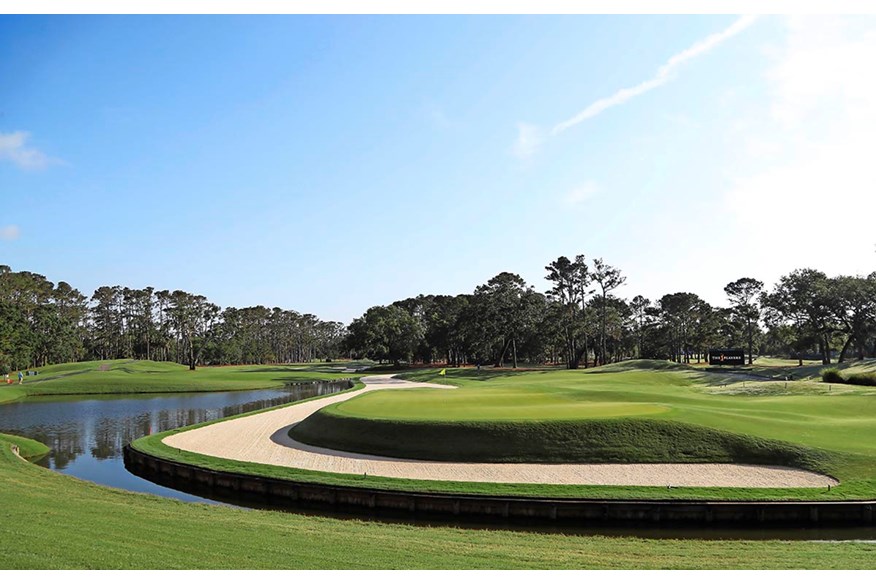

The famous par-3 17th at TPC Sawgrass.

The famous par-3 17th at TPC Sawgrass.

-

In Dye’s original sketches, the 17th hole was a longer short hole that played alongside a small lake.

In Dye’s original sketches, the 17th hole was a longer short hole that played alongside a small lake.

-

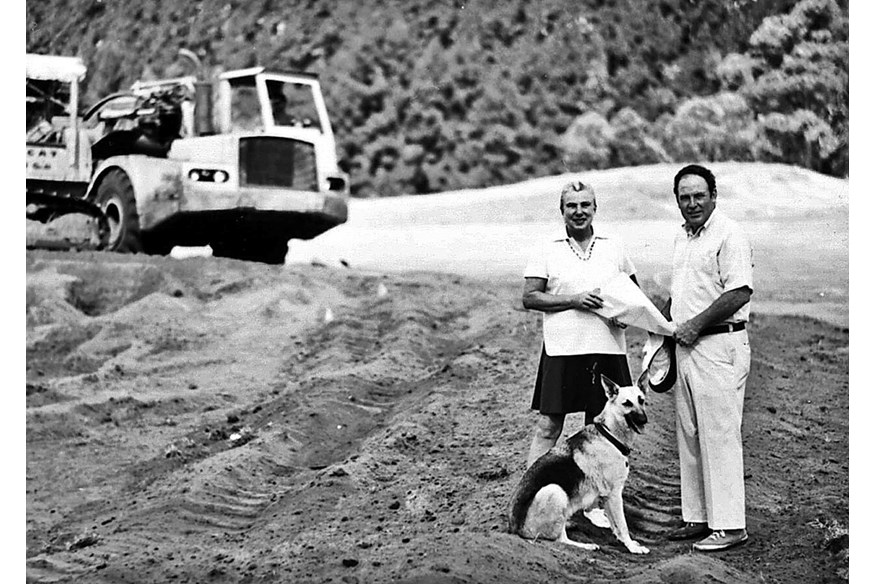

Pete and Alice Dye look over the plans on the Sawgrass site.

Pete and Alice Dye look over the plans on the Sawgrass site.

-

The 11th hole at TPC Sawgrass.

The 11th hole at TPC Sawgrass.

-

Pete Dye oversaw big changes to the 12th at Sawgrass in 2016.

Pete Dye oversaw big changes to the 12th at Sawgrass in 2016.

-

The 13th hole emerges from between the Sawgrass oaks.

The 13th hole emerges from between the Sawgrass oaks.

-

An early view from behind the 13th green.

An early view from behind the 13th green.

-

The 16th at TPC Sawgrass.

The 16th at TPC Sawgrass.

-

The par-5 16th from the back tees, the lake now greatly enlarged.

The par-5 16th from the back tees, the lake now greatly enlarged.

-

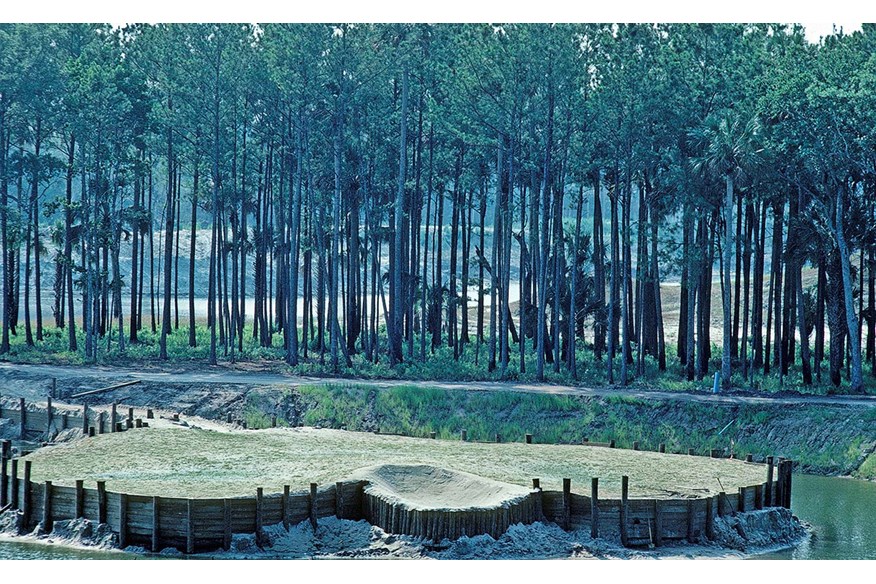

Water begins to fill the pit surrounding the 17th green.

Water begins to fill the pit surrounding the 17th green.

-

The 18th tee shot at TPC Sawgrass.

The 18th tee shot at TPC Sawgrass.

-

The stadium-style seating was placed to the sides of the tees and fairways, but never directly behind the greens.

The stadium-style seating was placed to the sides of the tees and fairways, but never directly behind the greens.

-

An alternative view of the first tee and stadium-style seating.

An alternative view of the first tee and stadium-style seating.

-

The 9th and 18th holes during construction in the late 1970s.

The 9th and 18th holes during construction in the late 1970s.

-

The 17th at TPC Sawgrass has become an iconic hole.

The 17th at TPC Sawgrass has become an iconic hole.

-

Still flanked by dry ground, the 17th hole begins to take recognisable shape.

Still flanked by dry ground, the 17th hole begins to take recognisable shape.